Government in America is too big. We are not (yet) at European levels, but unless we turn around the reform trend in the welfare state – which currently points to even bigger government in the near future – we are going to end up with the same macroeconomic problems as the Europeans have.

Our government has sprawled in many directions, first and foremost through the expansion of entitlement programs. This expansion has cemented spending in a way that makes it difficult to reduce the size of government. One reason is the money and other perks that people get from taxpayers, things they will not want to give up without a political fight.

There is another reason why big government has entrenched itself in our economy. The growth in entitlement spending has separated the operational responsibility and the funding of government programs. States and local governments have become the effective producers of much of the American welfare state; at the same time, the federal government is footing an increasing share of the bill – courtesy, of course, of us, the taxpayers.

The growth in the welfare state has not primarily consisted of a growth in the government workforce, at least not relative the private sector. The government employment ratio, which measures the number of federal, state and local government employees per 1,000 private-sector workers, has remained relatively steady over time. Initially, as the welfare state started growing under the War on Poverty, government payrolls swelled:

- In 1957 there were 171 government employees per 1,000 private-sector employees;

- In 1967 the ratio had increased to 212;

- In 1977 it was 227.

More recently, though, the government employment ratio has almost fallen back to its 1950s levels:

- In 1987 it was 202;

- In 1997 it had fallen to 190;

- In 2007 it was at 192.

In 2017 it had declined to 180.

That does not mean the government workforce has stood still. All it means is that its long-term growth has basically stayed on par with the private sector.

The biggest growth of government has come in the form of large entitlement programs and high, distortionary taxes. Many of the programs administered by the government workforce are funded jointly by the federal government and the states, with operational responsibility placed at the state level. Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute has accounted for the growth in these programs, with emphasis on their work-discouraging payouts of benefits.

With the expansion of entitlement spending, the role of government in the U.S. economy has changed fundamentally. This is visible in the composition of federal spending, where national defense has been reduced to a residual, from accounting for half the federal budget when John F Kennedy was president.

It is also visible in the composition of the federal government’s workforce. Even though states and local governments are the primary operators of welfare-state spending, the federal government still spends an inordinate amount of money on Social Security, Medicare and the programs it funds jointly with the states. All these duties demand their workforce.

Predictably, as figure 1 reports, the share of federal employees that work for the constitutionally mandated federal duties, the Department of Defense and the U.S. Postal Service, has gone down over time. The decline has reached a point where these two functions do not even employ half the federal workforce:

Figure 1

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The postal service is not exactly a pinnacle of efficiency and service, and the Department of Defense certainly has its productivity challenges. However, these are the functions that the constitution has given to the federal government, yet despite enumerated powers, more than half of the 2.8 million federal employees have other job descriptions.

While the federal workforce has gradually shifted priorities away from its constitutional duties, states and local governments have grown their employment over time. They have increased their combined share of the total government workforce from 67 percent in 1955 to more than 87 percent today.

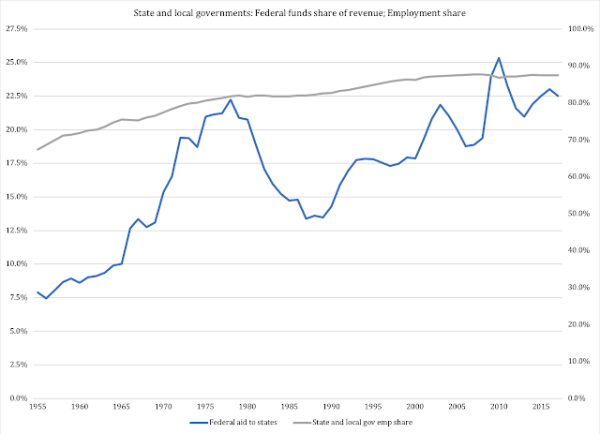

This increase reflects a growth in the responsibility of our states to run programs such as Medicaid, SNAP, WIC, TANF etc.. At the same time, Congress has taken on a growing share of the funding responsibility for these programs. Federal funds as share of state and local government revenue has increased substantially, from eight percent in 1957 to 22.5 percent in 2017. Figure 2 compares these two trends (the employment share is displayed on the right-hand vertical axis):

Figure 2

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (employment), Bureau of Economic Analysis (funding)

There is a big problem hidden under these numbers. As I explained in a paper for the Heritage Foundation in 2008:

These state–federal joint ventures create a number of problems. They make it difficult for voters to hold the President, Senators, Representatives, state legislators, and governors accountable. If New York spends more on Medicaid, is that because New York voters demanded that their state government expand Medicaid or because the voters gave the federal government a mandate to expand the program nationwide? If New York voters want to restrain state spending, should they turn to Albany or Washington? Blurred responsibilities between states and the federal government also make it easier for lawmakers to sneak government-growing bills in under the voters’ radar.

There is a way out of this dilemma: a real block-grant reform that gradually transfers both legislative authority and funding responsibility to the states. That, of course, would require a Congress that is willing to – for once – give up some of its spending and its political power.