The great thing about the Economic Freedom of the World is that it’s like the Swiss Army Knife of global policy. No matter where you are or what issue you’re dealing with, EFW will offer insight about how to generate more prosperity.

Since today’s focus is Central America, let’s look at the EFW data.

As you can see, it’s a mixed bag. Some nations are in the top quartile, such as Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Panama, though none of them get high absolute scores. Mexico, by contrast, has a lot of statism and is ranked only #88, which means it is in the third quartile. And Belize is a miserable #122 and stuck in the bottom quartile (where Cuba also would be if that backwards country would be ranked if it produced adequate statistics).

One of the great challenges for development in Central America (as well as other parts of the developing world) is figuring out how to get poor and middle-income nations to make the jump to the next level.

Mary Anastasia O’Grady of the Wall Street Journal has a column on how to get more growth in Central America. She focuses on Guatemala, but what she writes is applicable for all neighboring countries.

…faster economic growth is part of what’s needed for the region… To succeed, it will have to break with the State Department’s conventional wisdom that underdevelopment is caused by a paucity of taxes and regulation. It will also have to climb down from its view that trade is a zero-sum game. Policy makers might start by reading a new report on micro, small and medium-sized businesses in Guatemala by the Kirzner Center for Entrepreneurship at Francisco Marroquin University in Guatemala City. It measures—by way of household surveys in 179 municipalities and interviews with industry experts—“attitudes, activities and aspirations of the entrepreneur.” …the GEM study ranks Guatemala No. 1 for its positive view of entrepreneurship as a career choice. Guatemala also ranks high (No. 9) for the percentage of the population engaged in new businesses, defined as less than 3½ years old. And it ranks 12th in terms of the percentage of the population who “are latent entrepreneurs and who intend to start a business within three years.”

She explains that Guatemalan entrepreneurship is hampered by excessive taxation and regulation.

Yet Guatemalan eagerness to run a business has not translated into prosperity for the nation… The country ranks a lowly 59th in entrepreneurs’ expectations that they will create six or more jobs in five years. It also sinks to near the bottom of the pack (62nd) in creating business-service companies. …The World Bank’s 2017 “Doing Business” survey provides many clues about why the informal economy is so large. Guatemala ranks 88th out of 190 countries world-wide for ease of running an enterprise, but in key categories that make up the index it performs much worse. The survey finds that it takes 256 hours to comply with the tax code. The total tax take is 35.2% of profits. It takes almost 20 days to start a legal enterprise and costs 24% of per capita income. To enforce a contract it takes more than 1,400 days and costs more than 26% of the claim.

The good news is that we know the answers that will generate prosperity. The bad news is that Guatemala gets a lot of bad advice.

The obvious solution is an overhaul of the tax, regulatory and legal systems in order to increase economic freedom. A lower tax rate and a simpler code would give companies an incentive to operate legally, thereby broadening the base and improving access to credit. Instead the Guatemalan authorities—encouraged by the State Department and the International Monetary Fund—spend their resources trying to impose a complex, costly system in an economy of mostly informal businesses with a much-smaller number of legal, productive entrepreneurs. Recently the United Nations International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala recommended a new tax to fight “impunity.” This is no way to attract capital or raise revenue.

Speaking of bad advice, let’s now contrast the sensible recommendations of Ms. O’Grady to the knee-jerk statism of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. In a new report on Costa Rica’s tax system, the OECD urged ever-higher fiscal burdens for the country. Including destructive class warfare.

Costa Rica’s tax revenues are…insufficient to finance the country’s current spending needs. …In addition to raising more tax revenue…, Costa Rica needs to…enhance the redistributive role of its tax system. …the role of the personal income tax (PIT) should be strengthened as it currently raises little revenue and does not contribute to reducing inequality. …Collecting greater revenues from the PIT, by lowering the income threshold above which PIT has to be paid as well as by introducing additional PIT brackets and gradually raising the top PIT rate, could contribute to reducing income inequality.

But the OECD doesn’t merely want to hurt successful taxpayers.

The bureaucracy is proposing other taxes that target everyone in the country. Including a pernicious value-added tax.

