I’m currently in Tokyo for an Innovation Summit. Perhaps because I once referred to Japan as a basket case, I’ve been asked to speak about policies that are needed to boost the nation’s competitiveness.

That sounds like an easy topic since I can simply explain that free markets and small government are the universal recipe for growth and prosperity.

But then I figured I should be more focused and look at some of Japan’s specific challenges. So I began to ponder whether I should talk about Japan’s high debt levels. Or perhaps the country’s repeated (and failed) attempts to stimulate the economy with Keynesianism. And Japan’s demographic crisis is also a very important issue.

But then I figured I should be more focused and look at some of Japan’s specific challenges. So I began to ponder whether I should talk about Japan’s high debt levels. Or perhaps the country’s repeated (and failed) attempts to stimulate the economy with Keynesianism. And Japan’s demographic crisis is also a very important issue.

But since I only have 20 minutes (not even counting Q&A), I don’t really have time for a detailed examination on any of those topics. So I was still uncertain of how best to illustrate the need for pro-market reforms.

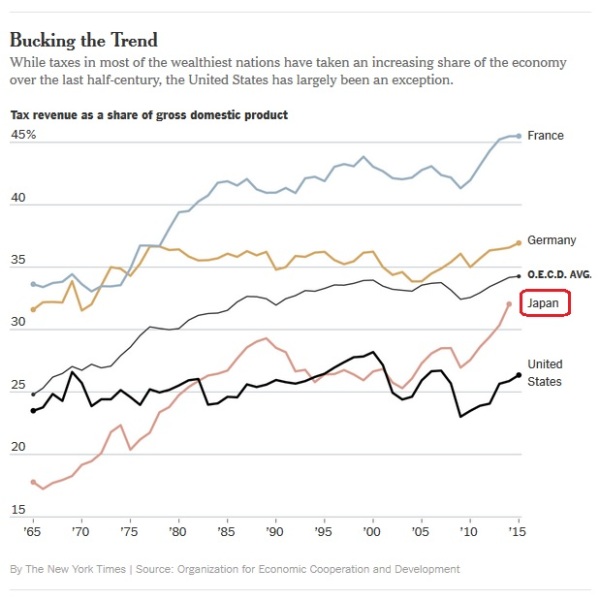

My job suddenly got a lot easier, though, because Eduardo Porter of the New York Times wrote a column today that includes a graph very effectively illustrating why Japan is in trouble. Simply stated, the country is on a very bad trajectory of ever-higher taxes.

To elaborate, Japan used to have a relatively modest tax burden, at least compared to other industrialized nations. But then, thanks in part to the enactment of a value-added tax, the aggregate tax burden began to climb. It has jumped from about 18 percent of economic output in 1965 to about 32 percent of gross domestic product in 2015.

Even the French didn’t raise taxes that dramatically!

By the way, I feel compelled to digress and point out that Mr. Porter’s column was not designed to warn about rising taxes in Japan. Instead, he was whining about non-rising taxes in the United States. I’m not joking.

American tax policy must stand as one of the great mysteries of the global political economy. In 1969…federal, state and local governments in the United States raised about the same in taxes, as a share of the economy, as the government of the average industrialized country: 26.6 percent of gross domestic product, against 27 percent among the nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Nearly 50 years later, the tax picture has changed little in the United States. By 2015, …the figure was 26.4 percent of G.D.P. But across the market democracies of the O.E.C.D., the share had climbed by an average of more than seven percentage points. …Americans are paying dearly as a result, as their comparatively small government has proved incapable of providing an adequate safety net…there is no credible evidence that countries with higher tax rates necessarily grow less.

Americans are “paying dearly”? Are we “paying dearly” because our living standards are so much higher? Are we “paying dearly” because our growth rates are higher and Europe is failing to converge? Are we “paying dearly” because America’s poorest states are rich compared to European countries.

Now that I got that off my chest, let’s get back to our discussion about Japan.

Looking at the data from Economic Freedom of the World, Japan ranked among the world’s 10-freest economies as recently as 1990. Today, it ranks #39. That is a very unfortunate development, though I should point out that the nation’s relative decline isn’t solely because of misguided fiscal policy.

I’ll close by noting that even the good news from Japan isn’t that good. Yes, the government did slightly lower its corporate tax rate so it no longer has the highest burden among developed nations. But having the second-highest corporate tax rate is hardly something to cheer about.

P.S. Since today’s column looks at the most depressing Japanese chart, I should remind people that I shared the most depressing Danish PowerPoint slide back in 2015. I may need to create a collection.

P.P.S. I doubt anyone will be surprised to learn that the OECD and IMF have been encouraging bad policy for Japan.

P.P.P.S. If I had to guess, I would say that Japan’s government is probably more competent than average. But that doesn’t mean it’s incapable of some bone-headed policies, such as a regulatory regime for coffee enemas and a giveaway program that was so convoluted that no companies asked for the free money.

———

Image credit: victorpalmer | Pixabay License.