If tax policy was a religion, the Holy Trinity of reform would be very straightforward.

- Lower tax rates in order to encourage more productive behavior.

- Get rid of double taxation in order to enable saving and investment.

- End distorting preferences in order to reduce economically irrational decisions.

But if tax policy was a meal, the first two items would be the dessert and the last item would be the vegetable. Simply stated, politicians like lowering tax rates and reducing double taxation because that makes most people happy (at least the ones who actually pay tax).

But when you take away loopholes, the people who benefit from those preferences are unhappy. And they get very noisy. Interest groups hire lobbyists. Trade associations spring into action. Campaign contribution get dispensed.

If tax policy was a movie, it would be Revenge of the Swamp Creatures.

In this clip from a recent interview, I talk about some of the dessert, specifically a much-needed reduction in the corporate tax rate.

But today I want to focus more on the vegetables of itemized deductions.

Here’s some of what Reuters reported last month about the swamp gearing up to protect its privileges.

…industry groups and other sectors of society are gearing up to fight proposed changes to the personal income tax. …proposed changes to the personal tax code have already stirred opposition from realtors, home builders, mortgage lenders and charities.

And here’s a description of what might happen and the impact.

To simplify the tax code, Republicans have proposed eliminating nearly all tax write-offs including those for state and local taxes, then doubling the standard deduction. This would eliminate the incentive to itemize and should drastically reduce the number of taxpayers who do so. Currently, many taxpayers use itemized deductions, claiming write-offs for things like charitable contributions, interest paid on a mortgage and state and local taxes. If the standard deduction becomes larger, fewer taxpayers will need to itemize, reducing the incentive to hold a mortgage or contribute to charity. …Estimates suggest more than half of taxpayers would stop itemizing under the proposed plan.

Should we hope that these reforms occur? If people lose or forego itemized deductions, would that be a good outcome?

As a long-time fan of the flat tax, I’m obviously not a fan of these preferences. Though I always stress that I only want to get rid of loopholes if the money is used to finance lower tax rates. At the risk of stating the obvious, I don’t want the money being used to finance bigger government.

Let’s see what others have said, starting with Justin Fox’s column for Bloomberg. He’s not happy that loopholes disproportionately benefits taxpayers with above-average incomes.

Let’s talk about upper-middle-class entitlements, the subsidies that flow almost entirely to those in the upper fifth or even tenth of the income distribution. …Why do these subsidies continue…? Mainly, it seems, because they’ve been granted to a sizable, influential population who, it is feared, will fight any effort to take them away. There are other interested parties, too — the real estate industry and mortgage lenders in the case of the mortgage interest deduction… But mainly it’s the millions of upper-middle-class Americans who, like me and my family, are beneficiaries of tax subsidies.

He’s right. I’m more upset about the economic distortions these preference create, but there’s no doubt that upper-income taxpayers reap most of the benefits.

Here’s his conclusion, which I think is spot on.

…if these tax breaks had never become law, no one would really miss them. Houses might cost a bit less. College might be slightly cheaper. Income tax rates might be a little lower. The economy might run a little bit more smoothly. So … how do we get to that place from here?

By the way, Fox includes a chart showing how richer taxpayers get more benefit from the mortgage interest deduction.

That’s certainly true, and I’ve previously shared data showing how the middle class gets almost nothing from itemized deductions compared to high-income taxpayers.

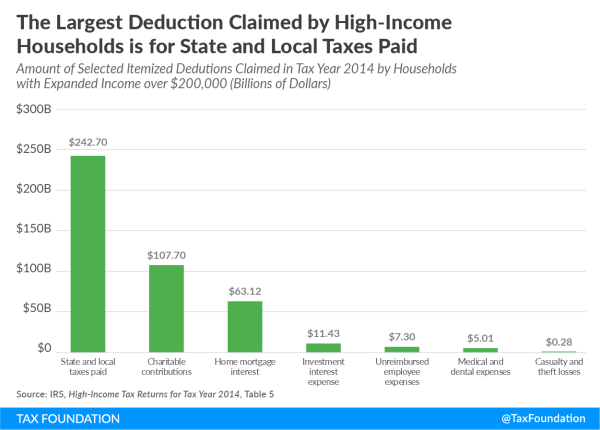

Let’s focus specifically on those goodies for the rich. This chart from the Tax Foundation reveals that the state and local tax break is especially lucrative.

For what it’s worth, the state and local deduction is my least favorite, so I’d like to see this chart change.

Though the healthcare exclusion may do even more economic damage (I assume it’s not included in the above chart since it’s an exclusion rather than a deduction).

But the bottom line of today’s column is that we’re not going to get the dessert of lower tax rates unless policy makers are willing to eat some vegetables – i.e., get rid of some tax preferences. Or, to be more exact, it will be impossible, given congressional budget rules, to have any sort of meaningful permanent reforms of the tax system unless there are revenue raisers to offset the tax cuts.

P.S. In any discussion of tax preferences, it’s important to properly define a loophole. Folks on the right generally think income should be taxed only one time (technically, they favor “consumption-base” taxation). So a loophole is a provision that results in zero tax on a particular activity.

Folks on the left generally think the tax code should impose double taxation (technically, they favor “Haig-Simons” taxation). So they have a much bigger list of loopholes, mostly focused on provisions that limit the extra layers of tax imposed on income that is saved and invested. You see this approach from the Joint Committee on Taxation. You see it from the Government Accountability Office. You see it from the Congressional Budget Office. Heck, you even see Republicans mistakenly use this benchmark.

By the way, Justin Fox presumably is in the Haig-Simons camp since his column treats the capital gains tax and 401(k)s as loopholes. But he cited one of my columns, so I can’t bring myself to criticize him.

P.P.S. It (almost) goes without saying that many folks on the left want to curtail tax breaks. They openly argue that it is good to divert a larger share of income into the hands of politicians and in order to facilitate bigger government. Some of them are even honest enough (crazy enough?) to openly assert that all income belongs to the government.