Since Republicans screwed up Obamacare repeal and haven’t even tried to impose spending restraint, I was rather pessimistic about tax reform earlier this year.

Given my dour attitude, I thought the best-possible outcome was nothing more than a reduction in the corporate tax rate.

But now I’m actually somewhat hopeful that we’ll get a lower corporate rate and repeal of the pernicious deduction for state and local income taxes.

And I’m even wondering whether I should allow myself to hope that the death tax can be repealed. The final outcome will depend on negotiations on Capitol Hill. The House bill gets rid of the tax (albeit only for people who can stay alive a few more years). The Senate bill isn’t as good since it only increases the exemption.

Is it possible the final deal will kill this destructive form of double taxation?

Folks on the left are afraid it may happen. The New York Times is predictably editorializing in favor of keeping the tax.

“Only morons pay the estate tax,” Gary Cohn, Mr. Trump’s chief economic adviser, told Senate Democrats, meaning, it was later explained, “rich people with really bad tax planning.”

Many of the very wealthy use loopholes, like trusts, to avoid paying inheritance tax. …An estate tax repeal would provide a tax windfall of more than $3 million apiece for the top 0.2 percent of earners, and more than $20 million for the wealthiest Americans. It would cost $239 billion in revenue over a decade. It offers nothing for middle-class people, except more evidence of Mr. Trump’s and Republicans’ bad faith.

Frankly, I don’t care whether rich people benefit. I want the tax repealed because it penalizes saving and investment.

The actual victims of the tax (the “morons” who failed to hire clever lawyers and accountants) are forced to liquidate assets and turn the money over to government.

And potential victims of the tax engage in inefficient forms of tax planning to protect assets from the government.

Call me crazy, but I want capital to be allocated efficiently since that’s one of the keys for economic growth and rising wages.

The U.K.-based Economist has just published a defense of the death tax that begins by acknowledging that it’s not a popular levy.

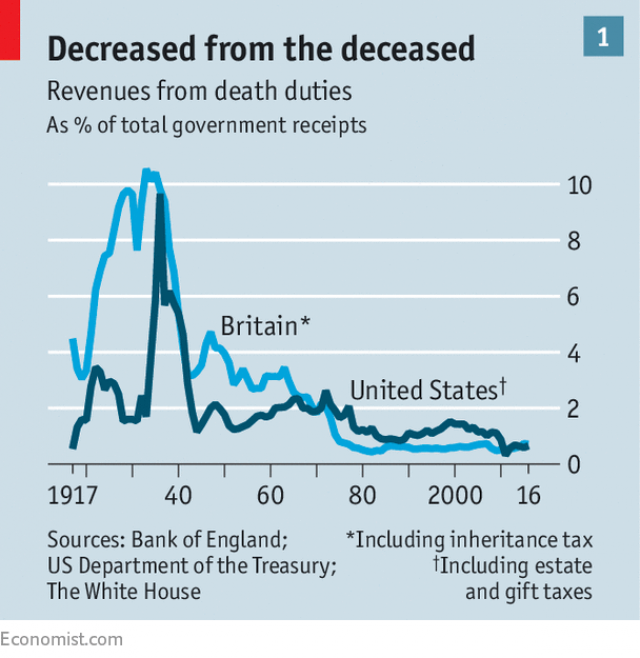

Inheritance tax is routinely seen as the least fair by Britons and Americans. This hostility spans income brackets. …The estate of a dead adult American is 95% less likely to face tax now than in the 1960s.

…For a time before the second world war, Britons were more likely to pay death duties than income tax; today less than 5% of estates catch the taxman’s eye. It is not just Anglo-Saxons. Revenue from these taxes in OECD countries, as a share of total government revenue, has fallen sharply since the 1960s. Many other countries have gone down the same path. In 2004 even the egalitarian Swedes decided that their inheritance tax should be abolished.

Notwithstanding the magazine’s name, the article shows very little understanding of economics.

…this trend towards trifling or zero estate taxes ought to give pause. Such levies pit two vital…principles against each other. One is that governments should leave people to dispose of their wealth as they see fit. The other is that a permanent, hereditary elite makes a society unhealthy and unfair. How to choose between them? …The positive argument for steep inheritance taxes is that they promote fairness and equality. …Unlike capital-gains taxes, heavier estate taxes do not seem to dissuade saving or investment.

I’m glad that the article pays lip service to the notion that people should be able to decide how to spend their own money, but then the article veers into pure class warfare.

What’s really remarkable, though, is that we’re supposed to believe that death taxes don’t have a negative impact on capital formation (i.e., saving and investment). Utter nonsense.  Let’s think this through. Imagine a successful entrepreneur who earns income and gets hit with, say, a 40 percent personal income tax. That entrepreneur than invests some of the after-tax income, which then presumably triggers additional layers of tax (business taxes, capital gains taxes, dividend taxes), which easily can confiscate 30 percent of affected funds. And then there can be a death tax that may grab another 40 percent.

Let’s think this through. Imagine a successful entrepreneur who earns income and gets hit with, say, a 40 percent personal income tax. That entrepreneur than invests some of the after-tax income, which then presumably triggers additional layers of tax (business taxes, capital gains taxes, dividend taxes), which easily can confiscate 30 percent of affected funds. And then there can be a death tax that may grab another 40 percent.

At the risk of plagiarizing the New York Times, only a “moron” is going to ignore the cumulative impact of all those taxes. There’s either going to be less quantity of saving and investment or less quality of saving and investment (because of inefficient tax planning).

Fortunately, governments in the real world increasingly understand that death taxes are very damaging. In another article, the Economist shares some specific details on how death taxes have become less popular around the world.

In OECD countries the proportion of total government revenues raised by such taxes has fallen by three-fifths since the 1960s, from over 1% to less than 0.5%. Over the same period Australia, Canada, Russia, India and Norway are among countries that have abolished death duties. More than 20 American states binned wealth-transfer taxes between 1976 and 2000… In 1976 roughly 8% of American estates filed a taxable return; that has since fallen to around 0.2%.

I actually think tax competition deserves a lot of the credit for the good reforms that have happened, but that’s an issue for another day.

Here’s a chart from the article, which is supposed to show how death taxes have become a smaller and smaller share of tax revenue. This seems like good news, but keep in mind that what it really shows is that personal income taxes, payroll taxes, and (in the U.K.) the value-added tax have grown enormously since the pre-World War II era. If the Economist wanted to be honest, it would have shown inflation-adjusted death tax revenue.

I can’t resist commenting on one other thing. The Economist wants people to think that the death tax is okay because compliance costs supposedly are modest.

A study published in 1999 suggests that the overall cost of estate-tax compliance is 7% of estate-tax revenues. Yet a chunk of those costs, such as selecting executors and drafting documents, would still be paid even in the absence of the tax. So it is hardly clear that the rich would be left with much extra time for more productive undertakings.

I’m skeptical of their compliance calculations, but let’s set that aside.

What the article overlooks (and what is far more important from an economic perspective) is that the death tax causes capital to be misallocated. Successful families make decisions about saving and investment based on potential tax implications rather than what is most productive. And really successful families create trusts and foundation to protect their wealth. Good for them (and good for their financial advisers), but not so good for everyone else since money won’t be used as efficiently.

And if you don’t think the death tax distorts incentives, consider that evidence from Australia indicates it even impacts when people die.

I’m not going to hold my breath, but it would be great news if congressional Republicans can kill the death tax.