I wrote yesterday to praise the Better Way tax plan put forth by House Republicans, but I added a very important caveat: The “destination-based” nature of the revised corporate income tax could be a poison pill for reform.

I listed five concerns about a so-called destination-based cash flow tax (DBCFT), most notably my concerns that it would undermine tax competition![]() (folks on the left think it creates a “race to the bottom” when governments have to compete with each other) and also that it could (because of international trade treaties) be an inadvertent stepping stone for a government-expanding value-added tax.

(folks on the left think it creates a “race to the bottom” when governments have to compete with each other) and also that it could (because of international trade treaties) be an inadvertent stepping stone for a government-expanding value-added tax.

CF&P’s Brian Garst has just authored a new study on the DBCFT. Here’s his summary description of the tax.

The DBCFT would be a new type of corporate income tax that disallows any deductions for imports while also exempting export-related revenue from taxation. This mercantilist system is based on the same “destination” principle as European value-added taxes, which means that it is explicitly designed to preclude tax competition.

Since CF&P was created to protect and promote tax competition, you won’t be surprised to learn that the DBCFT’s anti-tax competition structure is a primary objection to this new tax.

First, the DBCFT is likely to grow government in the long-run due to its weakening of international tax competition and the loss of its disciplinary impact on political behavior. … Tax competition works because assets are mobile. This provides pressure on politicians to keep rates from climbing too high. When the tax base shifts heavily toward immobile economic activity, such competition is dramatically weakened. This is cited as a benefit of the tax by those seeking higher and more progressive rates. …Alan Auerbach, touts that the DBCFT “alleviates the pressure to reduce the corporate tax rate,” and that it would “alter fundamentally the terms of international tax competition.” This raises the obvious question—would those businesses and economists that favor the DBCFT at a 20% rate be so supportive at a higher rate?

Brian also shares my concern that the plan may morph into a VAT if the WTO ultimately decides that it violates trade rules.

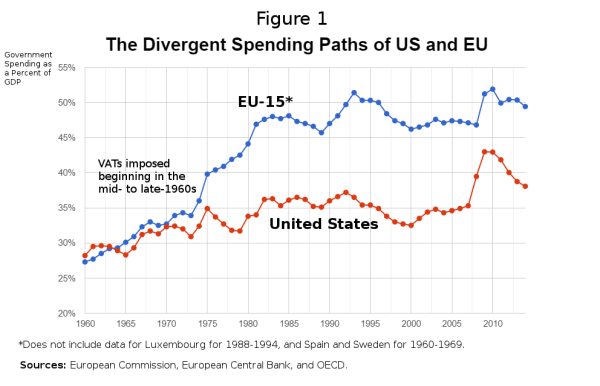

Second, the DBCFT almost certainly violates World Trade Organization commitments. …Unfortunately, it is quite possible that lawmakers will try to “fix” the tax by making it into an actual value-added tax rather than something that is merely based on the same anti-tax competition principles as European-style VATs. …the close similarity of the VAT and the DBCFT is worrisome… Before VATs were widely adopted, European nations featured similar levels of government spending as the United States… Feeding at least in part off the easy revenue generate by their VATs, European nations grew much more drastically over the last half century than the United States and now feature higher burdens of government spending. The lack of a VAT-like revenue engine in the U.S. constrained efforts to put the United States on a similar trajectory as European nations.

And if you’re wondering why a VAT would be a bad idea, here’s a chart from Brian’s paper showing how the burden of government spending in Europe increased once that tax was imposed.

In the new report, Brian elaborates on the downsides of a VAT.

If the DBCFT turns into a subtraction-method VAT, its costs would be further hidden from taxpayers. Workers would not easily understand that their employers were paying a big VAT withholding tax (in addition to withholding for income tax). This makes it easier for politicians to raise rates in the future. …Keep in mind that European nations have corporate income tax systems in addition to their onerous VAT regimes.

And he points out that those who support the DBCFT for protectionist reasons will be disappointed at the final outcome.

…if other nations were to follow suit and adopt a destination-based system as proponents suggest, it will mean more taxes on U.S. exports. Due to the resulting decline in competitive downward pressure on tax rates, the long-run result would be higher tax burdens across the board and a worse global economic environment.

Brian concludes with some advice for Republicans.

Lawmakers should always consider what is likely to happen once the other side eventually returns to power, especially when they embark upon politically risky endeavors… In this case, left-leaning politicians would see the DBCFT not as something to be undone, but as a jumping off point for new and higher taxes. A highly probable outcome is that the United States’ corporate tax environment becomes more like that of Europe, consisting of both consumption and income taxes. The long-run consequences will thus be the opposite of what today’s lawmakers hope to achieve. Instead of a less destructive tax code, the eventual result could be bigger government, higher taxes, and slower economic growth.

Amen.

