The good thing about being a libertarian is that real-world events repeatedly demonstrate that your skepticism of big government is fully justified.

- Nations that adopt dirigiste policies don’t do well.

- States that adopt dirigiste policies don’t do well.

- Localities that adopt dirigiste policies don’t do well.

The bad thing about being a libertarian is that there are very few governments that even partially follow laissez-faire policies.

In Asia, we have Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

In Asia, we have Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.- In Africa, we have Botswana.

- In Europe, we have Switzerland.

- In Latin America, we have Chile.

Moreover, there’s always a risk that those few governments with reasonably good policy will veer in the wrong direction.

I worry that’s happening in Hong Kong, and I fear it may happen today in Chile if voters make the wrong choice in a national referendum.

In a column for Quillette, Axel Kaiser from Chile’s Adolfo Ibaniez University analyzes what is happening.

In an extraordinary development, Chileans are deciding whether they want to create an entirely new constitution from scratch or preserve the existing one. …Chileans will also vote on whether the new constitution will be drafted by a mixed constitutional convention of politicians and elected representatives from the citizenry, or a constitutional assembly composed entirely of citizens. In either case, decisions by the body would require a two-thirds majority, and its deliberations must be completed within a year.

…the new process portends a period of political instability, and the specter of open-ended conflicts and stand-offs between different branches of government. …To many outside Chile, it may seem strange that what has been arguably the most stable and prosperous country in Latin America would circumvent its institutions in this way… But in fact, the creation of an entirely new constitutional order has long been an ambition of the Chilean Left. …Revolutionary efforts to upend existing constitutional schemes have been a common feature in Latin America since the 19th century. …The idea that a new constitution will provide Chile with an instant solution…various forms of social conflict has become an attractive delusion. Yet the more likely scenario is that it will simply legally encode the unrealistic ideological demands that brought Chile to this point in the first place. ……many voters seem…swayed by extravagant promises of the future benefits they will enjoy under a new (and as yet undrafted) constitution. …56 percent of Chileans believe that a new constitution would lead to higher pensions, better education, and superior health care, among a long list of other improvements.

And he also explains why voters should be big fans of the current constitution.

At least if they care about good results, especially for those with lower incomes.

