We certainly have reasons to celebrate the success of the U.S. economy in 2018. In September, the unemployment rate was at the lowest it has been since 1969, and GDP growth is bound for its highest annual rate in more than ten years.

These are times when government should be running a budget surplus. Yet despite an abundance of tax revenue, Congress is fast-tracking its budget back to trillion-dollar deficits.

Record growth, record employment and record tax revenue, and Congress still cannot pay for its own spending. As the federal budget speeds past $4 trillion, the cause of the deficit problem should be obvious: out-of-control spending.

It is high time for Congress to return to some sort of statutory spending control. The Swiss debt brake comes to mind.

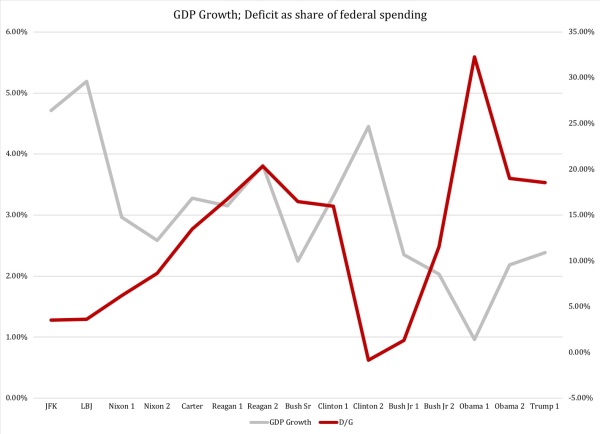

Before we get to that idea, let us take a quick look at some numbers that put the spending problem on painful display. Figure 1 compares average GDP growth per presidential term with the federal budget deficit as percent of total federal spending:

Figure 1

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis (GDP Growth); Office of Management and Budget (Federal budget)

The almost perfect negative correlation between deficits as share of spending, and GDP growth, shows that the deficit is a matter of too much spending. When GDP growth slows down, so does growth in tax revenue. The more closely the deficit varies (inversely) with GDP growth, the more it indicates that spending does not vary with GDP growth.

In other words: when tax revenue slows down, Congress just keeps spending.

As Figure 1 suggests, the Office of Management and Budget predicts that over the next few years the federal government will pay for 17-22 percent of its spending with deficits. This is not fiscally irresponsible. It is fiscally reckless, and it is precisely what hurled countries like Greece, Spain and Portugal into a deep debt crisis during the Great Recession ten years ago. We are heading in the very same direction, and Congress is running out of time to stop it.

I have warned many times about the dangers of spending on credit. I am not alone. Dan Mitchell, for example, has explained eloquently and repeatedly that spending restraint is the key to ending deficits.

To rein in spending, Congress needs to act now. Ideally, that would mean structural reforms to major spending programs. Such reforms would change the very nature of our entitlement programs: spending would no longer increase automatically every year.

In Social Security, for example, this means introducing private accounts that individualize contributions and give people actual control over their own retirement security. In welfare and Medicaid, structural reforms would return the role of government to a last-resort provider of a basic safety net. Today, a relative definition of poverty defines the entire U.S. welfare state as a machine for economic redistribution; an absolute definition of poverty would end the practice of re-engineering economic outcomes. The effect would be a substantial shift in government spending, from steady increases driven by ideological preferences to steady levels that taxpayers can afford, even in hard times.

Unfortunately, structural spending reforms are unrealistic in today’s political climate. A more palatable solution might be the return of some form of statutory spending restraint. However, instead of useless mechanisms (the debt ceiling) and pointless compromises (the sequester) Congress might consider a more intelligent approach: the Swiss debt brake.

Dan Mitchell, a big champion of this mechanism, explained it in a 2012 Forbes Magazine article. In 2016, I analyzed the debt brake in a U.S. context, concluding:

As structural deficits have come to replace cyclical deficits as the dominant kind of fiscal shortfall, credit has de facto become a permanent funding source for government funding. Given that borrowed money is an unsustainable funding source, the question is what measures are needed to end budget deficits. While the European Union has failed in applying a constitutional budget-balancing measure, Switzerland has had some success using a regulatory measure focused on the debt instead of the deficit. While the experience is not unequivocally positive, it is promising enough to be a good example for what type of budget-balancing regulation the United States could have use for.

I also pointed to GDP growth numbers showing that Switzerland had seen a nice bump in economic growth after the debt brake went into effect.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, Swiss debt brake with some moderate modifications is a good idea. It is also a good idea from a legislative viewpoint, as it does not require a constitutional amendment and does not come with the ridiculous political compromises of the sequester.

The road to a fiscal crisis is littered with ignored good ideas. Hopefully, Congress will not ignore this one.