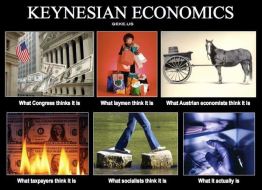

Given the repeated failures of Keynesian economic policy, both in America and around the world,  you would think the theory would be discredited.

you would think the theory would be discredited.

Or at least be treated with considerable skepticism by anyone with rudimentary knowledge of economic affairs.

Apparently financial journalists aren’t very familiar with real-world evidence.

Here are some excerpts from a news report in the Wall Street Journal.

The economy was supposed to get a lift this year from higher government spending enacted in 2018, but so far much of that stimulus hasn’t shown up,

puzzling economists. Federal dollars contributed significantly less to gross domestic product in early 2019 than what economic forecasters had predicted after Congress reached a two-year budget deal to boost government spending. …Spending by consumers and businesses are the most important drivers of economic growth, but in recent years, government outlays have played a bigger role in supporting the economy.

The lack of “stimulus” wasn’t puzzling to all economists, just the ones who still believe in the perpetual motion machine of Keynesian economics.

Maybe the reporter, Kate Davidson,  should have made a few more phone calls.

should have made a few more phone calls.

Especially, for instance, to the people who correctly analyzed the failure of Obama’s so-called stimulus.

With any luck, she would have learned not to put the cart before the horse. Spending by consumers and businesses is a consequence of a strong economy, not a “driver.”

Another problem with the article is that she also falls for the fallacy of GDP statistics.

Economists are now wondering whether government spending will catch up to boost the economy later in the year…

If government spending were to catch up in the second quarter, it would add 1.6 percentage points to GDP growth that quarter. …The 2018 bipartisan budget deal provided nearly $300 billion more for federal spending in fiscal years 2018 and 2019 above spending limits set in 2011.

The government’s numbers for gross domestic product are a measure of how national income is allocated.

If more of our income is diverted to Washington, that doesn’t mean there’s more of it. It simply means that less of our income is available for private uses.

That’s why gross domestic income is a preferable number. It shows the ways – wages and salaries, small business income, corporate profits, etc – that we earn our national income.

Last but not least, I can’t resist commenting on these two additional sentences, both of which cry out for correction.

Most economists expect separate stimulus provided by the 2017 tax cuts to continue fading this year. …And they must raise the federal borrowing limit this fall to avoid defaulting on the government’s debt.

Sigh.

Ms. Davidson applied misguided Keynesian analysis to the 2017 tax cut.

The accurate way to analyze changes in tax policy is to measure changes in marginal tax rates on productive behavior. Using that correct approach, the pro-growth impact grows over time rather than dissipating.

And she also applied misguided analysis to the upcoming vote over the debt limit.

If the limit isn’t increased, the government is forced to immediately operate on a money-in/money-out basis (i.e. a balanced budget requirement). But since revenues are far greater than interest payments on the debt, there would be plenty of revenue available to fulfill obligations to bondholders. A default would only occur if the Treasury Department deliberately made that choice.

Needless to say, that ain’t gonna happen.

Needless to say, that ain’t gonna happen.

The bottom line is that – at best – Keynesian spending can temporarily boost a nation’s level of consumption, but economic policy should instead focus on increasing production and income.

P.S. If you’re a glutton for punishment, you can watch my 11-year old video on Keynesian economics.

P.P.S. Sadly, the article was completely correct about the huge spending increases that Trump and Congress approved when the spending caps were busted (again) in 2018.

———

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery | CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.