A new annual edition of Economic Freedom of the World has been released.

The first thing that everyone wants to know is how various nations are ranked.

Let’s start at the bottom. I can’t imagine that anybody will be surprised to learn that Venezuela is in last place, though we don’t know for sure the worse place in the world since the socialist hellholes of Cuba and North Korea weren’t included because of a lack of acceptable data.

the worse place in the world since the socialist hellholes of Cuba and North Korea weren’t included because of a lack of acceptable data.

At the other end, Hong Kong is in first place, where it’s been ranked for decades, followed by Singapore, which also has been highly ranked for a long time. Interestingly, the gap between those two jurisdictions is shrinking, so it will be interesting to see if Singapore grabs the top spot next year.

New Zealand and Switzerland are #3 and #4, respectively, retaining their lofty rankings from last year.

The biggest news is that Canada plunged. It was #5 last year but now is tied for #11. And I can’t help but worry what will happen in the future given the leftist orientation of the nation’s current Prime Minister.

Another notable development is that the United Kingdom jumped four spots, from #10 to #6. If that type of movement continues, the U.K. definitely will prosper in a post-Brexit world.

And if we venture outside the top 10, I can’t help but feel happy that the United States rose from #16 to #11. And America’s ranking didn’t jump merely because other nations adopted bad policy. The U.S. score increased from 7.75 in last year’s report to 7.94 in this year’s release.

A few other things that grabbed my attention are the relatively high scores for all the Baltic nations, the top-20 rankings for Denmark and Finland, and Chile‘s good (but declining) score.

Let’s take a look at four fascinating charts from the report.

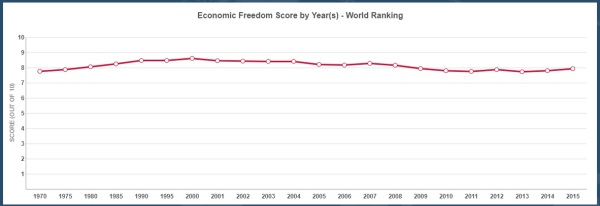

We’ll start with a closer look at the United States. As you can see from this chart, the United States enjoyed a gradual increase in economic freedom during the 1980s and 1990s, followed by a gradual decline during most of the Bush-Obama years. But in the past couple of years (hopefully the beginning of a trend), the U.S. score has improved.

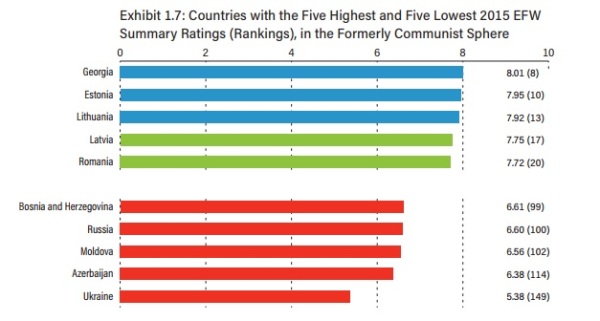

Now let’s shift to the post-communist world.

What’s remarkable about nations from the post-Soviet Bloc is that you have some big success stories and some big failures.

I already mentioned that the Baltic nations get good scores, but Georgia and Romania deserve attention as well.

But other nations – most notably Ukraine and Russia – remain economically oppressed.

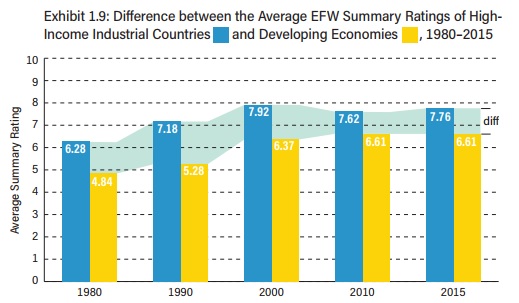

Our next chart shows long-run developments in the scores of developed and developing nations.

Both sets of countries benefited from economic liberalization in the 19890s and 1990s. But the 21st century has – on average – been a period of policy stagnation.

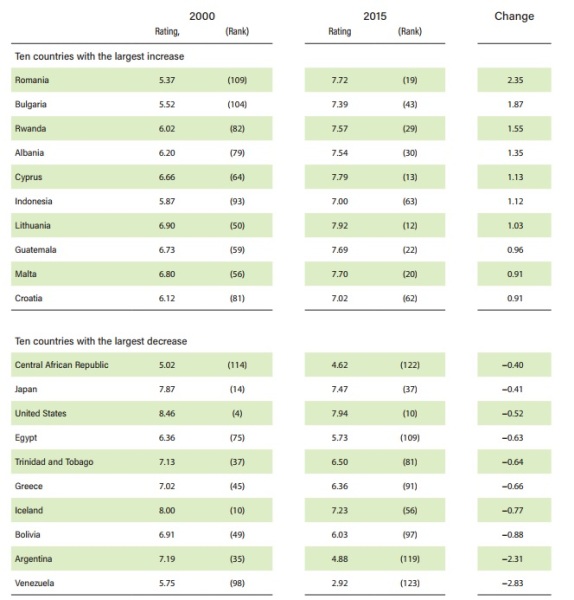

Last but not least, let’s look at the nations that have enjoyed the biggest increases and suffered the biggest drops since 2000.

A bunch of post-communist nations are in the group that enjoyed the biggest increases in economic liberty. It’s also good to see that Rwanda’s score has jumped so much.

I’m unhappy, by contrast, so see the United States on the list of nations that experienced the largest reductions in economic liberty since the turn of the century.

Greece’s big fall, however, is not surprising. And neither are the astounding declines for Argentina and Venezuela (Argentina improved quite a bit in this year’s edition, so hopefully that’s a sign that the country is beginning to recover from the horrid statism of the Kirchner era).

Let’s close with a reminder that Economic Freedom of the World uses dozens of variables to create scores in five major categories (fiscal, regulatory, trade, monetary, and rule of law). These five scores are then combined to produce a score for each country, just as grades in five classes might get combined to produce a student’s grade point average.

This has important implications because getting a really good score in one category won’t produce strong economic results if there are bad scores in the other four categories. Likewise, a bad score in one category isn’t a death knell if a nation does really well in the other four categories.

As a fiscal policy wonk, I always try to remind myself not to have tunnel vision. There are nations that may get good scores on fiscal policy, but get a bad overall score because of poor performance in non-fiscal variables (Lebanon, for instance). Similarly, there are nations that get rotten scores on fiscal policy, yet are ranked highly because they are very market-oriented in the other four variables (Denmark and Finland, for example).