Political and Economic Risks of a Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax

January 2017

By Brian Garst

Economists widely agree that the corporate tax system in the United States is in need of significant reform. Corporations headquartered in America face the highest statutory and marginal tax rates in the developed world at almost 40 percent (35 percent federal and an average of nearly 5 percent for state governments). The United States also taxes the foreign-source income of U.S.-based multinationals, minus a credit for foreign income taxes paid, once those earnings are repatriated. These policies combine to leave U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage when operating overseas, and discourage them from bringing earnings back to American shores.

The 115th Congress is likely to take up corporate tax reform, either as a stand-alone effort or as part of a broader revision of the overall tax code. At least in the House, the blueprint crafted by Speaker Paul Ryan and House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady titled, “A Better Way: A Pro-Growth Tax Plan for All Americans,” will likely serve as the starting point for any reform package. It contains many pro-growth reforms, including a move toward full expensing for most capital purchases, territoriality, and competitive rate reductions. Unfortunately, these good features are offset by the inclusion of “border adjustability” as part of a destination-based cash flow tax (DBCFT). This provision would undermine the benefits generated by the pro-growth provisions of the plan.

The DBCFT would be a new type of corporate income tax that disallows any deductions for imports while also exempting export-related revenue from taxation. This mercantilist system is based on the same “destination” principle as European value-added taxes, which means that it is explicitly designed to preclude tax competition.

Congressional proponents of the DBCFT mischaracterize its benefits using misguided, protectionist logic. But the main downside of this tax revolves around two broader concerns of political economy. First, the DBCFT is likely to grow government in the long-run due to its weakening of international tax competition and the loss of its disciplinary impact on political behavior. Second, the DBCFT almost certainly violates World Trade Organization commitments. If this simply meant the tax was repealed at some point in the future after being rejected by the WTO, that would be fine. Unfortunately, it is quite possible that lawmakers will try to “fix” the tax by making it into an actual value-added tax rather than something that is merely based on the same anti-tax competition principles as European-style VATs.

Proposed Border-Adjusted Tax

The ostensible selling point of a DBCFT is that it is “border adjustable,” which means that taxes are imposed on what comes into a nation and taxes are removed from what leaves a nation. This mercantilist approach typically is associated with credit-invoice value-added taxes (VATs) that exist in European nations. In the case of the credit-invoice VAT, the tax is supposed to be levied based on where a good is consumed (its destination) rather than where it is produced (its origin). To make the corporate tax destination-based, the Ryan-Brady blueprint exempts from taxation any revenue derived from exports, while not providing for deductions on the cost of imports.

VAT-like Impact on Government Growth

To use the jargon of public finance economists, the DBCFT is a “consumption-base tax” because of policies such as “expensing.” It is conceptually and operationally similar to a subtraction-method VAT in many respects.1 But there’s one key difference between that type of VAT and the DBCFT. Labor compensation (wages, salaries, etc) is deductible under a DBCFT, whereas there is no deduction for those costs with a subtraction-method VAT (which effectively means that a subtraction-method VAT is a hidden withholding tax on labor income in addition to other types of “value added”).

But the close similarity of the VAT and the DBCFT is worrisome for precisely this reason. It would be very simple to turn the latter into the former, and given the fact that the WTO has never allowed a direct tax to be border adjustable, American policymakers might be tempted to respond to an adverse WTO ruling (which would be several years in the future) by simply imposing a VAT. They might even seize the opportunity to increase taxes by keeping the rate at 20 percent and relying on removal of the labor deduction to increase the tax burden.

