I’ve been arguing all year that a substantially lower corporate tax rate is the most vital goal of tax reform for reasons of competitiveness.

And I continued to beat that drum in an interview last week with Fox Business.

The Wall Street Journal agrees that the time has come for a lower corporate rate. Unless, of course, one would prefer the United States to fall even further behind other countries.

President Emmanuel Macron last week pushed a budget featuring substantial tax relief through the National Assembly. The top rate on corporate profits will fall to 28% by 2020 from 33.33% today, and Mr. Macron has promised 25% by 2022. …Critics branded Mr. Macron “the President for the rich” for these overhauls, but the main effect will be to stimulate investment and job creation… The Netherlands also is jumping on the bandwagon. Prime Minister Mark Rutte promises to cut the top corporate rate to 21% from 25% by 2021… Do American politicians really want to have to explain to voters why they let the U.S. trail even France?

For the most part, opponents of tax reform in the United States understand that they have lost the competitiveness argument. So they will pay lip service to the notion that a lower corporate rate is desirable (heck, even Obama notionally agreed), but they will fret about the loss of tax revenue and a supposed windfall for the “rich.”

I agree that tax revenues will decrease, at least in the short run. But there’s some very good research showing the long-run revenue-maximizing corporate rate is somewhere between 15 percent and 25 percent.

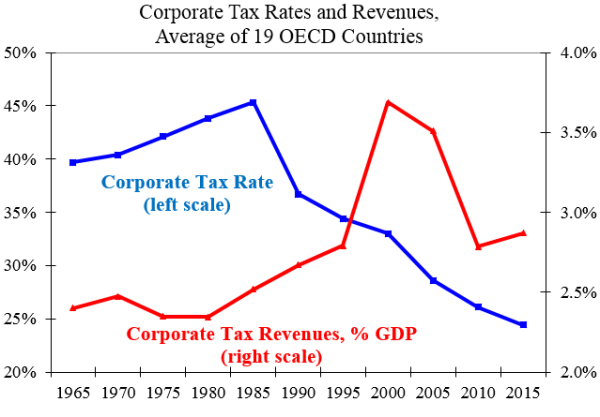

And Chris Edwards of the Cato Institute reviewed fifty years of data for industrialized nations and ascertained that lower tax rates are associated with rising revenue.

There’s also good evidence from Canada and the United Kingdom if you want country-specific examples of the relationship between corporate tax rates and corporate tax revenue.

By the way, even left-leaning multilateral bureaucracies such as the International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have published research showing the same thing.

And what about the debate over whether the “rich” benefit?

That issue is a red herring. Yes, shareholders of companies, on average, have higher incomes, and they will benefit if the rate is reduced, but I’ve never been motivated by animosity against those with more money (assuming they earned their money rather than mooching off the government).

What does get my juices flowing, however, is growth. And if we can get more dynamism in the economy, that translates into more jobs and higher income.

A new report from the Council of Economic Advisers estimates the potential benefit for ordinary people.

Reducing the statutory federal corporate tax rate from 35 to 20 percent would, the analysis below suggests, increase average household income in the United States by, very conservatively, $4,000 annually. …Moreover, the broad range of results in the literature suggest that over a decade, this effect could be much larger.

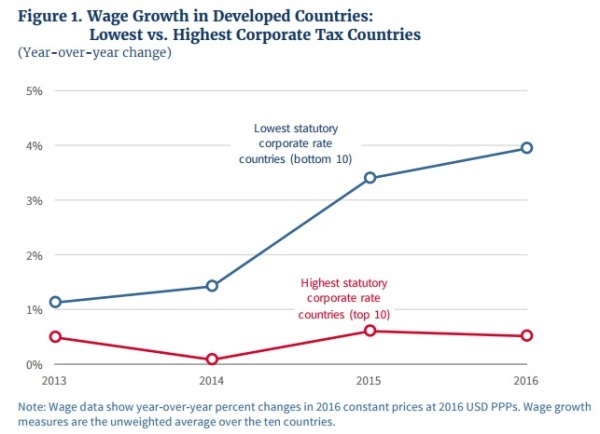

There’s some good cross-country data showing nations with lower corporate tax rates do better.

Between 2012 and 2016, the 10 lowest corporate tax countries of the OECD had corporate tax rates 13.9 percentage points lower than the 10 highest corporate tax countries, about the same scale as the reduction currently under consideration in the U.S. The average wage growth in the low tax countries has been dramatically higher.

Here’s the accompanying chart.

As you can see, there’s a clear divergence between higher-tax and lower-tax nations. Though, given the limited time period in the chart and the fact that many other factors can impact wage growth, I’m actually more persuaded by some of the other empirical research cited in the CEA report.

Arulpalapam et al (2012) find that workers pay nearly 50 percent of the tax, while Desai et al (2007) estimate a worker share of 45 to 75 percent. Gravelle and Smetters (2006) generate a rate of 21 percent when the rate of capital mobility across countries is moderate and 73 percent when capital can flow freely, evidence that the labor incidence is likely both dynamic and positively correlated with the rate of international capital transfers. A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) study (Randolph, 2006) finds that workers bear 70 percent of the corporate income tax burden in the baseline and 59 to 91 percent in alternative specifications. In a summary study, Jensen and Mathur (2011) argue for an assumption of greater than 50 percent. …A cross-country study by Hassett and Mathur (2006) based on 65 countries and 25 years of data finds that the elasticity of worker wages in manufacturing after five years with respect to the highest marginal tax rate in a country is as low as -1.0 in some specifications, although other sets of control variables increase the elasticity to -0.3. Expanded analysis by Felix (2007) follows the Hassett and Mathur strategy, but incorporates additional control variables, including worker education levels. Felix settles on an elasticity of worker wages with respect to corporate income taxes of -0.4, at the high end of the Hassett and Mathur range. …Felix (2009) estimates an elasticity of worker wages with respect to corporate income tax rates based on variation in the marginal tax rate across U.S. states. In this case, the elasticity is substantially lower; a 1 percentage point increase in the top marginal state corporate rate reduces gross wages by 0.14 to 0.36 percent over the entire period (1977-2005) and by up to 0.45 percent for the most recent period in her data (2000-2005). …Desai et al (2007)…measure both the changes in worker wages and changes in capital income associated with corporate income tax changes. The estimated labor burden of the corporate tax rate varies from 45 to 75 percent under various specifications in the paper.

That’s a lot of jargon, so I suspect that many readers will find data from Germany and Australia to be more useful when considering how workers benefit from lower corporate rates.

P.S. While I think a lower corporate tax rate may result in more revenue over time, that’s definitely not my goal.

P.P.S. The biggest obstacle to good tax policy is the unwillingness of Republicans to impose even a modest amount of spending restraint.

———

Image credit: geralt | Pixabay License.