Now that we have a final bill rather than a mere “agreement in principle,” let’s step back and consider some implications of tax reform.

There are three reasons to be pleased and one reason to worry.

Win: Less-destructive federal tax code

There are several provisions of the tax bill that will boost the economy, most notably dropping the federal corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. Slightly lower individual tax rates will also help growth, as will provisions such as the expanded death tax exemption and the mitigation of the alternative minimum tax.

How much faster will the economy perform? There are several estimates, with microeconomic-based models predicting better outcomes that Keynesian-based models. Here are some findings from two market-based models.

From the Tax Foundation:

…we estimate that the plan would increase long-run GDP by 1.7 percent. The larger economy would translate into 1.5 percent higher wages and result in an additional 339,000 full-time equivalent jobs. Due to the larger economy and the broader tax base, the plan would generate $600 billion in additional permanent revenue over the next decade on a dynamic basis. Overall, the plan would decrease federal revenues by $1.47 trillion on a static basis and by $448 billion on a dynamic basis.

From the Heritage Foundations:

We project that the final bill will increase the level of gross domestic product (GDP) in the long run by 2.2 percent. To put that number in perspective, the increase in GDP translates into an increase of just under $3,000 per household. Though we only estimate the change in GDP over the long run, most of the increase in GDP would likely occur within the 10-year budget window. …the final bill would increase the capital stock related to equipment by 4.5 percent, and the capital stock related to structures by 9.4 percent. We also estimate that the number of hours worked would increase by 0.5 percent.

And here is an estimate from a partially market-based model at the Joint Committee on Taxation:

We estimate that this proposal would increase the level of output (as measured by real Gross Domestic Product (“GDP”) by about 0.7 percent on average over the 10-year budget window. That increase in output would increase revenues, relative to the conventional estimate of a loss of $1,436.8 billion by about $483 billion over that period. This budget effect would be partially offset by an increase in interest payments on the Federal debt of about $55 billion over the budget period. We expect that both an increase in GDP and resulting additional revenues would continue in the second decade after enactment, although at a lower level.*

And here is an estimate from a Keynesian-oriented model at the Tax Policy Center:

We find the legislation would boost US gross domestic product (GDP) 0.8 percent in 2018 and would have little effect on GDP in 2027 or 2037. The resulting increase in taxable incomes would reduce the revenue loss arising from the legislation by $186 billion from 2018 to 2027 (around 13 percent).

For what it’s worth, the market-based (or microeconomic-based) models are more accurate since they are based on the impact of tax-rate changes on incentives to engage in productive behavior.

That being said, proponents of tax reform should not expect Hong Kong-style growth. First, this is only a modest version of tax reform, not a game-changing step such as a simple and fair flat tax. As George Will opined today, “On a scale of importance from one (negligible) to 10 (stupendous), the legislation might be a three.”

Second, keep in mind that fiscal policy only accounts for about 20 percent of a nation’s economic performance. And if taxes and spending each account for half of that grade, policymakers in Washington have positively impacted a variable that determines 10 percent of America’s prosperity.

That may sound discouraging, but even small differences in economic growth make a big difference if sustained over time. As I noted in 2014:

…very modest changes in annual growth, if sustained over time, can yield big increases in household income. … long-run growth will average only 2.3% over the next 75 years. If good tax policy simply raised annual growth to 2.5%, it would mean about $4,500 of additional income for the average household within 25 years.

Win: Pressure for better tax policy in other nations

I consider myself to be the world’s bigger cheerleader and advocate of tax competition. I’ve even risked getting thrown in jail to promote fiscal rivalry between nations. And I’ve written several times about how this tax reform package is good because it will encourage better tax policy abroad (see here, here, and here).

I’ll bolster my argument today by sharing some excerpts from a Wall Street Journal editorial.

German economists at the Center for European Economic Research (ZEW) released a study last week finding that U.S. corporate tax reform will sharply improve incentives for foreigners to invest in America—at the expense of high-tax countries such as Germany.

