At some point in the next 10 years, there will be a huge fight in the United States over fiscal policy. This battle is inevitable because politicians are violating the Golden Rule of fiscal policy by allowing government spending to grow faster than the private sector (exacerbated by the recent budget deal), leading to ever-larger budget deficits.

I’m more sanguine about red ink than most people. After all, deficits and debt are merely symptoms. The real problem is excessive government spending.

But when peacetime, non-recessionary deficits climb above $1 trillion, the political pressure to adopt some sort of “austerity” package will become enormous. What’s critical to understand, however, is that not all forms of austerity are created equal.

The crowd in Washington reflexively will assert that higher taxes are necessary and desirable. People like me will respond by explaining that the real problem is entitlements and that we need structural reform of programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. Moreover, I will point out that higher taxes most likely will simply trigger and enable additional spending. And I will warn that tax increases will undermine economic performance.

The crowd in Washington reflexively will assert that higher taxes are necessary and desirable. People like me will respond by explaining that the real problem is entitlements and that we need structural reform of programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. Moreover, I will point out that higher taxes most likely will simply trigger and enable additional spending. And I will warn that tax increases will undermine economic performance.

Regarding that last point, three professors, led by Alberto Alesina at Harvard, have unveiled some new research looking at the economic impact of expenditure-based austerity compared to tax-based austerity.

…we started from detailed information on the consolidations implemented by 16 OECD countries between 1978 and 2014. …we group measures in just two broad categories: spending, g, and taxes, t. …We distinguish fiscal plans between those that are expenditure based (EB) and those that are tax based (TB)… Measuring the macroeconomic impact of a plan requires modelling the relationship between plans and macroeconomic variables.

Here are their econometric results.

There is a large and statistically significant difference between the effects on output of EB and TB austerity. EB fiscal consolidations have, on average, been associated with a very small downturn in output growth: a spending based plan worth one percent of GDP implies a loss of about half of a percentage point relative to the average GDP growth of the country, which lasts less than two year. Moreover, if an EB austerity plan is launched when the economy is not in a recession, the output costs are zero on average. …On the other hand TB plans are associated with large and long lasting recessions. A TB plan worth one per cent of GDP is followed, on average, by a two percent fall in GDP relative to its pre-austerity path. This large recessionary effect lasts several years.

Here’s a chart from the study showing that economic performance drops farther and farther to the extent taxes are part of an austerity package.

In addition to the core results, the authors explain why tax-based austerity packages are bad for capital…

…investment growth responds very differently following the introduction of the two types of austerity plans. It responds positively to EB plans and negatively to TB plans. …in their sample of OECD countries, business confidence increases immediately at the start of an EB consolidation plan, much more so that at the beginning of a TB plan.

…and why tax-based austerity packages are bad for labor.

…clearly tax hikes and spending cuts – beyond other effects – have different effects on labor supply. …EB plans are the least recessionary the longer lived is the reduction in government spending. Symmetrically, TB plans are more recessionary the longer lasting is the increase in the tax burden and thus in distortions.

Since capital and labor are the two factors of production, the obvious and inevitable conclusion is that the economy does worse when taxes are higher.

The study also makes a critical point about the futility of tax increases when the burden of government spending is rising faster than the private sector. Simply stated, that’s a recipe for ever-increasing taxes, sort of like a dog chasing its tail.

…a TB plan which does not address the automatic growth of entitlements and other spending programs which grow over time if much less like likely to produce a long lasting effect on the budget. If the automatic increase of spending is not addressed, taxes will have to be continually increased to cover the increase in outlays.

That’s why spending restraint is the only way to successfully address red ink.

It doesn’t even require dramatic spending cuts, even though that would be desirable. All that’s needed is some modest fiscal restraint so that spending grows slower than the productive sector of the economy.

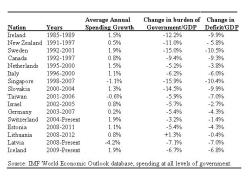

Nations that follow this approach for a multi-year period always get good results. But if you want examples of nations that have achieved good outcomes with tax increases, you’ll have to explore a parallel universe because there aren’t any on this planet.

Nations that follow this approach for a multi-year period always get good results. But if you want examples of nations that have achieved good outcomes with tax increases, you’ll have to explore a parallel universe because there aren’t any on this planet.

P.S. I need to update the table because both the United States (between 2009-2014) and the United Kingdom (between 2010-2016) enjoyed dramatic improvements in fiscal outcomes in recent years because of spending restraint.

P.P.S. Politicians don’t like spending restraint, which is why most periods of good fiscal policy come to an end. To achieve good long-run outcomes, some sort of constitutional spending cap is probably necessary.

P.P.P.S. The study cited above builds upon research I cited in 2016.