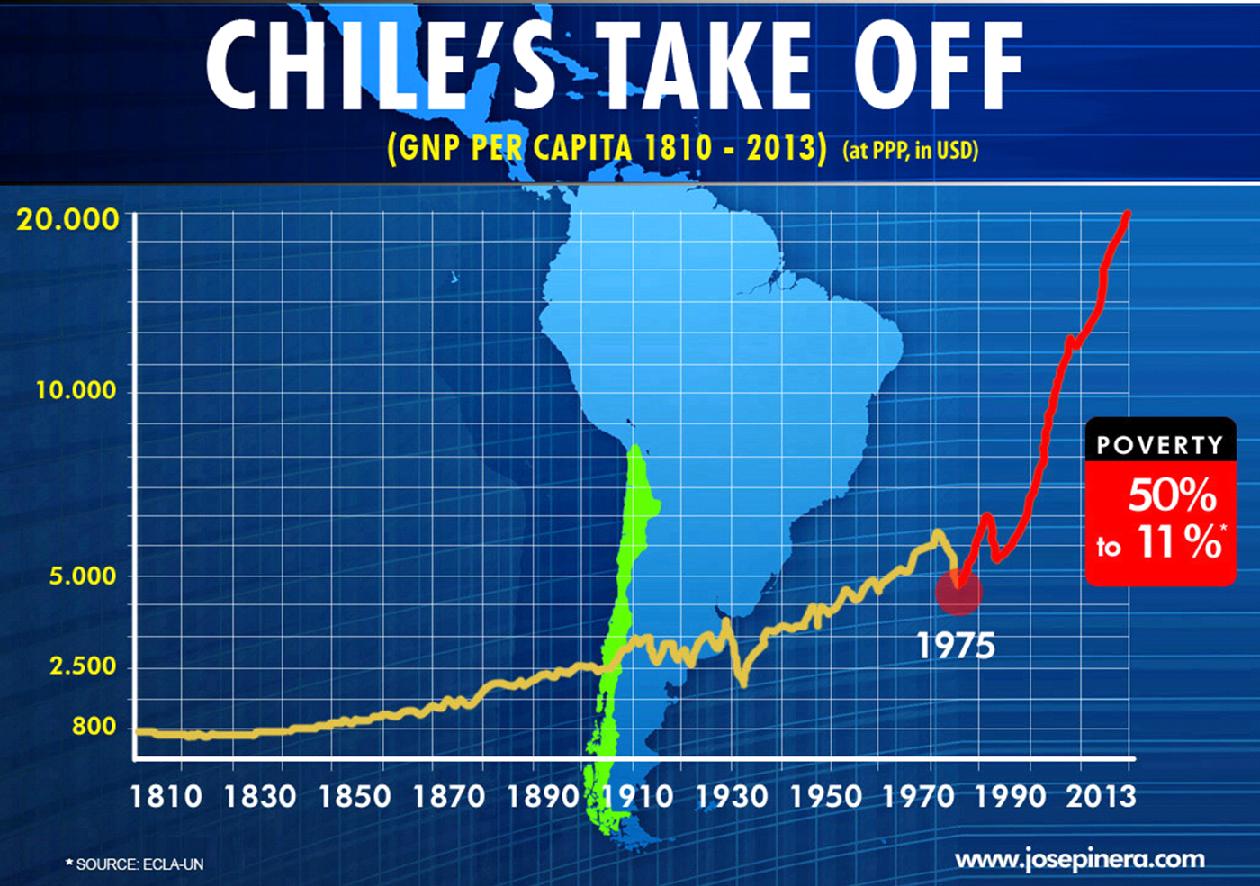

Under the period covered by the current constitution, inflation—which had peaked at over 500 percent in 1973—fell below five percent by the 2000s. Between 1980 and 2015, per-capita income in Chile quadrupled to $23,000—the highest growth rate in Latin America. More importantly, life expectancy rose from 69 to 79, and levels of housing overcrowding fell to one-quarter of its pre-1980 levels. The middle class, as that category is defined by the World Bank, grew from 24 percent of the population in 1990 to 64 percent in 2015. Extreme poverty fell from 34 percent to less than three percent. Between 1990 and 2015, the income of the richest 10th of the population grew a total of 30 percent, while the income of the poorest 10th saw an increase of 145 percent. The Gini index, a widely used statistic that measures income inequality, fell from 52 in 1990 to about 48 in 2015. Chile also held the highest position among Latin American nations in the 2019 UN Human Development Index.

Mary Anastasia O’Grady, in her Wall Street Journal column, is concerned that Chileans may be poised to make a big mistake.

Chile is on the cusp of collective political and economic suicide… On Oct. 25 Chileans will vote on whether the country needs a new constitution. Polls indicate that the “yes” vote will prevail even as the process of rewriting the highest law in the land is shaping up to be a disaster.A new constitution is likely to put at risk

the model of democratic capitalism that brought Chilean poverty to below 10% in 2018, from nearly 70% in 1990. Chile also had the highest social mobility in a 2018 Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development study of 16 member countries. …Many Chileans seem to believe that a new constitution will make things right, à la Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela circa early 2000s. …Referendum backers say it is a “democratic” process. It is certainly majoritarian. But Chileans are bound to be disappointed if higher living standards and greater opportunity are the goal. The nation will be lucky if it finishes the exercise on par with the impoverished Argentine welfare state. …expect a document that reads like a litany of unattainable aspirations.

Some people favor majoritarianism, of course, especially if the result is a new set of “positive rights” to other people’s money.

In a column for the New York Times, Professor Michael Albertus hopes a new constitution will incorporate statist economic policy.

Chileans will vote to reject or approve the start of creating a new constitution. The citizens of more countries should do the same. The country’s current Constitution…has protected conservative interests and the military and has suppressed political dissent for 40 years.

…The vote to convene a constitutional assembly in Chile could lead to a new document that brings the leadership closer to the people… It could also enshrine greater rights for labor unions, establish health care and education as fundamental rights… Most of Chile’s protesters and their supporters are largely motivated by bread and butter issues like higher pay, gender equity, improved health care access and quality medical care, pension reform, more rights for Indigenous peoples, access to affordable public transportation and free public education. …Protesters view a new constitution as key to delivering on these demands.

So why might Chileans be willing to gamble with their nation’s prosperity?

Early this year, Axel Kaiser offered some insight in a column in the Wall Street Journal.

He blames a left-leaning former government for creating economic malaise.

The economic pain started with the antimarket reforms of the previous government under Socialist President Michelle Bachelet, from 2014-18. Ms. Bachelet increased corporate taxes by 30%; signed a law banning the replacement of workers on strike,

thereby dramatically increasing the costs of labor; increased public spending at three times the economic growth rate; and unleashed armies of regulatory bureaucrats on the private sector. Capital investment fell in each year of her term. Such a consistent reduction in investment hasn’t happened since data was first collected, in the 1960s. Economic growth collapsed from an annual average of 5.3% under the previous government of Mr. Piñera (2010-14) to 1.7% under Ms. Bachelet. Real wage growth took a 50% hit.

By the way, I take no pleasure in having predicted that Ms. Bachelet’s tenure would yield bad results.

But let’s not focus on her mistakes.

Indeed, Mr. Kaiser thinks her bad policies (and the anemic Bush/Macri/Sarkozy-type approach of the current government) are largely a reflection of a bigger problem.

The policies result from a profoundly false narrative Chilean elites tell themselves about the country. Over the past 20 years, intellectuals, media personalities, business leaders, politicians and celebrities in this Latin American nation have marketed the myth that Chile is an extreme case of injustice and abuse. It began at the universities, where progressive ideologues spread the idea that there was nothing to feel proud about when it came to Chile’s social and economic record. …Ms. Bachelet’s second term and her social justice-driven agenda were the inevitable result. …The free market didn’t fail Chile… The central problem is that a large proportion of the elites who run key institutions—especially the media, the National Congress and the judiciary—no longer believe in the principles that made the country successful. The result is a full-blown economic and political crisis. Other nations should take note: This is what elite self-hatred can do for you.

I wonder if Alex is referring to the United States when warning other nations about the danger of “elite self-hatred.”

It’s certainly true that many elites in America are quite disdainful of the nation’s economic system. Which has always mystified me since that system enabled their success – or the success of their parents, which allows them to lead very comfortable (albeit guilt-ridden) lives.

More important, it enabled ever-higher living standards for ordinary people, which should please folks on the left, at least if we believe their rhetoric (though I fear many of them are more motivated by hostility to the rich rather than love for the poor).

But let’s not digress. I want to close by noting that poor people have been the biggest winners from Chile’s free-market reforms.

This tweet from Professor Daniel Lacalle is a perfect example. It shows how poverty has plummeted, regardless of which measure is used.

The bottom line is that lower-income people have enjoyed the biggest income gains. And that bit of data is especially impressive given how fast income has grown for the entire country.

P.S. I’ve already written that the most important referendum for 2020 is the upcoming vote whether to retain the Illinois flat tax. Perhaps I should have listed today’s vote in Chile?

———

Image credit: Mark Scott Johnson | CC BY 2.0.