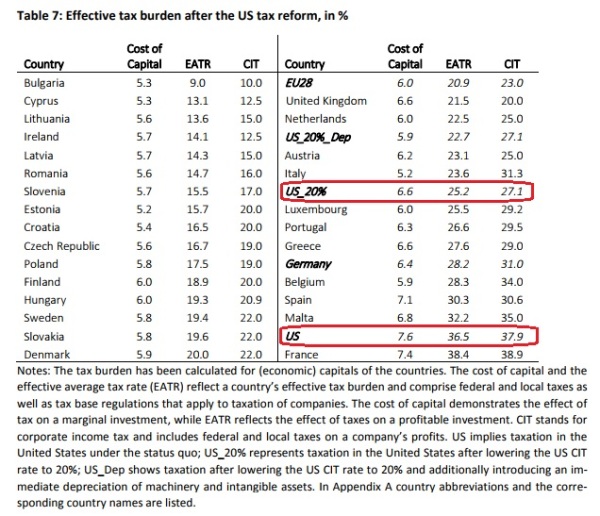

…In the ZEW model, U.S. firms needed a return of around 7.6% for an investment to be profitable under pre-reform tax law, compared to an EU average of 6%, and 5.7% in low-tax Ireland. The U.S. reform changes all this. America’s statutory and effective corporate rates will both be near the EU average, essentially even with Britain and the Netherlands and well below France (a 39% headline rate) and Germany (31%). …Companies from low-tax Ireland, high-tax Germany and the EU as a whole would all see their effective tax rates and their cost of capital for U.S. investment plummet under the reform.

Another German think tank reached a similar conclusion.

US administrations have refrained from any major corporate tax reform since that implemented by Reagan in 1986. This passivity has been remarkable in the sense that most industrial countries have put forward considerable corporate tax cuts in the last decades. This long period of inaction has now come to an end. …Without doubt, this far reaching corporate tax reform of the largest economy will change the setting of international tax competition.

And how will it change the setting?

First, a caveat. The German study looked at the likely impact of a 20-percent corporate rate, so keep in mind that updated numbers to reflect the 21-percent rate in the final deal would look slightly different.

Second, the corporate tax burden in the United States is still going to higher than the European average, even after the 21-percent rate is implemented. Here’s a chart from the German study and I’ve highlighted the current U.S. position and the post-tax reform position (“US_20%_Dep” is where we would be if “expensing” had been included).

Third, even though the reduction in the corporate rate is just a modest step in the right direction, it’s going to yield major benefits.

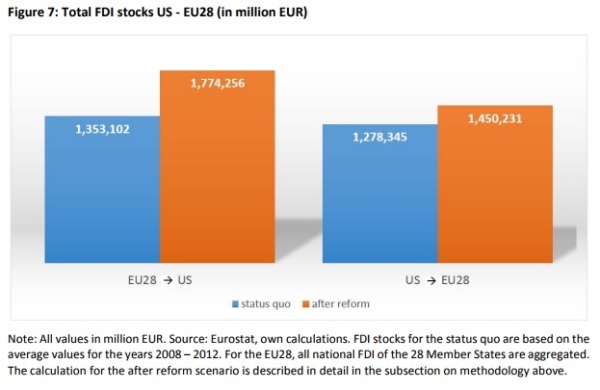

The US tax reform will affect the net-of-tax profitability of both inbound and outbound FDI as well as domestic investments. …in the case of Germany the reduction in the tax burden for German FDI in the US outweighs the reduction of the tax burden for US outbound FDI in Germany by almost factor 3. …FDI stocks in a country increases by 2.49% if the tax rate is reduced by one percentage point. … despite the overall expansion after the US tax reform which is expected to foster FDI in all countries, the US will benefit disproportionally by additional inward FDI. This comes at the cost of European countries which will face increasing outbound FDI flows to the US which are not accompanied with inbound FDI flows from the US in the same amount. …After the implementation of the US corporate tax reform, manufacturing FDI be particularly expanded. The US will attract additional inbound FDI of 113.5 billion EUR from investors located in the EU28. … European high-tax jurisdictions such as Germany will most likely be confronted with a higher net outflow of investments than European low-tax jurisdictions such as Ireland. Ultimately, the European high-tax jurisdictions will lose ground in the competition for FDI.

