There’s an election next month in the United Kingdom, though there’s not much political suspense.

The Labour Party is led by Jeremy Corbyn, a crazed Bernie Sanders-style leftist, and British voters have no desire to become an Anglo-Saxon version of Venezuela.  Or, since Corbyn’s main economic adviser actually has said all income belongs to the government and Corbyn himself has endorsed a maximum wage, maybe an Anglo-Saxon version of North Korea.

Or, since Corbyn’s main economic adviser actually has said all income belongs to the government and Corbyn himself has endorsed a maximum wage, maybe an Anglo-Saxon version of North Korea.

Given the Labour Party’s self-inflicted suicide, it is widely expected that the Conservative Party, led by Theresa May, will win an overwhelming victory.

But what difference will it make? Will the Tories have a mandate? Do they actually want to change policy?

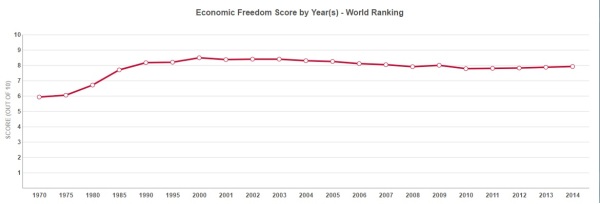

Let’s start by asking whether policy should change. The good news is that the United Kingdom is ranked #10 according to Economic Freedom of the World. That means the U.K. is more market-friendly than the vast majority of nations (including the United States, I’m sad to report).

The bad news is that the U.K.’s score has been slipping throughout the 21st century. Basically, there were a lot of great reforms during the Thatcher era, but policy in recent years has been slowly deteriorating.

More worrisome is that the U.K. – like most developed nations – has a demographic problem.

In the absence of reform, the burden of government automatically will increase.

And that’s a big problem in a nation where a majority of people already are net dependents. In a column for the Telegraph, Daniel Mahoney of the Centre for Policy Studies analyzes this major threat to the U.K.

This week, the Office for National Statistics published figures showing the level of net dependency on the UK state. …The figure now stands at 50.5 per cent. In the 1980s and 1990s, this figure was just over 40 per cent – that is to say that around four in ten households received more in benefits than they paid in taxes. But this dramatically changed in the New Labour era, which left office with well over half of the population being deemed net dependent on the state. …Labour’s enormous increase in spending on public services and welfare was equally responsible for this worrying trend. Public spending grew from just 34.5 per cent of GDP in 2000 to 41% of GDP just before the financial crisis hit the UK… There has been some progress in recent years, …but levels of net dependency remain too high. Over half of households are still net dependent on the state. …It is important for the next Government to reduce dependency further.

But rather than move policy in the right direction, there’s considerable concern that Theresa May is a British version of George W. Bush.

Thatcherites are worried.

Theresa May has been warned not to abandon Margaret Thatcher’s free market economics as she prepares to reveal the most interventionist Tory manifesto for generations. …The Prime Minister has already announced an energy price cap and is expected to clamp down on executive pay and empower workers on boards in her election pitch. …cabinet ministers who served under Mrs Thatcher were scathing of the Prime Minister’s energy price cap when speaking off the record. One said it would create “incredible distortions” in the energy market, while another warned that Government cannot “force water uphill” by trying to stop free-market forces.

If you’re curious about May’s energy policy, Rupert Darwall has a helpful article in The Conservative.

For some time, politicians of all parties have been imposing policies that force up energy costs. Now they want to cut the energy bills that have been driven higher by their own policies. …the Competition and Markets Authority noted the role of decarbonisation policies in pushing up costs. “Pressure on prices is likely to grow in the future, due in part to the increasing costs imposed by climate and energy policies,” the CMA stated. …BEIS ministers have convinced themselves that there is widespread popular support for the aggressive decarbonisation policies that are making energy more expensive. They should have the courage of their convictions and acknowledge that high and rising energy bills are a consequence of the decarbonisation policies they claim are so popular. Once they’ve done that, we can have an honest debate.

Sounds like a classic example of Mitchell’s Law. Politicians pursue a policy (green energy or decarbonisation) that leads to higher prices.  They then respond to the problem created by their intervention with another form of intervention (energy price caps).

They then respond to the problem created by their intervention with another form of intervention (energy price caps).

All of which will cause bigger problems in the future.

But for purposes of today’s column, what matters is that this bad policy is being pushed by the leader of the (supposedly) Conservative Party.

To be sure, it’s possible that this bad policy is just a gimmicky election promise and won’t be implemented. It’s also possible that it will be implemented but will be offset by better policy in other areas.

What matters is whether the overall burden of government is expanding or receding. Maybe May will cap spending (an area where her predecessor did a good job his last few years in office). Maybe she will cut tax rates (the corporate rate already has been slashed and will be reduced to 17 percent over the next few years).

At this stage, there’s no way to predict the direction of policy. But there is reason to worry because there aren’t enough people in the U.K. making the principled case for economic liberty.

Allister Heath explains what is needed to rejuvenate his country.

Britain needs a new movement to sell free-market ideas. It is the only way that this country’s slow drift Left-wards, which began in 1997, will be halted and reversed. It’s the only way that Labour, which has reembraced Marxism under Jeremy Corbyn, and the Tories, which have fallen back in love with old fashioned economic interventionism, will ever see sense again. …Tories gave up fighting for free markets years ago, when David Cameron was elected leader…he decided…to accept all of Labour’s increases in state spending and regulation, including environmental and labour market rules…when the financial crisis struck, the Tories joined in the banker-bashing.

But it’s not just that the Tories did bad things.

They also failed to do good things.

…they didn’t fight from the bully pulpit. They didn’t stand up and explain the merits of low taxes, which boost incentives. They didn’t shout from the rooftops that we need entrepreneurs to create wealth, and that people who make money by selling their wares to the public are performing a public service. They didn’t defend privatisation. They failed to make the case for profits… They conceded too much, including the destructive idea that the private sector is less moral and less law abiding than the state sector. They deferred to egalitarians and class warriors… When the financial crisis came, the Tories didn’t explain that much of it was actually caused by misplaced government intervention, including guarantees extended to financial institutions, pro-sub prime policies in the US, moral hazard and cheap money injected into the system by over-confident central banks. …We now have Mayonomics, a continuation of this trend, and its embrace of Ed Miliband-style energy price caps and yet more interventionism.

So Allister is urging a campaign for economic liberty.

The campaign must explain why private companies that compete against one another always generate better outcomes than public sector monopolies. …All of the lessons that became part of the political conventional wisdom after the 1970s need to be relearnt and retaught, and we need a new generation of pro-free market activists to lead this struggle. It’s time for supporters of capitalism to stand up and be counted.

Sadly, the business community is unwilling to lead.

The big business lobby groups are not up to the task… With a few exceptions, they don’t support real, genuine, free-markets.

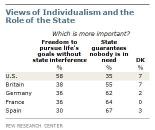

For all intents and purposes, Allister is making the argument that Britain needs to become a more ethical society. In other words, he wants a campaign to inform and educate  about the value of liberty qua liberty. A belief in self-reliance, work, and individual responsibility. Characteristics that could be considered part of social capital or cultural capital.

about the value of liberty qua liberty. A belief in self-reliance, work, and individual responsibility. Characteristics that could be considered part of social capital or cultural capital.

And I think he’s spot on.

I worry a lot about the erosion of social capital in America. But if the polling data is accurate, the problem is much bigger in the United Kingdom.

P.S. Brexit is a wild card in this discussion. I supported the decision to leave the European Union in large part because of my hope U.K. policy makers would feel pressure to shift policy in a more market-oriented direction.