Adopting tax reform (even a watered-down version of tax reform) is not easy.

- Some critics say it will deprive the federal government of too much money (a strange argument since it will be a net tax increase starting in 2027).

- Some critics say it will make it more difficult for state and local governments to raise tax rates (they’re right, but that’s a selling point for reform).

- Some critics say it will make debt less attractive for companies compared to equity (they’re right, though that’s another selling point for reform).

- Some critics say it will cause capital to shift from residential real estate to business investment (they’re right, but that’s a good thing for the economy).

Now there’s a new obstacle to tax reform. Senator Marco Rubio says he wants some additional tax relief for working families. And he’s willing to impose a higher corporate tax rate to make the numbers work.

That proposal was not warmly received by his GOP colleagues since the 20-percent corporate rate was perceived as their biggest achievement.

But now Republicans are contemplating a 21-percent corporate rate so they have wiggle room to lower the top personal tax rate to 37 percent. Which prompted Senator Rubio to issue a sarcastic tweet about the priorities of his colleagues.

20.94% Corp. rate to pay for tax cut for working family making $40k was anti-growth but 21% to cut tax for couples making $1million is fine?

— Marco Rubio (@marcorubio) December 12, 2017

Since tax reform is partly a political exercise, with politicians allocating benefits to various groups of supporters, there’s nothing inherently accurate or inaccurate about Senator Rubio’s observation.

But since I inhabit the wonky world of public finance economics, I want to explain today that there are some adverse consequences to Rubio’s preferred approach.

Simply stated, not all tax cuts are created equal. If the goal is faster economic growth, lawmakers should concentrate on “supply-side” reforms, such as reducing marginal tax rates on work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurship (in which case, it’s a judgment call on whether it’s best to lower the corporate tax rate or the personal tax rate).

By contrast, family-oriented tax relief (a $500 lower burden for each child in a household, for instance) is much less likely to impact incentives to engage in productive behavior.

Most supporters of family tax relief would agree with this economic analysis. But they would say economic growth is not the only goal of tax reform. They would say that it’s also important to make sure various groups get something from the process. So if big businesses are getting a lower corporate rate, small businesses are getting tax relief, and investors are getting less double taxation, isn’t it reasonable to give families a tax cut as well?

As a political matter, the answer is yes.

But here’s my modest contribution to this debate. And I’m going to cite one of my favorite people, myself! Here’s an excerpt from a Wall Street Journal column back in 2014.

The most commonly cited reason for family-based tax relief is to raise take-home pay. That’s a noble goal, but it overlooks the fact that there are two ways to raise after-tax incomes. Child-based tax cuts are an effective way of giving targeted relief to families with children… The more effective policy—at least in the long run—is to boost economic growth so that families have more income in the first place. Even very modest changes in annual growth, if sustained over time, can yield big increases in household income. … long-run growth will average only 2.3% over the next 75 years. If good tax policy simply raised annual growth to 2.5%, it would mean about $4,500 of additional income for the average household within 25 years. This is why the right kind of tax policy is so important.

Now let’s put this in visual form.

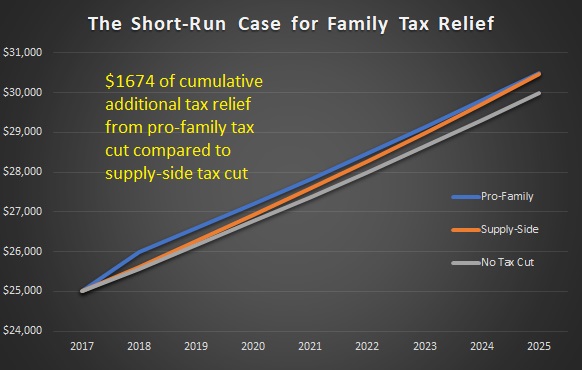

Let’s imagine a working family with a modest income. What’s best for them, a $1,000 tax cut because they have a couple of kids or some supply-side tax policy that produces faster growth?

In the short run, compared to the option of doing nothing (silver line), both types of tax reform benefit this hypothetical family with $25,000 of income in 2017.

But the family tax relief (blue line) is better for their household budget than supply-side tax cuts (orange line).

But what if we look at a longer period of time?

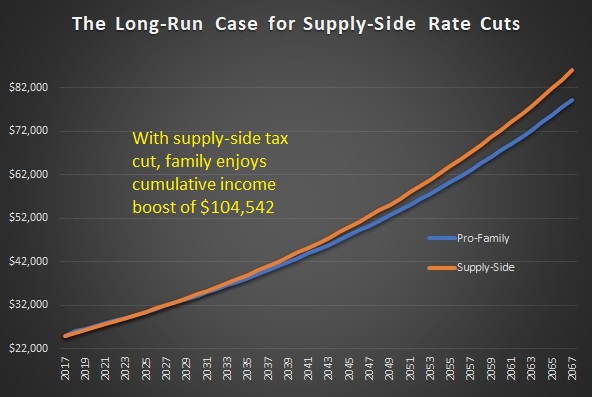

Here’s the same data, but extrapolated for 50 years. And since there’s universal agreement that the status quo is not good for our hypothetical family, let’s simply focus on the difference between family tax relief (again, blue line) and supply-side tax cuts (orange line).

And what we find is that the family actually has more income with supply-side reform starting in 2026 and the gap gets larger with each subsequent year. In the long run, the family is much better off with supply-side tax policies.

To be sure, I’ve provided an artificial example. If you assume growth only increases to 2.4 percent rather than 2.5 percent, the numbers are less impressive. Moreover, what if the additional growth only lasts for a period of time and then reverts back to 2.3 percent?

And keep in mind that money in the future is not as valuable as money today, so the net benefit of picking supply-side tax cuts would not be as large using “present value” calculations.

Last but not least, the biggest caveat is that these two charts are based on the example in my Wall Street Journal column and are not a comparison of the different growth rates that might result from a 20-percent corporate tax rate compared to a 21-percent rate (even a wild-eyed supply-side economist wouldn’t project that much additional growth from a one-percentage-point difference in tax rates).

In other words, I’m not trying to argue that a supply-side tax cut is always the answer. Heck, even supply-side reform plans such as the flat tax include very generous family-based allowances, so there’s a consensus that taxpayers should be able to protect some income from tax and that those protections should be based on family size.

Instead, the point of this column is simply to explain that there’s a tradeoff. When politicians devote more money to family tax relief and less money to supply-side tax cuts, that will reduce the pro-growth impact of a tax plan. And depending on the level of family tax relief and the amount of foregone growth, it’s quite possible that working families will be better off with supply-side reforms.

P.S. A separate problem with Senator Rubio’s approach is that he wants his family tax relief to be “refundable,” which is a technical term for a provision that gives a tax cut to people who don’t pay tax. Needless to say, it’s impossible to give a tax cut to someone who isn’t paying tax. The real story is that “refundable tax cuts” are actually government spending. But instead of having a program where people sign up for government checks, the spending is laundered through the tax code.