When I debate my leftist friends on the minimum wage, it’s often a strange experience. When other people are listening or watching, they’ll adopt a very extreme position and basically claim that politicians have the power to dramatically boost take-home pay by simply mandating higher levels of pay. And somehow there won’t be any noticeable negative impact on employment and labor markets, even though businesses only create jobs if they expect some net profit.

But when we talk privately, they have a more nuanced argument. They’ll confess that higher minimum wages will cause some low-skilled workers to become unemployed, but then justify that outcome using either or both of these arguments.

- Amoral utilitarianism – A large number of people will get pay raises and only a small handful will lose their jobs,

and this is okay if policy is based on some notion of greatest good for the greatest number. In other words, you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.

and this is okay if policy is based on some notion of greatest good for the greatest number. In other words, you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs. - Keynesian stimulus – Some people will lose their jobs, but the income gains for those who keep their jobs will boost “aggregate demand” and thus provide a boost for the economy. Sort of like they also claim giving people unemployment benefits will somehow generate more economic activity.

I’ve always rejected the first argument because I believe in the individual right of contract. The government should not prevent an employer and employee from engaging in voluntary exchange.

And I’ve always rejected the second argument because there can’t be any net “stimulus” since any additional income for workers is automatically offset by less income for employers.

So who is right?

Well, the real world just kicked advocates of higher minimum wages in the teeth. Or maybe even someplace even more painful. A new study from the National Bureau of Economic Research looks at the impact of the $11 and $13 minimum wages in the city of Seattle and finds very bad results.

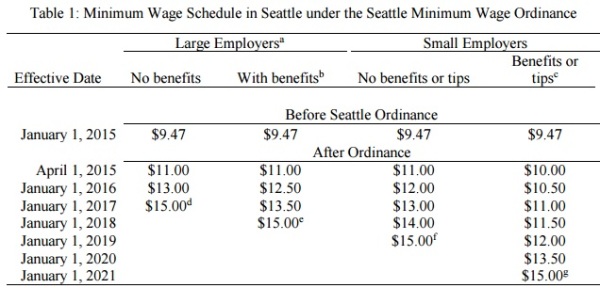

Let’s start by simply citing what the local government did.

This paper, using rich administrative data on employment, earnings and hours in Washington State, re-examines this prediction in the context of Seattle’s minimum wage increases from $9.47 to $11/hour in April 2015 and to $13/hour in January 2016.

And here’s a table from the study, showing details on the minimum-wage mandate.

And what’s been happening as a result of this intervention in the labor market?

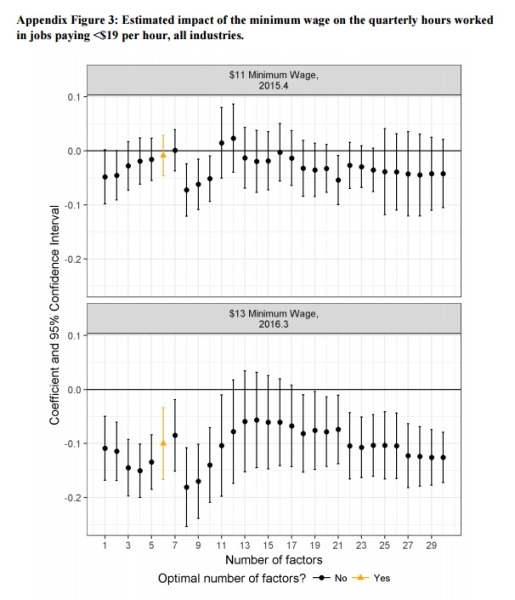

Unsurprisingly, the jump to $13 has been much more damaging that the jump to $11.

…conclusion: employment losses associated with Seattle’s mandated wage increases are in fact large enough to have resulted in net reductions in payroll expenses – and total employee earnings – in the low-wage job market. …We show that the impact of Seattle’s minimum wage increase on wage levels is much smaller than the statutory increase, reflecting the fact that most affected low-wage workers were already earning more than the statutory minimum at baseline. Our estimates imply, then, that conventionally calculated elasticities are substantially underestimated. Our preferred estimates suggest that the rise from $9.47 to $11 produced disemployment effects that approximately offset wage effects, with elasticity estimates around -1. The subsequent increase to as much as $13 yielded more substantial disemployment effects, with net elasticity estimates closer to -3.

Here’s a chart from the study looking at the impact on hours worked.

If you want a healthy labor market, it’s not good to be below the line.

And here’s some of the explanatory text.

