You would think the never-ending mess in Afghanistan would have taught us lessons.

Or maybe we might have learned lessons from the never-ending mess in Iraq.

Notwithstanding those unpleasant experiences, President Trump is expanding America’s intervention in Syria with missile strikes.

This rubs me the wrong way, but let’s look at what others are writing on this issue.

One of my colleagues at the Cato Institute, Gene Healy, isn’t impressed by Trump’s intervention.

Thus far, the administration has said nothing about the legal authority for the strikes. There’s not much that can be said: they’re plainly illegal. He had neither statutory nor constitutional authority to order them. …Without statutory cover, all that’s left is an appeal to presidential power under Article II of the Constitution. But that document vests the bulk of the military powers it grants in Congress, with the aim of “clogging, rather than facilitating war,” as George Mason put it. In that framework, the president retains the power to “repel sudden attacks” against the US; but he does not have the power to launch them. …

Kevin Williamson of National Review is equally unhappy with Trump’s unilateral intervention.

As Daniel Pipes and others have persuasively argued, the United States does not have an ally in Syria. The United States does not have any national interest in the success of the ISIS-aligned coalition fighting to depose Assad. The United States does not have any interest in strengthening the position of the Assad regime and the position of his Russian and Iranian patrons. …Of course the Assad regime is murderous. It is murderous in an awfully familiar way: a Baathist despot in cahoots with jihadists using chemical weapons against a civilian population. …The Trump administration has no authorization to engage in war on Syria. Congress has not declared war or authorized the use of military force; there is no emergency to justify the president’s acting unilaterally in his role as commander in chief; there is no imminent threat to American lives or American interests — indeed, there is no real American interest at all. President Donald Trump is acting illegally, and Congress has a positive moral obligation to stop him. …All decent people feel for the Syrians. We also feel for the Ukrainians, the North Koreans, the men and women languishing in Chinese laogai, Russian gulags, and Cuban prisons. We do not go to war for the sake of sentiment. We go to war for the sake of pressing national interests that cannot be otherwise secured. There is no casus belli for knocking over the Assad government, odious as it is.

And Sean Davis of the Federalist asks 14 questions. Here are the ones that caught my attention.

…proponents of military action to depose Assad have not explained is what our clear national security interest is there, what political victory looks like, what our main risks are, and what costs we will be required to pay in order to achieve that victory. …If our nation is going to wage war, and if we are going to pay a price in dollars and in American lives as a result of that decision, we are owed answers to questions that were never adequately answered before we went into Iraq.

1) What national security interest, rather than pure humanitarian interest, is served by the use of American military power to depose Assad’s regime?

2) How will deposing Assad make America safer?

3) What does final political victory in Syria look like (be specific), and how long will it take for that political victory to be achieved? Do you consider victory to be destabilization of Assad, the removal of Assad, the creation of a stable government that can protect itself and its people without additional assistance from the United States, etc.?

6) What costs, in terms of lives (both military and civilian), dollars, and forgone options elsewhere as a result of resource deployment in Syria, will be required to achieve political victory?

8) Should explicit congressional authorization for the use of military force in Syria be required, or should the president take action without congressional approval?

10) If U.S. intervention in Syria does spark a larger war with Russia, what does political victory in that scenario look like, and what costs will it entail?

14) What lessons did you learn from America’s failure to achieve and maintain political victory following the removal of governments in Iraq and Libya, and how will you apply those lessons to a potential war in Syria?

I try to avoid commenting on foreign policy, but all of the excerpts I just shared make total sense. Nobody is claiming that America’s national interests are being threatened. Instead, the case for intervention is that Assad is a bad dictator who is doing bad things.

But if that’s the criteria for intervention, why aren’t we bombing China, Venezuela, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, and the Central African Republic?

Heck, here’s a map from Freedom House. The purple nations are “not free,” which means systematic repression of political rights and civil liberties. Syria is on the list, of course, but if having an oppressive government is what triggers U.S. intervention, there will be perpetual war.

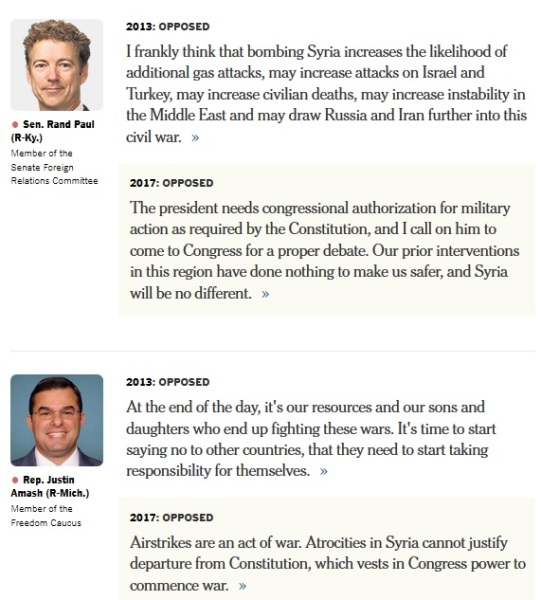

Finally, I can’t help but call attention to a story in the New York Times that looked at many of the Republicans and Democrats who have flipped and flopped when commenting on Obama’s 2013 intervention and Trump’s 2017 intervention.

But there are some notable exceptions, particularly two of the more libertarian-leaning Republicans who actually put principle over partisanship.

And even though I admit I’m not a foreign policy expert, I sometimes play one on TV. And if you look at this interview from 2013, you’ll see that my views also have been consistent.