Remember John Kerry, the former Secretary of State and Massachusetts Senator, the guy who routinely advocated higher taxes but then made sure to protect his own wealth? Not only did he protect much of his fortune in so-called tax havens, he even went through the trouble of domiciling his yacht outside of his home state to minimize his tax burden.

I didn’t object to Kerry’s tax avoidance, but I was irked by his hypocrisy. If taxes are supposed to be so wonderful, shouldn’t he have led by example?

At the risk of understatement, folks on the left are not very good about practicing what they preach.

But let’s not dwell on John Kerry. Instead, let’s focus on other yacht owners so we can learn an important lesson about tax policy.

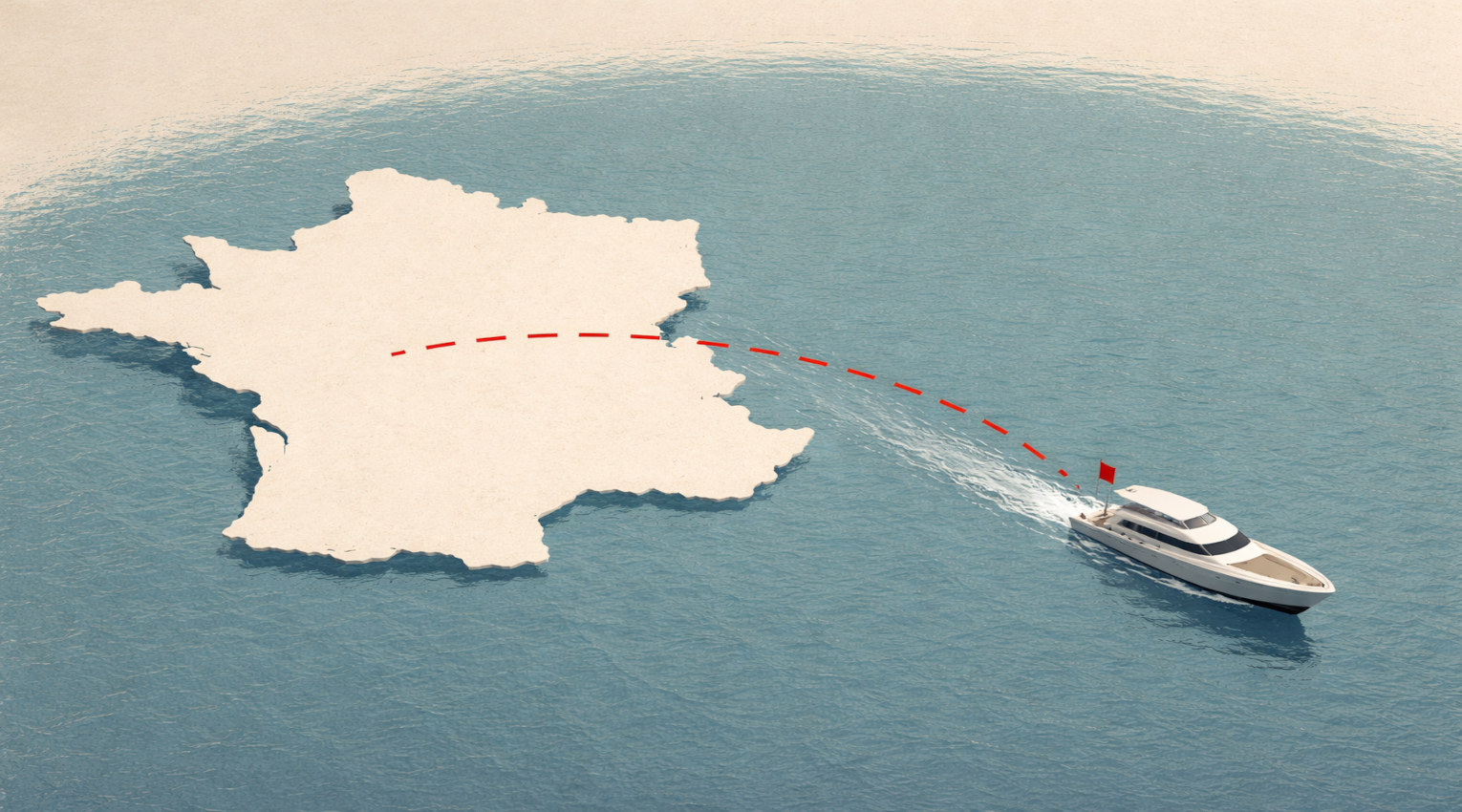

And, as is so often the case, France is an example of the policies to avoid.

