Singapore is one of my favorite nations for the simple reason that it consistently gets very high scores from Economic Freedom of the World and the Index of Economic Freedom (as well as from Doing Business, Global Competitiveness Report, and World Competitiveness Yearbook).

I also greatly admire Singapore’s strict adherence to my Golden Rule for a 10-year period beginning in the late 1990s. Government spending actually shrank by a bit more than 1 percent per year, on average, over that decade.

I also greatly admire Singapore’s strict adherence to my Golden Rule for a 10-year period beginning in the late 1990s. Government spending actually shrank by a bit more than 1 percent per year, on average, over that decade.

This reduced the burden of government spending to just 12 percent of economic output, almost as low as it was in North America and Western Europe in the 1800s.

Unfortunately, the public sector has since crept back up to 20 percent of GDP, but that’s still very low compared to the rest of the developed world.

What’s especially attractive is that the welfare state is very small in Singapore. According to the IMF (see page 44), expenditures on “social development” are only about 8 percent of GDP, and that category includes education and health care. If you peruse Singapore budget documents, spending on “transfers” is well under 5 percent of economic output.

Either figure is far below levels of redistribution in other developed nations.

One of the reasons the welfare state is so small is that individuals are required to set aside their own money for health and retirement.

And since the burden of spending is modest, that enables Singapore to have a non-oppressive tax regime.

- A top personal income tax rate of 22 percent (about half the U.S. level)

- A corporate tax rate of 17 percent (less than half the U.S. level).

- No death tax (unlike most other developed nations).

- No capital gains tax (unlike most other developed nations).

- Very little double-taxation of interest and dividends (unlike most other developed nations).

That’s the good news. The bad news is that a value-added tax was imposed back in the 1990s. Though the rate has stayed low (so far) and hasn’t (yet) become a money machine for big government.

Singapore is also very good in areas other than fiscal policy. It is a shining example of the benefits of open trade. It ranks very highly for rule of law. And there’s very little regulation.

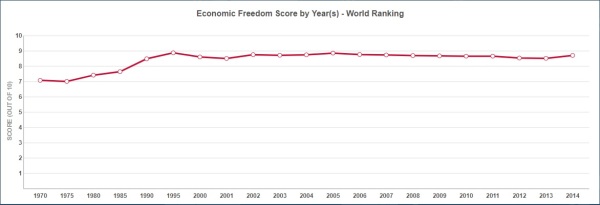

Indeed, Singapore has consistently ranked #2 for economic freedom in recent decades, trailing only Hong Kong (the U.S. briefly edged out Singapore for second place after all the market-friendly reforms of the Reagan and Clinton years, but now we trail by a wide margin thanks to the statism of the Bush-Obama years).

Here’s a graph from Economic Freedom of the World showing how Singapore started at a decent point in 1970 and then had a 20-year period of improvement (most because of deregulation and better monetary policy).

As I repeatedly argue, if you want good economic results, you need good policy.

And that’s exactly the story of Singapore.

I’m currently in the country because I spoke earlier today at a conference on global investment (the audience got quite excited when I explained the effort to defund the OECD).

Walking the streets, it’s hard not to be impressed by the widespread prosperity of the jurisdiction. Sleek buildings. Fancy shops. Lots of professionals.

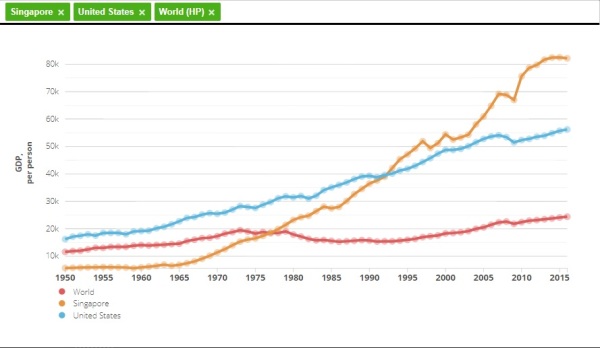

And ordinary people are the biggest winners. Here’s a remarkable chart from Human Progress showing per capita GDP (in $2015 inflation-adjusted dollars) in Singapore and the United States, along with the world average.

As you can see, Singapore used to be far below the United States and somewhat below the world average. Now it is one of the wealthiest places on the planet.

Singapore’s jump from poverty to prosperity is astounding.

What’s really remarkable is that the country was as poor as Jamaica back in the 1960s. But thanks to rapid economic growth, the people of Singapore enjoy very high living standards today.

The moral of the story is that ordinary people in Singapore enjoy prosperity because the government was smart enough to focus on growth and didn’t worry about inequality.

Here’s what Marian Tupy, one of my colleagues at the Cato Institute, wrote about the country’s incredible growth.

The incredible transformation of Singapore from a sleepy outpost of the British Empire to a global commercial and technological hub was partly facilitated by a very high degree of economic freedom. …As late as 1970, per person income in Singapore was 54 percent of the global average. Today it is 321 percent of the global average.

Now for the bad news.

Singapore is very pro-market, but it’s not very pro-liberty. In an article for the Foundation for Economic Education, Donovan Choy highlights some of the nation’s shortcomings.

Within libertarian circles, Singapore generally enjoys a good reputation for its economic freedom.

But it’s not Nirvana.

The Housing Development Board (HDB), the public housing arm of the state, houses more than 80% of the population in high-rise apartment homes. …Education is largely monopolized by the state from the primary school level up until the university level… Singapore suffers from a severe lack of press freedom, ranking at an alarming 151 in the World Press Freedom Index… The state also controls public broadcasting from television to radio. …Singapore is perhaps most well-known for its non-tolerance of drugs. Drug users can be jailed or housed in rehabilitation centers for up to three years and drug traffickers face the death penalty. …Singaporean males are also subject to mandatory conscription of up to two years by the age of 18, a law that has been in effect since 1967. Civil ownership of guns are outlawed in Singapore.

These are reasons why Singapore does not earn a high score in the Human Freedom Index.

But I’m an economist, so I’m still as positively impressed as I was back in 2009.

P.S. The bureaucrats at the OECD produced a report on Asian economies and argued that taxes should consume at least 25 percent of GDP to achieve prosperity, which was a remarkable assertion since the report showed that Singapore was the richest nation in the region and has a tax burden barely half that level. That’s an example of what soccer fans call an “own goal.” The OECD wasn’t just being statist, it was being incompetently statist.

———

Image credit: Merlion444 | CC0 1.0.