Both the House and Senate have approved reasonably good tax reform plans.

Lawmakers are now in a “conference committee” to iron out the differences between the two bills so that a consensus package can be a approved and sent to the White House for the President’s signature.

Sounds like we’re on the verge of getting a less-destructive tax system, right?

I hope so, but there are still some major hurdles. The conference committee has a difficult task.  They’re only allowed $1.5 trillion in tax relief in the short run and have to produce a bill that is “revenue neutral” in the long run. That won’t be easy in an environment where interest groups are putting heavy pressure on lawmakers.

They’re only allowed $1.5 trillion in tax relief in the short run and have to produce a bill that is “revenue neutral” in the long run. That won’t be easy in an environment where interest groups are putting heavy pressure on lawmakers.

I joked that doing tax reform with these restrictions is like trying to fit an NFL lineman in Pee Wee Herman’s clothes. But the serious point is that genuine tax reform requires some revenue-raising provisions to offset the parts of the bill that reduce revenue.

Needless to say, the right way of doing this is by going after economically harmful tax preferences. I’ve already written (over and over and over again) that the deduction for state and local taxes should be on the chopping block. To their credit, lawmakers are curtailing that loophole.

Today, I want to make the case that housing preferences in the tax code also should be targeted. I’m not naive enough to think politicians are suddenly going to decide to eliminate the mortgage interest deduction. But the bills – especially the House version – slightly curtail preferences for housing and it would be nice if they went a bit further.

That would free up more revenue for pro-growth tax cuts and also be smart policy. Let’s look at what some expert voices, starting with market-oriented people.

Edward Pinto of the American Enterprise Institute explains the provisions in the House bill for the Wall Street Journal.

Tax reform could make housing more affordable. Done correctly, it could increase the supply of homes by reducing federal tax subsidies for homeownership. The House’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act furthers this aim in several ways—by raising the standard deduction, capping new loans qualifying for the mortgage-interest deduction at $500,000, eliminating the deduction on loans for second homes and the deduction on cashing out home equity, and capping the property-tax deduction at $10,000.

The Senate bill raises the standard deduction as well, but otherwise basically gives housing a pass. In the conference committee, Senators should agree to the House approach. Pinto explains that homeownership will be higher with less “help” from Washington.

…the House tax bill would create about 870,000 additional available units over 10 years. This represents a boost of 14% (the current build rate will yield about 6.2 million units over 10 years). Cutting homeowner subsidies out of the tax code provides other important benefits. The percentage of mortgage holders who itemize would drop from about 60% to 12%.

This would free nearly half of mortgaged homeowners from a massive federal tax incentive hanging over their financial decisions, thereby greatly reducing the market-distorting impact produced by the interest deduction. …Lower prices due to loss of subsidies will ultimately allow more low-wealth Americans to become homeowners, since less cash will be needed to close a purchase. Rents will remain roughly constant as house prices decline, thus reducing the cost of homeownership compared with renting—another positive outcome. …It is time to put the interests of taxpayers and aspiring homeowners ahead of the interests of the housing lobby. Tax reform—especially if the final bill fully implements the House’s subsidy cuts—will improve the housing market and make homeownership more accessible to all.

Professor Jeffrey Dorfman of the University of Georgia (home of the national championship-bound Bulldogs, I can’t resist pointing out) discusses the issue in Forbes.

About 64% of Americans own a house. Roughly two-thirds of those homeowners have a mortgage. Only 6% of all mortgages are for $500,000 or more. Put all those numbers together and you will find that home builders and realtors think their world is ending over policy changes to the mortgage interest deduction that impact only about 2.5% of American households.

