As a general rule, we worry too much about deficits and debt. Yes, red ink matters, but we should pay more attention to variables such as the overall burden of government spending and the structure of the tax system.

That being said, Greece shows that a nation can experience a crisis if investors no longer trust that a government is capable of “servicing” its debt (i.e., paying interest and principal to people and institutions that hold government bonds).

This doesn’t change the fact that Greece’s main fiscal problem is too much spending. It simply shows that it’s also important to recognize the side-effects of too much spending (if you have a brain tumor, that’s your main problem, even if crippling headaches are a side-effect of the tumor).

Anyhow, it’s quite likely that Italy will be the next nation to travel down this path.

This in in part because the Italian economy is moribund, as noted by the Wall Street Journal.

Italy’s national elections…featured populist promises of largess but neglected what economists have long said is the real Italian disease:

The country has forgotten how to grow. …The Italian economy contracted deeply in Europe’s debt crisis earlier this decade. A belated recovery now under way yielded 1.5% growth in 2017—a full percentage point less than the eurozone as a whole and not enough to dispel Italians’ pervasive sense of national decline. Many European policy makers view Italy’s stasis as the likeliest cause of a future eurozone crisis.

Why would Italy be the cause of a future crisis?

For the simple reason that it is only the 4th-largest economy in Europe, but this chart from the Financial Times shows it has the most nominal debt.

So what’s the solution?

The obvious answer is to dramatically reduce the burden of government.

Interestingly, even the International Monetary Fund put forth a half-decent proposal based on revenue-neutral tax reform and modest spending restraint.

The scenario modeled assumes a permanent fiscal consolidation of about 2 percent of GDP (in the structural primary balance) over four years…, supported by a pro-growth mix of revenue and expenditure reforms…

Two types of growth-friendly revenue and spending measures are considered along the envisaged fiscal consolidation path: shifting taxation from direct to indirect taxes, and lowering expenditure and shifting its composition from transfers to investment. On the revenue side, a lower labor tax wedge (1.5 percent of GDP) is offset by higher VAT collections (1 percent of GDP) and introducing a modern property tax (0.5 percent of GDP). On the expenditure side, spending on public consumption is lowered by 1.25 percent of GDP, while productive public investment spending is increased by 0.5 percent of GDP. The remaining portion of the fiscal consolidation, 1.25 percent of GDP, is implemented via reduced social transfers.

Not overly bold, to be sure, but I suppose I should be delighted that the IMF didn’t follow its usual approach and recommend big tax increases.

So are Italians ready to take my good advice or even the so-so advice of the IMF?

Nope. They just had an election and the result is a government that wants more red ink.

The Wall Street Journal‘s editorial page is not impressed by the economic agenda of Italy’s putative new government.

Five-Star wants expansive welfare payments for poor Italians, revenues to pay for it not included. Italy’s public debt to GDP, at 132%, is already second-highest in the eurozone behind Greece.

Poor Italians need more economic growth to generate job opportunities, not public handouts that discourage work. The League’s promise of a pro-growth 15% flat tax is a far better idea, especially in a country where tax avoidance is rife. The two parties would also reverse the 2011 Monti government pension reforms, which raised the retirement age and moved Italy toward a contribution-based benefit system. …Recent labor-market reforms may also be on the block.

Simply stated, Italy elected free-lunch politicians who promised big tax cuts and big spending increases. I like the first part of that lunch, but the overall meal doesn’t add up in a nation that has a very high debt level.

And I don’t think the government has a very sensible plan to make the numbers work.

…problematic for the rest of Europe are the two parties’ demand for an exemption from the European Union’s 3% GDP cap on annual budget deficits. …the two parties want the European Central Bank to cancel some €250 billion in Italian debt.

Demond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute suggests this will lead to a fiscal crisis because of two factors. First, the economy is weak.

Anyone who thought that the Eurozone debt crisis was resolved has not been paying attention to economic and political developments in Italy…the recent Italian parliamentary election…saw a surge in support for populist political parties

not known for their commitment to economic orthodoxy or to real economic reform. …To say that the Italian economy is in a very poor state would be a gross understatement. Over the past decade, Italy has managed to experience a triple-dip economic recession that has left the level of its economy today 5 percent below its pre-2008 peak. Meanwhile, Italy’s current unemployment level is around double that of its northern neighbors, while its youth unemployment continues to exceed 25 percent. …the country’s public debt to GDP ratio continued to rise to 133 percent, making the country the most indebted country in the Eurozone after Greece. …its banking system remains clogged with non-performing loans that still amount to 15 percent of its balance sheet…

Second, existing debt is high.

…having the world’s third-largest government bond market after Japan and the United States, with $2.5 trillion in bonds outstanding, Italy is simply too large a country for even Germany to save. …global policymakers…, it would seem not too early for them to start making contingency plans for a full blown Italian economic crisis.

Since he writes on issues I care about, I always enjoy reading Lachman’s work. Though I don’t always agree with his analysis.

Why, for instance, does he think an Italian fiscal crisis threatens the European currency?

…the Italian economy is far too large an economy to fail if the Euro is to survive in anything like its present form.

Would the dollar be threatened if (when?) Illinois goes bankrupt?

But let’s not get sidetracked.3

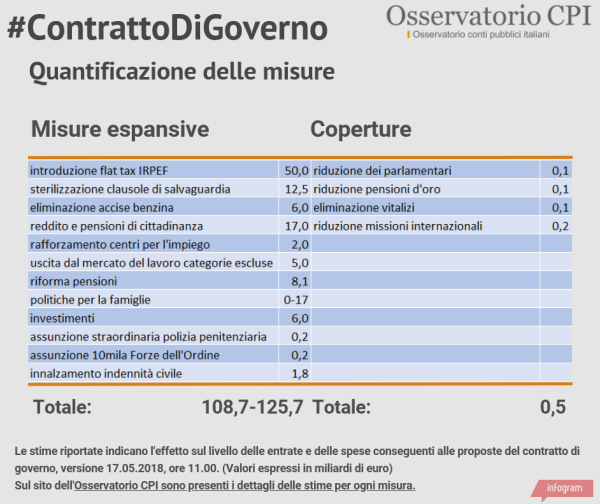

To give you an idea of the fairy-tale thinking of Italian politicians, I’ll close with this chart from L’Osservatorio on the fiscal impact of the government’s agenda. It’s in Italian, but all you need to know is that the promised tax cuts and spending increases are on the left side and the compensating savings (what we would call “pay-fors”) are on the right side.

Wow, makes me wonder if Italy has passed the point of no return.

By the way, Italy may be the next domino, but it’s not the only European nation with fiscal problems.

P.S. No wonder some people want Sardinia to secede from Italy and become part of “sensible” Switzerland.

P.P.S. Some leftists genuinely think the United States should emulate Italy.

P.P.P.S. As a fan of spending caps, I can’t resist pointing out that anti-deficit rules in Europe have not stopped politicians from expanding government.