As illustrated by this video tutorial, I’m a big advocate of the Laffer Curve.

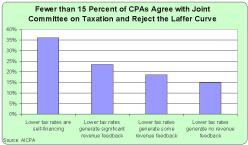

I very much want to help policy makers understand (especially at the Joint Committee on Taxation) that there’s not a linear relationship between tax rates and tax revenue. In other words, you don’t double tax revenue by doubling tax rates.

Having worked on this issue for decades, I can state with great confidence that there are two groups that make my job difficult.

- The folks who don’t like pro-growth tax policy and thus claim that changes in tax policy have no impact on the economy.

- The folks who do like pro-growth tax policy and thus claim that every tax cut will “pay for itself” because of faster growth.

Which was my message in this clip from a recent interview.

For all intents and purposes, I’m Goldilocks in the debate over the Laffer Curve. Except instead of stating that the porridge is too hot or too cold, my message is that it is that changes in tax policy generally lead to more taxable income, but the growth in income is usually not enough to offset the impact of lower tax rates.

In other words, some revenue feedback but not 100 percent revenue feedback.

In other words, some revenue feedback but not 100 percent revenue feedback.

Yes, some tax cuts do pay for themselves. But they tend to be tax cuts on people (such as investors and entrepreneurs) who have a lot of control over the timing, level, and composition of their income.

And, as I said in the interview, I think the lower corporate tax rate will have substantial supply-side effects (see here and here for evidence). This is because a business can make big changes in response to a new tax law, whereas people like you and me don’t have the same flexibility.

But I don’t want this column to be nothing but theory, so here’s a news report from Estonia on the Laffer Curve in action.

After Estonia raised its alcohol excise tax rates considerably in 2017, Estonian daily Postimees has estimated that the target of the

money the alcohol excise tax would bring into state coffers could have been missed by at least EUR 40 million. …Initially, in the state budget of 2017, the ministry had been planned that proceeds from the alcohol excise tax would bring EUR 276.4 million, but last summer, it cut the forecast to EUR 237.5 million.

I guess I’ll make this story Part VII in my collection of examples designed to educate my friends on the left (here’s Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, and Part VI).

But there’s a much more important point I want to make.

The fact that most tax increases produce more revenue is definitely not an argument in favor of higher tax rates.

That argument is wrong in part because government already is far too large. But it’s also wrong because we should consider the health and vitality of the private sector. Here’s some of what I wrote about some academic research in 2012.

…this study implies that the government would reduce private-sector taxable income by about $20 for every $1 of new tax revenue.

Does that seem like good public policy? Ask yourself what sort of politicians are willing to destroy so much private sector output to get their greedy paws on a bit more revenue. What about capital taxation? According to the second chart, the government could increase the tax rate from about 40 percent to 70 percent before getting to the revenue-maximizing point. But that 75 percent increase in the tax rate wouldn’t generate much tax revenue, not even a 10 percent increase. So the question then becomes whether it’s good public policy to destroy a large amount of private output in exchange for a small increase in tax revenue. Once again, the loss of taxable income to the private sector would dwarf the new revenue for the political class.

The bottom line is that I don’t think it’s a good trade to reduce the private sector by any amount simply to generate more money for politicians.

P.S. I’m also Goldilocks when considering the Rahn Curve.

P.P.S. For what it’s worth, Paul Krugman (sort of) agrees with me about the Laffer Curve.

———

Image credit: Gage Skidmore | CC BY-SA 2.0.