Plus, existing mortgages are grandfathered in, so anyone who purchased a home expecting the deduction will continue to enjoy it. …doubling the standard deduction means fewer people will itemize, meaning fewer will use the mortgage interest deduction. Importantly, those households that stop itemizing are doing so because the newly enlarged standard deduction provides them a lower tax burden. Households that have more after-tax income have more money to spend on houses, mortgage payments, and everything else in the economy. Housing is not being made unaffordable by the proposed tax reform since the vast majority of Americans will receive a moderate tax cut under the plan. Home builders and realtors seem concerned that a few rich Americans might not buy as expensive houses without as big a tax break, even though they will have more disposable income. …Housing depends much more on disposable income, the health of the job market, and Americans’ confidence in the economic future than it does on tax breaks. Don’t listen to the real estate industry; they will be just fine if the Tax Cut and Jobs Act passes.

George Will is not a fan of housing preferences in the tax code.

…only around 30 percent of taxpayers itemize their deductions. …not even half of all homeowners use the deduction. …the unpleasantness of 2008 demonstrated the downside of encouraging too much homeownership.

Furthermore, the deduction might actually suppress homeownership by being priced into rising housing costs. Besides, Australia, Canada and Britain, which have no mortgage interest deductions, have homeownership rates comparable to that of the United States. …Homeownership is…not an investment because “it does not improve the productive capacity of the economy.” Indeed, the more money that flows into housing, the less flows into stocks, bonds or banks.

Amen. We should have learned from 2008 that it’s bad news for government to muck around in housing.

Yet some politicians can’t resist because of their desire to buy votes.

Kevin Williamson of National Review adds his two cents.

It’s time for…a proposal to reduce or eliminate the mortgage-interest deduction, a tax subsidy that makes having a big mortgage on an expensive house relatively attractive to affluent households… Do not hold your breath waiting for the inequality warriors to congratulate Republicans for proposing…significant tax increases on the rich. …Slate economics editor Jordan Weissmann, who is not exactly Grover Norquist on the question of taxes, describes the mortgage-interest deduction as “an objectively horrible piece of public policy that should be reformed,” and it is difficult to disagree with him.

It distorts the housing market in favor of higher prices, which is great if you are old and rich and own a house or three like Bernie Sanders but stinks if you are young and strapped and looking to buy a house. It encourages buyers to take on more debt at higher interest rates than they probably would without the deduction, and almost all of the benefits go to well-off households in the top income quintile. It is the classic example of upper-class welfare. …mortgage subsidies are not randomly distributed. The mortgage-interest deduction is much more important to rich people in San Francisco, where the median home price exceeds $1 million, than it is to middle-class people in Tulsa, where the median home price is about $110,000. …The best course of action would be to eliminate the mortgage-interest deduction entirely over a relatively short period of time, say five years. …it is difficult to make a compelling case that subsidizing Lena Dunham’s mortgage on her $5 million Brooklyn apartment (or helping out whoever took that $4.2 million Trump apartment off Keith Olbermann’s hands) needs to be a top national policy priority.

Writing for the City Journal, Howard Husock explains why the deduction is bad policy.

…the deduction should be pruned or eliminated—not just because it is inequitable but also because it distorts the housing market. Currently, a taxpayer can deduct interest on a mortgage up to $1.1 million—substantially more than the median U.S. home value ($203,000). Not surprisingly, the Government Accountability Office has found that higher-income households are generally more likely to use the mortgage-interest and property-tax deductions. In 2008, the most recent tax year for which data are available, taxpayers with adjusted gross incomes of $100,000 or more “accounted for 13 percent of all returns but claimed nearly half (47 percent) of all mortgage interest and property tax deductions.” …The core problem with the MID, though, lies in how it affects housing markets. Inevitably, any policy that provides a tax reduction for those who buy or own homes increases the price of housing, through the implicit promise that the tax code will lower the effective house payments. MID supporters say that it encourages homeownership, but the Urban Institute finds that it mostly “rewards affluent households who would have bought homes anyway,” …Not surprisingly, the homebuilders lobby—among the hardiest of Washington swamp creatures—is fighting the proposal. …Reducing tax deductions that put the U.S. at a competitive disadvantage should not be impeded by a special-interest group that has achieved its purported social goal—homeownership—in the U.S. at a rate (64 percent) that lags that of Canada (67 percent), where mortgage interest is not deductible.

