When I give speeches about the economic case for small government, one of my main points is that people in the private sector (workers, investors, managers, entrepreneurs, etc) are motivated by self interest to allocate labor and capital efficiently. To be more specific, the pursuit of higher pay and greater profit will lead people to allocate resources productively.

I freely admit that people in the private sector make mistakes (most new business ventures ultimately fail, for instance), but I explain that’s part of a dynamic process in a market economy. Every success and every mistake leads to feedback, both via the price system and also via profits and losses. All of which leads to continuous changes as people – especially entrepreneurs – seek to better serve the needs and wants of consumers, since that’s how they can increase their income and wealth.

I freely admit that people in the private sector make mistakes (most new business ventures ultimately fail, for instance), but I explain that’s part of a dynamic process in a market economy. Every success and every mistake leads to feedback, both via the price system and also via profits and losses. All of which leads to continuous changes as people – especially entrepreneurs – seek to better serve the needs and wants of consumers, since that’s how they can increase their income and wealth.

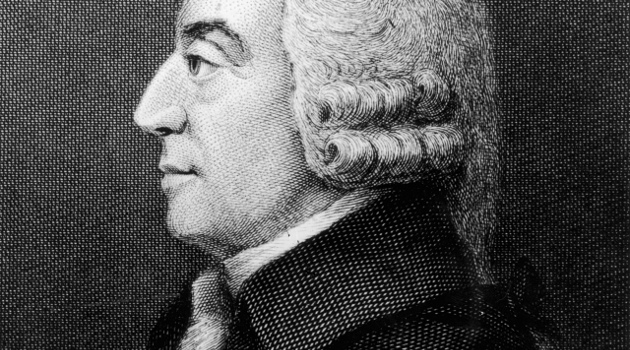

In other words, Adam Smith was right when he said that self-interest encourages people to focus on making others better off.

By contrast, when politicians and bureaucrats allocate resources (either directly via spending programs, or indirectly via regulation or tax distortions), feedback mechanisms are very weak. Once politicians intervene, they never seem to care if they are generating positive results. There are plenty of examples, however, of government imposing high costs while producing no benefits. Or even producing harm.

- Increased redistribution spending is associated with a halt in the historical progress against poverty.

- More education spending has completely failed to produce better education outcomes.

- More regulations and red tape to fight money launderinghaves not produced reductions in criminal activity.

- Foreign aid outlays that enable larger public sectors that undermine prosperity in developing nations.

And let’s not forget that “Public Choice” teaches us that interest groups will manipulate government to obtain unearned benefits.

The main lesson from all this information is that it’s good to have small government rather than large government.

But there’s a secondary lesson about how the economic harm of government can be reduced if market forces somehow can be part of the process. And that’s why a new study from two Italian economists at the Centre for Economic and International Studies is worth sharing.

The abstract of the study is a good summary.

We empirically investigate the effect of oversight on contract outcomes in public procurement. In particular, we stress a distinction between public and private oversight: the former is a set of bureaucratic checks enacted by contracting offices, while the latter is carried out by private insurance companies whose money is at stake through so-called surety bonding. We analyze the universe of U.S. federal contracts in the period 2005-2015 and exploit an exogenous variation in the threshold for both sources of oversight, estimating their causal effects on costs and execution time. We find that: (i) public oversight negatively affects outcomes, in particular for less competent buyers; (ii) private oversight has a positive effect on outcomes by affecting both the ex-ante screening of bidders – altering the pool of winning firms – and the ex-post behavior of contractors.

In other words, normal bureaucratic waste, featherbedding, and cost overruns are less likely when the private sector does the oversight.

And here’s an excerpt from the text for those who want more details.

…we propose a distinction between public and private oversight, depending on its source. Public oversight includes all formal checks – cost certifications, pricing data transmission, production surveillance – which the contracting authorities enact during the contract awarding phase and execution. It typically involves considerable paperwork for both the buyer and the sellers. At the cost of some red tape, it is aimed at alleviating the moral hazard problem… On the other hand, private oversight involves third parties – surety companies – issuing bonds (surety bonds) to secure the buyer against unpredictable events. If the seller fails to fulfill contractual tasks, contracting authorities make claims to recover losses. A surety is then called on either to complete the public work by themselves (i.e. with their own resources or by subcontracting) or to refund the authority of the bond value. Being liable in case of unsatisfactory contract outcomes, the sureties have strong incentives both to screen bidders (ex ante) and to monitor contractors (ex post). They help mitigate the asymmetry of information between the buyer and the sellers thanks to their experience of the market – i.e. access to private information – and the screening enacted through price discrimination on premia, which directly affects offers placed by potential contractors. Hence, private oversight enhances the selection of the best contractors and provides a second tier of monitoring of contractors’ progresses.

This is encouraging. It would be nice to have smaller government, but it also would be nice to get the most bang for the buck when the government does spend money.

To be sure, there are probably many parts of government that are impervious to market forces.

But surely there are many ways to protect taxpayers by creating incentives to save money.

- For instance, on the programmatic level, we can enlist the private sector to fight rampant Medicare and Medicaid fraud by allowing private investigators to keep a slice of any recovered funds.

- And on the sectoral level, we can achieve big educational gains with school choice, thus giving schools a bottom-line incentive to attract students with better outcomes.

- Last but not least, we can rely on the competitive impact of federalism to encourage better macroeconomic policy by state and local governments.

The moral of the story, needless to say, is that the private sector does a better job than government. So let’s do what we can to unleash market forces. Be more like Hong Kong and less like Venezuela.