Where have all the superyachts gone? That is the question that locals and business owners in the south of France are asking this summer. And the answer appears to be: Italy, Greece, Turkey, and Spain. …While the ongoing presence of €10 cups of coffee and €1000 bottles of Champagne might serve to reassure the casual observer that the region is still as attractive to the sun-loving super-rich as it ever was, appearances can be deceptive. Talk to locals involved in the multibillion-euro yachting sector—and in the south of France that’s nearly everyone, in some trickle-down shape or form, as yachting is by some measures the biggest earner in the region after hotels and wine—and you detect a sinking feeling. …More and more yachting money is draining away…washing up in other European countries such as Spain, Italy, Greece, and Turkey.

Having once paid the equivalent of $11 for a diet coke in Monaco, I can confirm that it is a painfully expensive region.

But let’s focus on the more important issue: Why are the big yachts staying away from the French Riviera?

Apparently, they’re avoiding France for the same reason that entrepreneurs are avoiding France. The tax burden is excessive.

The core reason for the superyacht exodus is financial; France has tightened…tax regulations for the captains and crew members of yachts who officially reside in France, and often have families on the mainland, but traditionally have evaded all tax by claiming they were earning their salary offshore. The country has also taken a hard line on imposing 20 percent VAT on yacht fuel sales, which often used to be dodged. Given that a typical fill can be around €100,000, it is understandable that many captains are simply sailing around the corner.

I don’t share this story because I feel sorry for wealthy people.

Instead, the real lesson to be learned is that when politicians aim at the rich, it’s the rest of us that get victimized.

Ordinary workers, whether at marinas or on board the yachts, are the ones who are losing out.

Revenue at the iconic marina in Saint-Tropez has…fallen by 30 percent since the beginning of the year, while Toulon, a less glamorous destination, has suffered a 40 percent decline. …They stated that refueling a 42-meter yacht in Italy (instead of France) “gives a saving of nearly €21,000 a week because of the difference in tax.” Sales by the four largest marine fuel vendors has fallen by 50 percent this summer, the letter said, adding that French “yachties”—an inexperienced 19-year-old deckhand makes around €2,000 per month and a good Captain can command €300,000—were being laid off in droves, as, due to the new tax rules, national insurance, health and other compulsory contributions which boat owners pay for crew members have increased from 15 to 55 percent of their wages. The letter stated that “the additional cost of maintaining a seven-person crew in France is €300,000 (£268,000) a year.”

All of this is – or should have been – totally predictable.

French tax authorities should have learned from what happened a few years ago in Italy.

Or from what happened in France a few decades ago.

…the French have been down this avenue before. “It happened in France about 30 years ago, so people moved their boats to Italy… Yachting is huge revenue earner for the region. …we contribute huge sums in social security alone. “But the bigger issue is that people holidaying on yachts here go ashore and spend money—and a lot of it.” Says Heslin: “The possibility of this happening if taxes and fees were increased has actually been talked about for the last two years, and everyone warned what would happen. “But this where the French government so often goes wrong, this attitude of, ‘Well, we are France, people will always come here.’” This time, it appears, they have called it wrong. Edmiston says, “Yachting is very important to local economy, but if people are not made to feel welcome here, there are plenty of other places where they will be.”

Incidentally, we have similar examples of counterproductive class warfare in the United States. Florida politicians shot themselves in the foot a number of years ago with high taxes on yachts.

And the luxury tax on yachts, which was part of President George H.W. Bush’s disastrous tax-hike deal in 1990, hurt middle-class boat builders much more than upper-income boat buyers.

But let’s zoom out and make a broader point about public finance and tax policy.

Harsh taxes on yachts backfire because the people being targeted have considerable ability to escape the tax by simply choosing to buy yachts, staff yachts, and sail yachts where taxes aren’t so onerous.

Let’s now apply this insight to something far more important than yachts.

Investment is a key for long-run growth and higher living standards. All economic theories – even Marxism ans socialism – agree that capital formation is necessary to increase productivity and thus boost wages.

Yet people don’t have to save and invest. They can choose to immediately enjoy their earnings, especially if there are harsh taxes on income that is saved and invested.

Or they can choose to (mis)allocate capital in ways that make sense from a tax perspective, but might not be very beneficial for the economy.

And upper-income taxpayers have a lot of latitude over how much of their money is saved and invested, as well as how it is saved and invested.

So when politicians impose high taxes on income that is saved and invested, they can expect big supply-side responses, just as there are big responses when they impose punitive taxes on yachts.

But here’s the bottom line. When they over-tax yachts, the damage isn’t that great. Yes, some local workers are out of jobs, but that tends to be offset by more job creation in other jurisdictions that now have more business from big boats.

Over-taxing saving and investment, by contrast, can permanently lower a nation’s prosperity by reducing capital formation. And to the extent that this policy is imposed on the entire world (which is basically what the OECD is seeking), then there’s no additional growth in other jurisdictions to offset the suffering caused by bad tax policy in one jurisdiction.