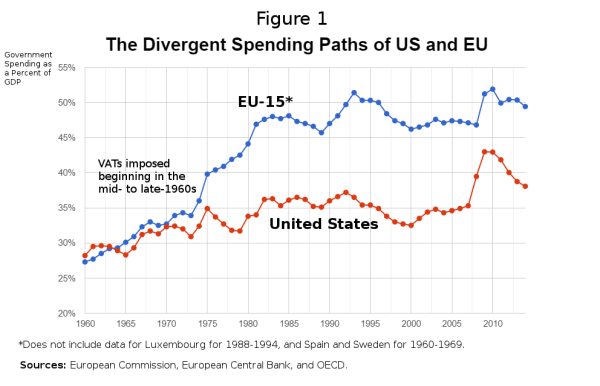

This is a very troubling prospect. Before VATs were widely adopted, European nations featured similar levels of government spending as the United States, as illustrated by Figure 1. Feeding at least in part off the easy revenue generate by their VATs, European nations grew much more drastically over the last half century than the United States and now feature higher burdens of government spending. The lack of a VAT-like revenue engine in the U.S. constrained efforts to put the United States on a similar trajectory as European nations.

If the DBCFT turns into a subtraction-method VAT, its costs would be further hidden from taxpayers. Workers would not easily understand that their employers were paying a big VAT withholding tax (in addition to withholding for income tax). This makes it easier for politicians to raise rates in the future. There also would be the risk that politicians might restore some of the undesirable features of the old corporate income tax, presumably by creating a parallel system that imposed depreciation rather than expensing. Keep in mind that European nations have corporate income tax systems in addition to their onerous VAT regimes.

Uncertain WTO Status

The DBCFT’s VAT-like dangers are compounded by its highly dubious permissibility under WTO rules.2 The question arises in particular with regard to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures.3

For an indirect tax such as the credit-invoice VAT—where the tax is collected by an intermediary instead of the party who bears the economic burden of the tax—the WTO has held that border adjustments are allowed. For direct taxes, however, border adjustments have been considered to be trade distortions. The considerable uncertainty over the DBCFT exists because it happens to be a direct tax on profits, albeit as part of a system that approximates a consumption tax base.4 Where the WTO comes down on the issue is not merely a question of inconvenience. If the DBCFT is ruled as impermissible, then the most politically convenient—and therefore most likely—solution will be to convert it into a standard VAT, government-growing dangers and all.

It’s not even clear if a subtraction-method VAT would get approved by the WTO. After all, such a tax is functionally similar to a regular (i.e., direct) corporate income tax. So the adoption of the DBCFT would represent a risky and untested approach based on a “fingers-crossed” hope that the WTO will bend its rules to favor the United States (notwithstanding the fact that the WTO has not hesitated to rule against America).

Questionable and Uneven Benefits

The Ryan-Brady blueprint claims that the current corporate tax system, whereby some of our trading partners employ border adjustments and the U.S. does not, “amounts to a self-imposed unilateral penalty on U.S. exports and a self-imposed unilateral subsidy for U.S. imports.”5 The mercantilist insistence that border adjustments will benefit exports or provide a competitive trade advantage is commonly cited by politicians, but is not supported by economists.6 You can’t have either imports or exports without the other, thus a tax on one is a tax on both.7 Inclusion of the DBCFT as part of a corporate tax reform package does, however, add unnecessary political obstacles to passage. For instance, it fractures the business community by pitting importers against exporters.8 Businesses would easily unite around the remaining package of reforms if the DBCFT were to be excluded.9

DBCFT supporters insist that the shift to destination-based taxation will increase demand for U.S. goods and strengthen the dollar, and that this will offset the general increase in price levels and ensure no differential impact between high-import and high-export firms.10 There is reason to be skeptical that reality will prove so simple. The efficiency of foreign exchange markets has long been a source of academic debate. According to analysis by Goldman Sachs, “The combination of pegged exchange rates in many trading partners with price stickiness implies that real exchange rates would not adjust as smoothly as implied by current policy proposals.” They conclude that imperfect dollar appreciation will likely lead to higher consumer prices and a threat to the solvency of some net importers.