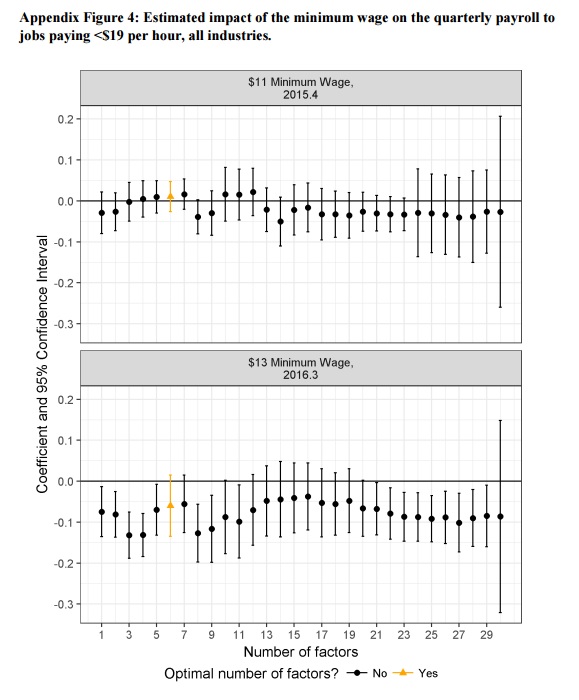

…Because the estimated magnitude of employment losses exceeds the magnitude of wage gains in the second phase-in period, we would expect a decline in total payroll for jobs paying under $13 per hour relative to baseline. Indeed, we observe this decline in first-differences when comparing “peak” calendar quarters, as shown in Table 3 above. …point estimates suggest payroll declines of 4.0% to 7.6% (averaging 5.8%) during the second phase-in period. This implies that the minimum wage increase to $13 from the baseline level of $9.47 reduced income paid to low-wage employees of single-location Seattle businesses by roughly $120 million on an annual basis. …Our preferred estimates suggest that the Seattle Minimum Wage Ordinance caused hours worked by low-skilled workers (i.e., those earning under $19 per hour) to fall by 9.4% during the three quarters when the minimum wage was $13 per hour, resulting in a loss of 3.5 million hours worked per calendar quarter. Alternative estimates show the number of low-wage jobs declined by 6.8%, which represents a loss of more than 5,000 jobs.

But the biggest takeaway from the report is that hours dropped so much that the average low-wage worker wound up with less income

The reduction in hours would cost the average employee $179 per month, while the wage increase would recoup only $54 of this loss, leaving a net loss of $125 per month (6.6%), which is sizable for a low-wage worker.

Here’s the relevant chart.

Once again, it’s not good to be below the line.

This data is remarkable because it shows that higher minimum wages are a bad idea, even according to the metrics of our friends on the left.

- The amoral utlitarianism argument doesn’t apply because it’s no longer possible to claim that income gains for those keeping jobs will more than offset income losses for those who become unemployed.

- The Keynesian aggregate-demand argument doesn’t apply because it’s no longer possible to assert macroeconomic benefits based on the assumption of a net increase in “spending power” in the economy.

Let’s close with a couple of observations from others who have looked at the new study.

Diana Furchtgott-Roth of the Manhattan Institute (and formerly Chief Economist at the Department of Labor) highlights the most relevant findings.

Raising the pay floor has led to net losses in payroll expenses and worker incomes for low-wage workers. …When hourly wages rose from $11 to $13 in 2016, hours of work and earnings for low-wage workers were reduced by 9 percent for the first three calendar quarters, resulting in 3.5 million fewer hours worked for each calendar quarter. The number of jobs declined by 7 percent, with the result that 5,000 jobs were lost. …The evidence shows that in Seattle, low-wage workers got less money in their pockets, rather than more.

Some proponents of intervention and mandates may want to dismiss Diana’s analysis since of her reputation as a market-friendly scholar.

But even Ben Casselman and Kathryn Casteel of FiveThirtyEight basically reach the same conclusion.

As cities across the country pushed their minimum wages to untested heights in recent years, some economists began to ask: How high is too high? Seattle, with its highest-in-the-country minimum wage, may have hit that limit. …New research released Monday by a team of economists at the University of Washington suggests the wage hike may have come at a significant cost: The increase led to steep declines in employment for low-wage workers, and a drop in hours for those who kept their jobs. Crucially, the negative impact of lost jobs and hours more than offset the benefits of higher wages — on average, low-wage workers earned $125 per month less because of the higher wage.

I’m amused to find more evidence that left-leaning economists admit that higher minimum wages cause damage, albeit never on the record.

Even some liberal economists have expressed concern, often privately, that employers might respond differently to a minimum wage of $12 or $15, which would affect a far broader swath of workers.

I’m wondering how they can look at themselves in the mirror. It seems very immoral (in other words, beyond amoral) to publicly defend a policy that you privately admit is bad.

I understand that this type of dishonesty happens all the time in the political world (for example, some Republicans are now supporting Trump’s plans for infrastructure boondoggles and parental leave when they would have been strongly opposed if the same policies had been proposed by Obama).

But what’s the point of being a tenured academic if you can’t at least be honest?

Though maybe there’s some sort of cognitive dissonance at play, where they feel the rules of honesty don’t apply in the political world. For instance, both Paul Krugman and Larry Summers have acknowledged in their academic work that unemployment benefits lead to more unemployment. But they pretend that’s not the case when commenting on the policy debate.

But I’m digressing. Let’s close by recycling this CF&P video on minimum wages.