Even folks on the left realize that housing preferences are bad policy.

Here are some excerpts from a Slate column.

It also must be said that the mortgage interest deduction is an objectively horrible piece of public policy that should be reformed. Currently, it’s an estimated $80 billion-plus subsidy that disproportionately helps upper-middle-class and wealthy households—according to the Tax Policy Center, 72 percent of its benefits go to the highest-earning 20 percent of taxpayers. This is to be expected, since wealthier people can buy larger houses and take out bigger mortgages. It also explains much of its political invulnerability; people who earn low- to mid-six-figures vote and very much treasure their slice of the welfare state that’s submerged in our tax code. But as a result, the deduction mostly encourages people who could have afforded homes anyway to buy bigger. Research has shown it does little if anything to expand homeownership overall, and may actually discourage it among younger American by driving up prices.

Derek Thompson of the Atlantic points out that housing preferences are a reverse from of class warfare.

Although about two-thirds of American households own a home, only one-quarter of them claim the deduction…households earning more than $100,000 receive almost 90 percent of the benefits. …it makes it harder for poor renters to join the class of homeowners. …Desmond writes, “a 15-story public housing tower and a mortgaged suburban home are both government-subsidized, but only one looks (and feels) that way.”

Scholars also find he deduction is not good policy.

A just-released academic study confirms that the right kind of tax reform will be very good for society, the economy, and homeownership.

The model demonstrates that repealing the regressive mortgage interest deduction decreases housing consumption by the wealthy, increases aggregate homeownership, improves overall welfare, and leads to a decline in aggregate mortgage debt. The mechanisms behind these results are intuitive. When both house prices and rents are allowed to adjust, the repeal of the mortgage interest deduction decreases house prices because, ceteris paribus,

the after-tax cost of occupying a square foot of housing has risen. Reduced house prices allow low wealth, credit-constrained households to become homeowners because the minimum down payment required to purchase a house falls. At the same time, the elimination of the tax favored status of mortgages, acting in concert with the fall in equilibrium house prices, causes unconstrained households to reduce their mortgage debt. Because rents remain roughly constant as house prices decline, homeownership becomes cheaper relative to renting, which further re-enforces the positive effect of eliminating the mortgage interest deduction on homeownership. Importantly, the expected lifetime welfare of a newborn household rises because the tax reform shifts housing consumption from high income households (the main beneficiaries of the tax subsidy in its current form) to lower income families for whom the additional shelter consumption is relatively more valuable.

Now let’s look at experts who have strong arguments against the deduction, but who also comment on the distasteful role of special interests.

Matt Mitchell and Tad DeHaven, in a column for U.S. News & World Report, point out that the only real beneficiary of the deduction are interest groups (I call them swamp creatures) that want homeowners to go into debt in order to spend more money.

Motivated in part by a need to find revenue offsets for its broader tax cut proposal, the House has proposed to reduce the amount of mortgage debt taxpayers may deduct interest on from $1.1 million to $500,000; the Senate version would slightly reduce it to $1 million. But even these modest reforms have raised the ire of Big Housing. Indeed, even if both chambers had proposed to leave the mortgage interest deduction alone, this powerful lobby would still be upset that Congressional Republicans intend to raise the standard deduction: Doing so would cause fewer taxpayers to itemize, which means fewer people would claim the deduction. … the mortgage interest tax deduction…benefits wealthier Americans and the housing lobby at the expense of the majority of taxpayers, who receive no benefit…even the benefit for wealthier taxpayers is illusory “because the tax gains to homeowners are largely offset by increases in home prices.” That leaves the powerful housing lobby – represented most prominently by the National Association of Realtors and National Association of Homebuilders – as the real beneficiary. …why, then, has Big Housing fought so hard to keep the mortgage interest deduction? The answer is that although the deduction doesn’t affect home ownership, it does incentivize people to purchase more expensive homes. That translates into more money for realtors and home builders. And because the deduction is taken against the interest payment and not the down payment, it encourages home buyers to put more of the purchase on credit. So in reality, the deduction encourages home-borrowship, not homeownership. Did we mention that the Mortgage Bankers Association is also a prominent defender of the mortgage interest deduction?

