I’m not a big fan of bureaucracy, mostly because government employees are overpaid and they often work for departments and agencies that shouldn’t exist.

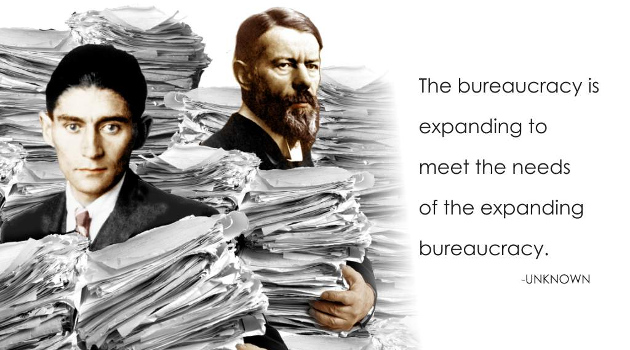

Today, motivated by “public choice” insights about self-interested behavior, I want to make an important point about how bureaucracies operate.

We’ll review two articles about completely disconnected issues. But they both make the same point about ever-expanding bureaucracy.

First, the Economist has an article about central banks, specifically looking at how they employ thousands of bureaucrats. What makes the numbers so remarkable, at least in most of Europe, is that they no longer have currencies to manage.

Central bankers around the world have long pondered why productivity growth is slowing. …But might central banks themselves, with their armies of employees, be part of the problem? …many central banks in Europe look flabby. Although the euro area’s 19 national central banks have ceded

many of their monetary-policymaking responsibilities to the European Central Bank (ECB)—they no longer set monetary policy by themselves, for instance—they still retain thousands of employees… the Banque de France and the Bundesbank each employ more than 10,000 people… The Bank of Italy employs 6,700. All told, the ECB and the euro zone’s national central banks boast a headcount of nearly 50,000. …The Board of Governors in Washington, DC, where most policy decisions are made, had about 3,000 staff at last count. When the Fed’s 12 regional reserve banks are included, the number rises to more than 20,000.

I actually wrote about this issue back in 2009 and mentioned the still-relevant caveat that some central banks have roles beyond monetary policy, such as bank supervision.

That being said, this chart suggests that there’s plenty of fat to cut.

What I would like to see is a comparison of staffing levels for countries that use the euro, both before and after they outsourced monetary policy the European Central Bank.

I would be shocked if there was a decline in the number of bureaucrats, even though monetary policy presumably is the primary reason central banks exist.

By the way, there’s a sentence in the article that cries out for correction.

Although central banks have become more important since the global financial crisis, it is not clear why they need quite so many regional staff.

It would be far more accurate if the sentence was modified to read: “…have become more of a threat to macroeconomic stability since the global financial crisis that they helped to create.”

But I’m digressing.

Let’s now look at the next article about bureaucracy.

John Lehman, a former Secretary of the Navy, recently opined in the Wall Street Journal about bureaucratic bloat at the National Security Council.

The problems that plague the NSC trace to before its founding in 1947. The White House has long sought to centralize decision-making to overcome the political jockeying that often takes place within the national-security establishment. …The NSC was established in the 1947 National Security Act,

which named the members of the council: president, vice president and secretaries of state and defense. …under President Nixon…, Mr. Kissinger grew the council to include one deputy, 32 policy professionals and 60 administrators. …the NSC has only continued to expand. By the end of the Obama administration, 34 policy professionals supported by 60 administrators had exploded to three deputies, more than 400 policy professionals and 1,300 administrators. The council lost the ability to make fast decisions informed by the best intelligence. The NSC became one more layer in the wedding cake of government agencies.

Wow.

A bureaucracy that didn’t exist until 1947 and didn’t even have a boss until 1953 then grows to almost 100 people about 20 years later.

And then 1700 bureaucrats by the Obama Administration.

Needless to say, I’m sure that the growth of the NSC bureaucracy wasn’t accompanied by staffing reductions at the Department of State, Department of Defense, or any other related box on the ever-expanding federal flowchart.

Whenever I read stories like the two cited above, I can’t help but remember what Mark Steyn wrote almost ten years ago.

London administered the vast sprawling fractious tribal dump of Sudan with about 200 British civil servants for what, with hindsight,

was the least-worst two-thirds of a century in that country’s existence. These days I doubt 200 civil servants would be enough for the average branch office of the Federal Department of Community Organizer Grant Applications. Abroad as at home, the United States urgently needs to start learning how to do more with less.

As always, Steyn is very clever. But there’s a very serious underlying point. Is there any evidence that additional bureaucracy has produced better decision making?

Either in the field of central banking, national security, or in any other area where more and more bureaucrats exercise more and more control over our lives?

Maybe there is such evidence, but I haven’t seen it. Instead, I see research showing how bureaucracy stifles growth, creates waste, promotes inefficiency, crowds out private jobs, delivers bad outcomes, acts in a self-serving fashion, and bankrupts governments.