This is a particular problem for the import-heavy retail industry.11 RBC Capital Markets cautions that “most of our retailers would be forced to raise prices (and revenues) or meaningfully change their import/domestic sourcing mix, or their earnings would be materially reduced.”12 Energy is another sector likely to be heavily impacted. The United States is a net importer of oil and petroleum products. To maintain their current profit margins, refiners of imported crude would need to raise their prices by 25 percent. The price of domestic crude would also rise, varying by the regional reliance on domestic versus imported crude, to reflect what refiners are willing to pay. Ultimately, the higher costs would be reflected at the gas pump, where they would then proliferate throughout the economy. PIRA Energy Group estimates a cost to drivers of 25 cents a gallon.13

If indeed price increases are not offset by currency adjustments, the higher costs on energy and imported consumer goods will lower the standard of living for many Americans. Even if the proponents are right that the dollar will strengthen to some extent, it undermines one of the key parts of the Blueprint—territoriality. Rather than paying U.S. tax, U.S. multinationals will have lower international earnings. The after-tax result is the same.

Undermining Tax Competition

International tax competition is a positive force in the global economy. The 1986 Tax Reform Act, as well as pro-growth reforms in other nations, triggered a a virtuous cycle of rate reductions that saw the average OECD member corporate tax rate cut by almost half—from around 50 percent to under 25 percent today. Many nations subsequently switched to territorial systems, or enacted other pro-growth changes to their tax codes. Reforms occurred despite the oft-stated preference of politicians in these countries to collect more taxes, and to do so in ever more onerous ways. These destructive political impulses were partially restrained by the need to compete for business and investment.

Proponents see the DBCFT as a competitive winner, reasoning that it will pressure companies to move productive assets to the United States. This is a trap. Tax competition works because assets are mobile. This provides pressure on politicians to keep rates from climbing too high. When the tax base shifts heavily toward immobile economic activity, such competition is dramatically weakened. This is cited as a benefit of the tax by those seeking higher and more progressive rates. For instance, one of the top academic proponents of the DBCFT, Michael Devereaux, said at a tax reform conference:

“If other countries have got [the DBCFT], you probably want to have one as well. And then there’s no particular reason to undermine that system by reducing your tax rate. The tax rate is more or less irrelevant within this system. As evidence for that—we don’t observe competition in VAT rates around the world, we do observe competition in corporate tax rates. Why don’t we observe competition in VAT rates? Because it’s on a destination basis. It’s where consumers are and there’s not much they can do about it.”14

Politicians like it when there’s not much taxpayers can do about paying taxes—like changing their behavior in legal ways to lower their tax burdens—because that makes it easier to impose confiscatory tax rates. Another influential proponent of the tax, Alan Auerbach, touts that the DBCFT “alleviates the pressure to reduce the corporate tax rate,” and that it would “alter fundamentally the terms of international tax competition.”15 This raises the obvious question—would those businesses and economists that favor the DBCFT at a 20% rate be so supportive at a higher rate?

The DBCFT’s insulation from tax competition is another reason why it is likely to lead to higher tax burdens in the future. And if other nations were to follow suit and adopt a destination-based system as proponents suggest, it will mean more taxes on U.S. exports. Due to the resulting decline in competitive downward pressure on tax rates, the long-run result would be higher tax burdens across the board and a worse global economic environment. That would be a tragic reverse of what occurred following the 1986 reforms.

Conclusion

Given the overall thrust of their reforms, it is safe to say that Chairman Brady and Speaker Ryan don’t want a more punitive tax system or a heavier fiscal burden. Indeed, it is quite likely that the DBCFT was added to their plan for political reasons (both because it might appeal to protectionist colleagues and because the tax on imports helps to finance other parts of the overall plan). Yet it also brings political risks. If the currency adjustments do not completely offset price increases, any upheaval caused will likely be owned politically by Republicans in the same manner as Obamacare has been by Democrats, especially given the ease with which the latter can sell the idea that Republicans paid for corporate tax cuts on the backs of consumers.

Lawmakers should always consider what is likely to happen once the other side eventually returns to power, especially when they embark upon politically risky endeavors which increase the likelihood of such an outcome. In this case, left-leaning politicians would see the DBCFT not as something to be undone, but as a jumping off point for new and higher taxes. A highly probable outcome is that the United States’ corporate tax environment becomes more like that of Europe, consisting of both consumption and income taxes. The long-run consequences will thus be the opposite of what today’s lawmakers hope to achieve. Instead of a less destructive tax code, the eventual result could be bigger government, higher taxes, and slower economic growth.