Since we’re on the topic of swamp creatures, Tim Carney of the Washington Examiner explains that housing preferences are bad for families and good for interest groups.

That means a married couple who rents (or owns a modest house, say, less than $225,000) making $70,000 would probably see their federal income taxes fall by 25 percent. Some lower-income families — including homeowners — would have their federal income tax liability wiped out. Middle-class families who currently itemize their deductions (because they spend more $12,600 a year on mortgage interest and charitable giving) would have their taxes go down, and their tax-filing simplified. …Will this lower home prices? Probably yes, because the value of this deduction gets priced into homes. That is, this deduction wasn’t really helping homeowners anyway. Who was the deduction helping? Mortgage lenders and homebuilders mostly, also realtors. These are the special interests who created and who fight tirelessly to save this deduction. Removing an economic distortion that has inflated home prices will create some losers, sure, but that doesn’t make it bad. Inflated home prices have stultified mobility, delayed family formation, increased household debt, and otherwise tied up families’ assets.

Tom Giovanetti of the Institute for Policy Innovation also criticizes the interest groups defending special preferences.

One of the obstacles to fundamental tax reform has always been that there is an entrenched constituency that benefits in some way from every provision in the tax code, and that can be counted on to noisily oppose any change to it. These constituencies are often not taxpayers themselves but business interests that have built a business on a particular tax provision.

An obvious example is the residential mortgage interest deduction. …current tax reform plans would increase the standard deduction available to taxpayers who choose not to itemize their deductions. In other words, the real estate industry has a targeted tax preference that is only available to home owners through the itemized deduction, and they don’t want to see that tax preference diluted by a higher standard deduction available to everyone else. This is an obnoxious argument for the real estate industry to be making. Giving a higher standard deduction to those who do not itemize doesn’t take anything away from taxpayers who do, and it would simplify tax filing for many taxpayers because it would make the standard deduction more attractive. Apparently the real estate industry doesn’t want Americans to get a tax break unless they agree to go into massive debt to buy a house.

The Wall Street Journal also opined about the odious role of interest groups.

…doubling the standard deduction…would make the first $24,000 of income for a married couple tax-free. What’s not to like? Plenty, says the housing lobby. The National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB) and the National Association of Realtors each bashed the larger standard deduction on grounds that it would make the tax subsidy to their industries less appealing. …a reminder of how misguided the mortgage-interest deduction is. For starters, it distorts the allocation of capital by favoring housing,

a form of consumption, over investments that might be more productive and raise everyone’s living standards. The deduction also disproportionately benefits the affluent, who buy more expensive homes with bigger mortgages. A 2013 Congressional Budget Office study found that 75% of the benefit of the mortgage-interest deduction goes to the top 20% of income earners. Two of three American tax filers don’t even itemize, which means they can’t deduct mortgage interest even if they have it. It’s also not clear the mortgage deduction is as critical to home ownership as advocates contend. Canada and Britain have similar rates of home ownership as the U.S. (nearly two thirds of their citizens) without a mortgage-interest deduction. …Republicans should reconsider giving housing a pass. For example, the GOP could limit the amount of mortgage-interest that could be deducted, or limit the deduction to borrowing below, say, $250,000. This would make the tax benefit less tilted to the affluent, and it would also provide more revenue for lower tax rates.

Since the WSJ editorial mentions that Canada has very high homeownership without any loopholes, let’s close today’s column by reviewing some additional global evidence.

In a chapter for a book on tax reform, Bill Gale of Brookings points out that the U.K. dramatically curtailed the tax benefit of housing without any adverse impact on homeownership.