My concern with the DBCFT is partly based on theoretical objections, but what really motivates me is that I don’t want to accidentally or inadvertently help statists expand the size and scope of government. And that will happen if we undermine tax competition and/or set in motion events that could lead to a value-added tax.

Let’s close with three hopefully helpful observations.

Helpful Reminder #1: Congressional supporters want a destination-based system as a “pay for” to help finance pro-growth tax reforms, but they should keep in mind that leftists want a destination-based system for bad reasons.

Based on dozens of conversations, I think it’s fair to say that the supporters of the Better Way plan don’t have strong feelings for destination-based taxation as an economic principle. Instead, they simply chose that approach because it is projected to generate $1.2 trillion of revenue and they want to use that money to “pay for” the good tax cuts in the overall plan.

That’s a legitimate choice. But they also should keep in mind why other people prefer that approach. Folks on the left want a destination-based tax system because they don’t like tax competition. They understand that tax competition restrains the ability of governments to over-tax and over-spend. Governments in Europe chose destination-based value-added taxes to prevent consumers from being able to buy goods and services where VAT rates are lower. In other words, to neuter tax competition. Some state governments with high sales taxes in the United States are pushing a destination-based system for sales taxes because they want to hinder consumers from buying goods and services from states with low (or no) sales taxes. Again, their goal is to cripple tax competition.

Something else to keep in mind is that leftist supporters of the DBCFT also presumably see the plan as being a big step toward achieving a value-added tax, which they support as the most effective way of enabling bigger government in the United States.

Helpful Reminder #2: Choosing the right tax base (i.e., taxing income only one time, otherwise known as a consumption-base system) does not require choosing a destination-based approach.

The proponents of the Better Way plan want a “consumption-base” tax. This is a worthy goal. After all, that principle means a system where economic activity is taxed only one time. But that choice is completely independent of the decision whether the tax system should be “origin-based” or “destination-based.”

The gold standard of tax reform has always been the Hall-Rabushka flat tax, which is a consumption-base tax because there is no double taxation of income that is saved and invested. It also is an “origin-based” tax because economic activity is taxed (only one time!) where income is earned rather than where income is consumed.

The bottom line is that you can have the right tax base with either an origin-based system or a destination-based system.

Helpful Reminder #3: The good reforms of the Better Way plan can be achieved without the downside risks of a destination-based tax system.

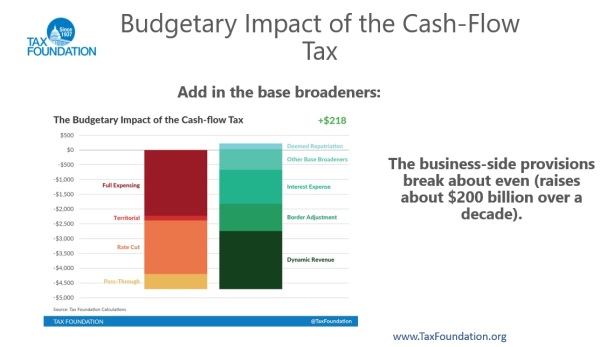

The Tax Foundation, even in rare instances when I disagree with its conclusions, always does very good work. And they are the go-to place for estimates of how policy changes will affect tax receipts and the economy. Here is a chart with their estimates of the revenue impact of various changes to business taxation in the Better Way plan. As you can see, the switch to a destination-based system (“border adjustment”) pulls in about $1.2 trillion over 10 years. And you can also see all the good reforms (expensing, rate reduction, etc) that are being financed with the various “pay fors” in the plan.

I am constantly asked how the numbers can work if “border adjustment” is removed from the plan. That’s a very fair question.

But there are lots of potential answers, including:

- Make a virtue out of necessity by reducing government revenue by $1.2 trillion.

- Reduce the growth of government spending to generate offsetting savings.

- Find other “pay fors” in the tax code (my first choice would be the healthcare exclusion).

- Reduce the size of the tax cuts in the Better Way plan by $1.2 trillion.

I’m not pretending that any of these options are politically easy. If they were, the drafters of the Better Way plan probably would have picked them already. But I am suggesting that any of those options would be better than adopting a destination-based system for business taxation.

Ultimately, the debate over the DBCFT is about how different people assess political risks. House Republicans advocating the plan want good things, and they obviously think the downside risks in the future are outweighed by the ability to finance a larger level of good tax reforms today. Skeptics appreciate that those proponents want good policy, but we worry about the long-run consequences of changes that may (especially when the left sooner or late regains control) enable bigger government.

P.S. This is not the first time that advocates of good policy have bickered with each other. During the 2016 nomination battle, Rand Paul and Ted Cruz plans proposed tax reform plans that fixed many of the bad problems in the tax code. But they financed some of those changes by including value-added taxes in their plans. In the short run, either plan would have been much better than the current system. But I was critical because I worried the inclusion of VATs would eventually give statists a tool to further increase the burden of government.