Costa Rica does not have a modern VAT system in place. …Costa Rica’s priority should be to introduce a well-designed and broad-based VAT system…to be able to generate additional revenues… There is scope to improve the environmental effectiveness of tax policy while also increasing revenue.

So why is the OECD so dogmatically in favor of higher taxes in Costa Rica?

Are revenues less than 5 percent of GDP, indicating that the country is unable to finance genuine public goods such as rule of law?

Is the government so starved of revenue that Costa Rico can’t replicate the formula – a public sector consuming about 10 percent of economic output – that enabled the western world to become rich?

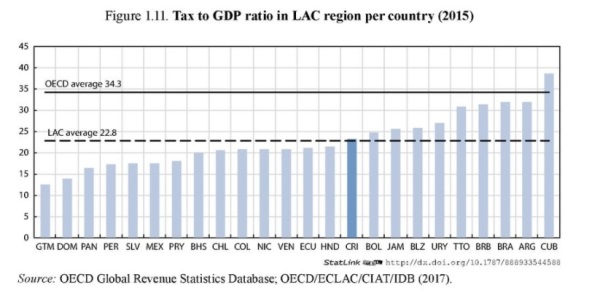

Of course not. The report openly acknowledges that the Costa Rican tax system already consumes more than 23 percent of GDP.

The obvious conclusion if that the burden of government in Costa Rica should be downsized. And that’s true whether you think that the growth-maximizing size of government, based on the experience of the western world, is 5 percent-10 percent of GDP. Or whether you limit yourself to modern data and think the growth-maximizing size of government, based on Hong Kong and Singapore, is 15 percent-20 percent of economic output.

Here’s another amazing part of the report, as in amazingly bad and clueless.

The OECD actually admits that rising levels of government debt are the result of spending increases.

…significant increases in expenditures have not been matched by increases in tax revenues. …Between 2008 and 2013, overall government spending increased as a result of higher public sector remuneration as well as higher government transfers to finance public sector social programmes.

What’s particularly discouraging, as you just read, is that the higher spending wasn’t even in areas, such as infrastructure, where there might arguably be a potential for some long-run economic benefit.

Instead, the government has been squandering money on bureaucrat compensation and the welfare state.

Here’s another remarkable admission in the OECD report.

The high tax burden is a key driver of the informal economy in Costa Rica. The IMF estimated the size of the informal economy in Costa Rica at approximately 42% of GDP in the early 2000s… Past work from the IMF showed that rigidities in the labor market and the high tax burden were the most important drivers of informality.

Yet does the OECD reach the logical conclusion that Costa Rica needs deregulation and lower tax rates? Of course not.

The Paris-based bureaucrats instead want measures to somehow force workers into the tax net.

Bringing more taxpayers within the formal economy should be a key priority. …the tax burden in Costa Rica is borne by a small number of taxpayers. This puts a limit on the amount of tax revenue that can be raised…and puts a limit to the impact of the tax system in reducing inequality.

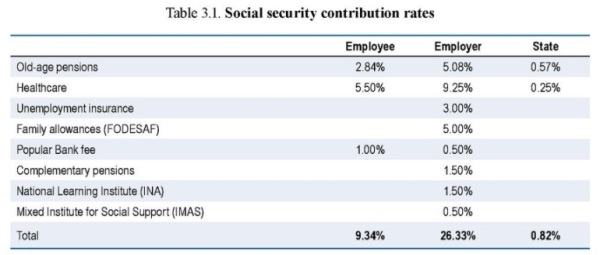

Ironically, the OECD report actually includes a table showing why the IMF is right in this instance. As you can see, social insurance taxes create an enormous wedge between what it costs to employ a worker and how much after-tax income a worker receives.

In other words, the large size of the underground economy is a predictable consequence of high tax rates.

Let’s conclude with the sad observation that the OECD’s bad advice for Costa Rica is not an anomaly. International bureaucracies are routinely urging higher tax burdens.

Indeed, I joked a few years ago in El Salvador that the nation’s air force should shoot down any planes with IMF bureaucrats in order to protect the country from bad economic advice.