There’s a lot to admire about Switzerland, particularly compared to its profligate neighbors.

- It has a spending cap, imposed in a landslide referendum early last decade, that has constrained the growth of government.

- It has a genuinely decentralized system with a very small central government and vigorous competition among cantons.

- There’s widespread gun ownership, and the number of guns owners keeps expanding.

- It has strong human rights laws protecting financial privacy (though unfortunately has been bullied into weakening protections for non-Swiss investors).

- It has comparatively modest tax rates and a relatively low level of redistribution.

With all these features, you won’t be surprised to learn that Switzerland is highly ranked by Human Freedom Index (#2), Economic Freedom of the World (#4), Index of Economic Freedom (#4), Global Competitiveness Report (#1), Tax Oppression Index (#1), and World Competitiveness Yearbook (#2).

Today let’s augment our list of good Swiss policies for reviewing the near-universal system of private pensions. I’ve been in Switzerland this week for a couple of speeches in Geneva, as well as interviews and meetings in Zurich and Bern.

As part of my travels around the country, I took the time to learn more about the “second pillar” of the country’s pension system.

Here’s a basic description from the Swiss government (with the help of Google translate).

The first pension funds were founded more than a hundred years ago… In 1972 the occupational pensions were included in the constitution. There it represents the second column in the three-column concept… The BVG compulsory scheme applies to all employees who are already insured in the first pillar… Pension provision in the second pillar is based on an individual savings process. This starts at 25 years. However, the condition is an annual income that exceeds the threshold (since 2015: 21’150 francs). The savings process ends with the reaching of the pension age. The accumulated savings in the individual account of the insured [are] used to finance the retirement pension.

If you want something in original English, here’s a brief description from the Swiss-American Chamber of Commerce.

The second pillar is governed by the provisions of the laws on occupational pension provision (BVG)… Employees who are paid by the same employer an annual salary exceeding CHF 21,150 are subject to compulsory insurance. The share of the salary which is subject to compulsory insurance is…between CHF 24,675 (the coordination deduction) and CHF 84,600… An employer who employs persons subject to compulsory insurance must be affiliated to a provident institution entered in the register for occupational benefit plan. The contributions into the pension scheme depend on age and include a minimum saving portion of 7% – 18% of the coordinated salary plus a risk portion. Both are equally shared between employer and employee. The benefits of the insured persons consist in the old age, invalidity and survivors pensions.

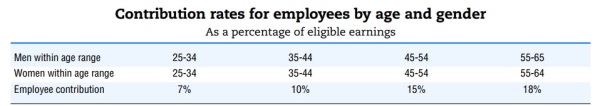

One of the interesting quirks of the system is that the mandatory contribution rate changes with age. The older you are, the more you pay.

I’m not sure that makes a lot of sense if the goal is for people to have big nest eggs when they retire, but nobody asked me. In any event, here’s a table showing the age-dependent contribution rates from an OECD description of the Swiss system.

Technically speaking, the contributions are evenly split between employees and employers, though labor economists widely agree that workers bear the real cost.

It’s also worth noting that the Swiss system is based on “defined contribution” like the Chilean and Australian private retirement systems. This means retirement income generally is a function of how much is saved and how well it is invested.

By contrast, the Dutch private system is based on “defined benefit,” which means that workers get a pre-determined level of retirement income. As evidenced by huge shortfalls in the defined benefit regimes maintained by many public and private employers in the United States, this approach is very risky if there aren’t high levels of integrity and honesty.

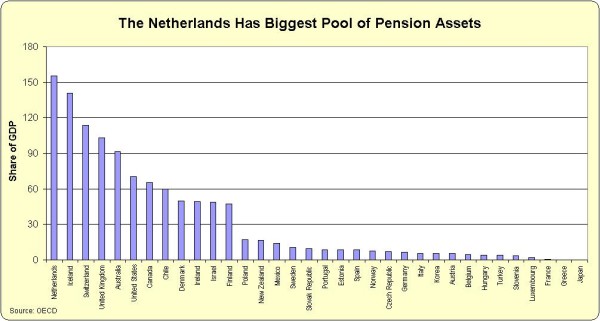

Though that doesn’t seem to be a problem in the Netherlands. Speaking of the Dutch system, here’s a chart I shared back in 2014.

It was designed to laud the Netherlands, but you can see that Switzerland also had a large pool of pension assets, equal to more than 110 percent of GDP (according to OECD data, now 123 percent of GDP).

Looking at this data, ask yourself whether Switzerland (or the Netherlands, Iceland, Australia, etc) will be in a stronger position to handle the fiscal challenge of aging populations, particularly when compared to nations with virtually no private pension assets, such as France, Greece, and Japan.

The Swiss regime certainly isn’t perfect, and neither are the systems in other nations with private retirement savings. But at least those nations are in much better shape to deal with future demographic changes. Workers in Switzerland and other countries with similar systems have real assets rather than unsustainable political promises. And it’s also worth pointing out that there are macroeconomic benefits for nations that rely more on private savings rather than tax-and-transfer entitlement schemes.

In other words, the Swiss system is much better than America’s bankrupt Social Security scheme.

P.S. Back in 2011, I compared five good features of the United States to five good features of Switzerland. If retirement systems were part of that discussion, Switzerland would have enjoyed a sixth advantage.

P.P.S. Switzerland does have some warts. It is only ranked #31 in the World Bank’s Doing Business. It also has a self-destructive wealth tax. And government spending, though modest compared to neighbors, consumes slightly more than one-third of economic output.