I was a big fan of the lower corporate tax rate in last year’s tax bill, largely because I want a better investment climate,  which then will lead to higher productivity and rising wages.

which then will lead to higher productivity and rising wages.

Simply stated, the current tax code (as shown in the chart) has a very harsh bias against income that is saved and invested.

Anything that can be done to reduce the magnitude of this “double taxation” will lead to better economic performance.

Now that the lower corporate tax rate has been implemented, there’s a debate about whether it is having desirable effects.

In this CNBC debate, I explain that stock “buybacks” and employee bonuses are positive short-run results, but that I’m much more interested in the potential long-run benefits.

As with all brief interviews, it’s difficult to share a lot of information. My main goal was to point out that there’s nothing wrong with buybacks for shareholders or bonuses for workers, but that it’s much more important to focus on potential changes in long-run growth.

And we’ll get more long-run growth, I argue, because the lower corporate rate reduces the tax burden on capital (i.e., saving and investment). Jared dismisses this as “trickle-down economics,” but that’s simply his pejorative term for common-sense microeconomics.

But you don’t have to believe me. Many scholars have pointed out that harsh taxes on capital wind up hurting workers. Let’s look at some of the findings from an academic study by Gregory Mankiw, Matthew Weinzierl, and Danny Yagan.

Perhaps the most prominent result from dynamic models of optimal taxation is that the taxation of capital income ought to be avoided. …The intuition for a zero capital tax can be developed in a number of ways. …First, because capital equipment is an intermediate input to the production of future output, the Diamond and Mirrlees (1971) result suggests that it should not be taxed.

Second, because a capital tax is effectively a tax on future consumption but not on current consumption, it violates the Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976) prescription for uniform taxation. In fact, a capital tax imposes an ever-increasing tax on consumption further in the future, so its violation of the principle of uniform commodity taxation is extreme. A third intuition for a zero capital tax comes from elaborations of the tax problem considered by Frank Ramsey (1928). In important papers, Chamley (1986) and Judd (1985) examine optimal capital taxation in this model. They find that…a zero tax on capital is optimal. …any tax on capital income will leave the after-tax return to capital unchanged but raise the pre-tax return to capital, reducing the size of the capital stock and aggregate output in the economy. This distortion is so large as to make any capital income taxation suboptimal compared with labor income taxation, even from the perspective of an individual with no savings.

And here’s some analysis by Garret Jones at George Mason University.

Chamley and Judd separately came to the same discovery: In the long run, capital taxes are far more distorting that most economists had thought, so distorting that the optimal tax rate on capital is zero.

If you’ve got a fixed tax bill it’s better to have the workers pay it. …let me sum up a key implication of Chamley-Judd: Under standard, pretty flexible assumptions, it’s impossible to tax capitalists, give the money to workers, and raise the total long-run income of workers. Not, hard, not inefficient, not socially wasteful, not immoral: Impossible. If you tax capital income and hand all of the tax revenue to workers, then in the long run (or the “steady state”) you’ll wind up with a smaller capital stock. And since workers use the capital stock to earn their wages, the capital tax pushes down their wages.

Even economists on the left agree about the link between productivity and wages. Here’s a recent article from the Wall Street Journal, citing Larry Summers about why wages are still linked to productivity and why growth should still be the goal.

Wages are supposed to track worker productivity… Many on the left argue the link is now broken and redistributing income from the wealthy downward would help workers more than faster economic growth.

But a new study co-authored by Harvard University economist Lawrence Summers says that’s wrong. …The problem, they conclude, is that the positive influence of productivity on pay has been overwhelmed by other forces pushing the other way. …Over one- to five-year periods between 1973 and 2015, they found that a one-percentage-point increase in productivity growth generally led to a 0.5- to one-percentage-point increase in average or median pay growth, depending on the type of workers measured. …In an interview, Mr. Summers says the idea that “policy should shift from growth to inequality is badly misleading.”

Let’s close with some excerpts from an article in the Cayman Financial Review by Orphe Divounguy.

Historically, productivity growth has led to gains in compensation for workers and greater profits for firms. This has big implications for tax policy – especially the degree to which capital is taxed since capital – an essential ingredient to improvements in workers’ living standards –

is highly responsive to changes in the tax climate. …The standard theory of optimal taxation argues that a tax system should maximize social welfare subject to a set of constraints. The goal should be to enact a tax system that maximizes households’ welfare… Pioneering work on optimal taxation is the work of Frank Ramsey (1927), who suggested…only commodities with inelastic demand are taxed. Another important contribution on this topic is the work of James Mirlees (1971), who posits that when a tax system aims to redistribute income from high ability to low ability individuals, the tax system should provide sufficient incentive for high-ability/high-income taxpayers to keep producing… the empirical evidence on the effects of taxation largely supports a move away from capital taxation. …higher taxes on capital income discourage investments in productive capital. This reduction in productive capital causes workers to become less productive, thus causing the real wage to decrease.

Amen. The bottom line is that you can’t punish capital without punishing labor.

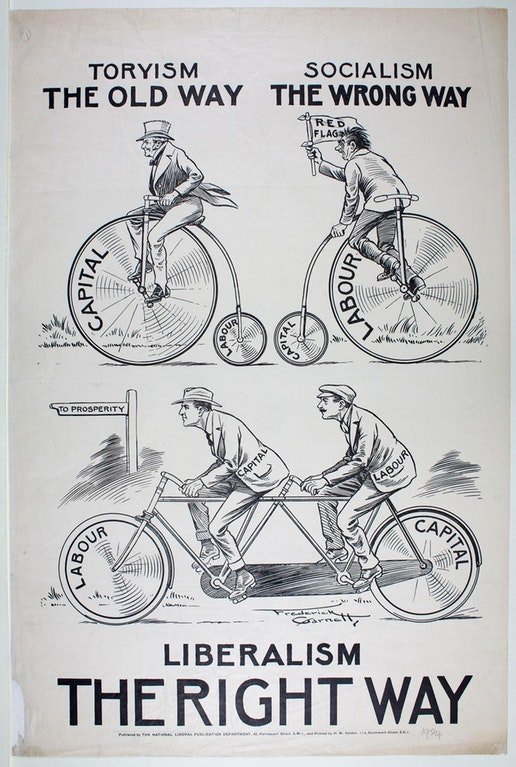

Which is the point of this great cartoon, which I gather was campaign literature at some point for the British Liberal Party (with “liberal” meaning “classical liberal“). It correctly captures the key point about labor and capital being complementary factors of production.

This chart makes the same point.

P.S. I’ve debunked the argument that capital is taxed at a lower rate than labor.