And here’s another chart from the study. It shows that it will be somewhat more profitable for U.S. companies to compete abroad, and a lot more profitable for foreign investors to put money in America.

Win: Pressure for better state tax policy

As I’ve repeatedly argued, getting rid of the deduction for state and local taxes is a very desirable policy. On the federal level, it’s good because that reform frees up some revenue that can be used to offset lower tax rates. On the state level, it’s good because politicians in high-tax areas will now feel a lot of pressure to lower tax rates.

Or, if you look at the glass being half empty, they’ll feel pressure not to further increase tax rates.

The Wall Street Journal has a new editorial on this topic, asking “how much will they have to cut income-tax rates to retain and attract the high-income earners who finance so much of their state budgets?”

The mere possibility is caused great angst in some circles.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo last weekend declared that the GOP bill’s limit on the state-and-local tax deduction will trigger “an economic civil war” between high- and low-tax states. California Governor Jerry Brown has likened Republicans to “mafia thugs” while Mr. Cuomo calls the bill a “dagger at the economic heart of New York.”

Though only a select slice of taxpayers will be impacted, and some of them are in red states.

…the tax math will be tricky for many high-earners in states with the highest tax rates. …high earners in states with top rates exceeding 6.56% could see their tax bills increase.

The nearby table shows the 17 states with top income-tax rates exceeding 6.56%. The four with the highest income tax rates have Democratic Governors—California, New York, Oregon and Minnesota—and liberal political cultures heavily influenced by public unions. …Iowa ranks fifth with a top rate of 8.98% that hits at a mere $70,785 for married couples, which is more punitive than even New Jersey’s 8.87% that hits households making more than $500,000. Wisconsin (7.65%), Idaho (7.4%), South Carolina (7%), Arkansas (6.9%) and Nebraska (6.84%) are among Donald Trump -voting states that also make the high-tax list. …This ought to put pressure on high-tax Midwestern states such as Wisconsin, Iowa and Minnesota to reduce their rates.

But the ultra-high-tax blue states are the ones that will really feel the squeeze to lower tax rates.

…limiting the deduction will increase the existing rate divide between high- and low-tax states. New York, New Jersey and Connecticut have been losing billions of dollars each year in adjusted gross income from high earners fleeing to lower tax climes like Florida. Nevada will become an even more attractive tax haven for wealthy Californians. The problem is more acute when you consider that the top 1% of earners pay nearly 50% of state income taxes in California and New York, and 37% in New Jersey. States may experience significant budget carnage if more high earners defect. To head off a high-earner revolt, Mr. Cuomo could seek to eliminate the millionaire’s tax he campaigned against in 2010 but has repeatedly extended. Mr. Brown could campaign to repeal the 3% surcharge on millionaires he championed in 2012.

Loss: Failure to restrain federal spending puts tax reform at risk

Now that we’ve looked at three reasons to be optimistic about tax reform, let’s close with some grim news.

Republicans could have produced a far bolder tax reform plan had they been willing to restrain spending. That didn’t happen.

Instead, they only were able to produce a tax bill that featured a very modest – and temporary – amount of tax relief.

Instead, they only were able to produce a tax bill that featured a very modest – and temporary – amount of tax relief.

And because they were constrained by the budget numbers, many of the provisions impacting individuals are sunset at the end of 2025.

It’s not just a question of not doing the right thing. Republicans are actually making matters worse on the spending side of the budget. They are busting the budget caps and doing a lot of so-called emergency spending.

All this will come back to bite them when it’s time extend (or, better yet, make permanent) the provisions that are scheduled to expire. The bottom line if that it’s impossible to have a good tax code with an ever-growing burden of government spending.

* The Joint Committee on Taxation estimate is for the House-passed version of tax reform. An estimate of the final bill hasn’t been released, though it presumably will be similar.