To reiterate, it is quite likely that the border-adjusted tax on imports was included to help “pay for” good provisions of the Better Way plan. That is understandable to some degree, but lawmakers should not take such a risky step when the benefits are meager and the dangers are high.

Brian Garst is the Director of Policy and Communications for the Center for Freedom and Prosperity.

Notes

1. For the difference between credit-invoice VAT and subtraction-method VAT, see Curtis S. Dubay, “The Value-Added Tax is Wrong for the United States,” Heritage Foundation, Backgrounder #2503, December 21, 2010. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2010/12/the-value-added-tax-is-wrong-for-the-united-states ↩

2. Greg Ip, “Export-Friendly U.S. Tax Revamp Risks Cool Reception at WTO,” Wall Street Journal, December 21, 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/export-friendly-u-s-tax-revamp-risks-cool-reception-at-wto-1482356641 ↩

3. See Wolfgang Schön, “Destination-Based Income Taxation and WTO Law: A Note,” Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance, Workping Paper 2016-03, January 2016. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=2727628 ↩

4. Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, Kimberly Cluasing, “Problems With Destination-Based Corporate Taxes and the Ryan Blueprint,” University of Michigan Law & Econ Research Paper No. 16-029. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2884903 ↩

5. Paul Ryan, Kevin Brady, A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America, June 24, 2016. pg 28. http://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf ↩

6. See Alan D. Viard, “Border Tax Adjustments Won’t Stimulate Exports,” Tax Notes, American Enterprise Institute, March 2, 2009. https://www.aei.org/publication/border-tax-adjustments-wont-stimulate-exports/ ↩

7. Alan Cole, “When a Tax on Imports is a Tax on Exports,” Tax Foundation, May 21, 2014. http://taxfoundation.org/blog/when-tax-imports-tax-exports ↩

8. Richard Rubin, “House GOP Business-Tax Plan Upends U.S. Policy, Bares Corporate Fault Lines,” Wall Street Journal, November 24, 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/house-gop-business-tax-plan-upends-u-s-policy-bares-corporate-fault-lines-1479996012 ↩

9. Naomi Jagoda, “Biz groups push back on part of GOP tax plan,” The Hill, December 14, 2016. http://www.thehill.com/policy/finance/310375-biz-groups-house-gop-tax-plan-feature-could-cause-huge-business-challenges ↩

10. See Kyle Pomerleau, “Exchange Rates and the Border Adjustment,” Tax Foundation, December 15, 2016. http://taxfoundation.org/blog/exchange-rates-and-border-adjustment ↩

11. Courtney Reagan, “How a controversial GOP plan could boost the taxes on a sweater from $1.75 to $17,” CNBC, December 20, 2016. http://www.cnbc.com/2016/12/20/how-a-controversial-gop-plan-could-boost-the-taxes-on-a-sweater-from-175-to-17.html ↩

12. Brian Faler, “RBC Capital Markets: GOP border-adjustment plan bad for retailers,” Politico Pro, December 2016. ↩

13. Joseph Lawler, “Refiners, drivers could lose under GOP tax plan,” Washington Examiner, December 19, 2016. http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/refiners-drivers-could-lose-under-gop-tax-plan/article/2609897 ↩

14. Michael Devereaux, US corporate tax reform and its implications for the international system: A joint event cosponsored by the International Monetary Fund and AEI, November 14, 2016. http://www.aei.org/events/us-and-international-corporate-tax-reform-a-joint-event-cosponsored-by-the-international-monetary-fund-and-aei/ ↩

15. Alan J. Auerbach, “A Modern Corporate Tax,” Center for American Progress, December 2010. https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2010/12/pdf/auerbachpaper.pdf ↩

———

Image credit: Arealast | CC BY-SA 3.0.