Great Britain conducted a fascinating experiment showing both the political and economic viability of reducing mortgage subsidies.’ When tax subsidies for most forms of borrowing were eliminated in 1974-1975, subsidies for interest on the principal primary residence were retained, subject to a loan limit of £25,000. No subsidies were provided on second homes. The limit was raised to £30,000 in 1983-1984 and has stayed fixed since.

…More recently, the subsidy has been provided only up to a fixed rate, set at 25 percent and then reduced to 15 percent for new loans in 1998. The British experience raises several interesting possibilities. …because the £30,000 limit is well below the average new mortgage loan, mortgage subsidies provide no marginal incentive for most taxpayers. …the decline in the value of the mortgage interest subsidy has been gradual, but huge. From 1974 to 1996, the value-thought of as the interest rate times the rate at which the subsidy is taken times the real loan limit-fell by about 90 percent. Nevertheless, finding much of an effect of the policies on the housing sector is difficult. From 1974 to 1994, homeownership rates, the ratio of mortgage debt to GDP, the ratio of mortgage debt to the housing stock, and the ratio of housing to fixed capital rose faster in the United Kingdom than in the United States. …the significant reduction in mortgage subsidies when homeownership rates were rising (by thirteen percentage points from 1974 to 1994) may make the events even more remarkable from a political perspective. The British experience and cross-country evidence that the presence of a deduction for mortgage interest does not greatly influence homeownership rates suggest that the value of subsidies for owner-occupied housing could be reduced.

Charles Hughes of the Manhattan Institute writes about the deduction’s downsides, but the part of his article that I want to highlight is the description of how Denmark curtailed housing preferences with no adverse consequences.

Many areas in the tax code introduce substantial distortions that are ripe for reform. One area is the mortgage interest deduction (MID), which allows claimants to deduct mortgage interest on their primary or secondary residences, up to a certain threshold.

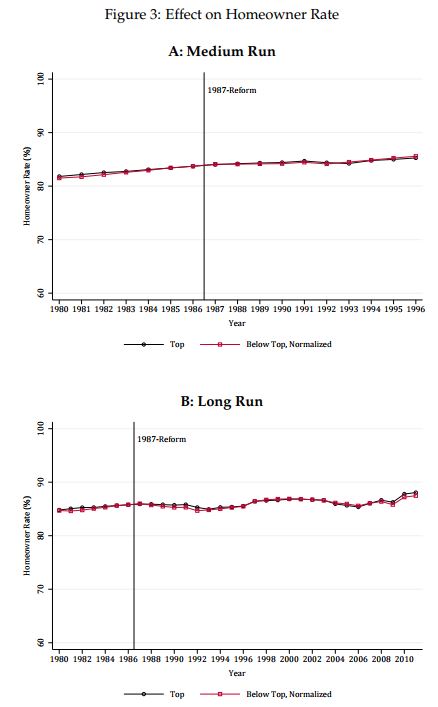

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the deduction for mortgage interest will reduce revenue by $72.4 billion this year, and by $234 billion through 2020, making it one of the most expensive tax expenditures in the tax code. Even at this magnitude, only about a quarter of tax filers claim the deduction… A new working paper analyzing the effects of the mortgage interest deduction in Denmark finds that it has no effect on homeownership rates in the long run, and it distorts decision-making about the size and price of which homes to buy. …the economists found no short- or long-run effects on home ownership.

Here’s a chart from that study. As you can see, dramatically curtailing the value of the deduction for mortgage interest did not have any noticeable impact on homeownership.

P.S. If you like the gory details of tax policy, I explained in 2012 that the problem with the tax code and housing isn’t the mortgage interest deduction, per se, but rather the fact that business investment doesn’t get the same treatment as residential real estate.

P.P.S. While lawmakers are debating whether to slightly limit preferences for housing, I should point out that there are two other huge loopholes – the municipal bond interest exemption and the healthcare exclusion – that basically were left untouched. Hopefully, they will be on the chopping block for the next installment of tax reform.