Time for an update on the perpetual motion machine of Keynesian economics.

We’ll start with the good news. The Treasury Department commissioned a study on the efficacy of the so-called stimulus spending that took place at the end of last decade. As discussed in this news report, the results were negative.

…a scathing new Treasury-commissioned report…argues the cash splash actually weakened the economy and damaged local industry… The report, …says the…fiscal stimulus was “unnecessarily large” and “misconceived because it emphasised transfers, unproductive expenditure…rather than tax relief and/or supply side reform”.

The bad news, at least from an American perspective, is that it was this story isn’t about the United States. It’s a story from an Australian newspaper about a study by an Australian professor about the Keynesian spending binge in Australia that was enacted back in 2008 and 2009.

I actually gave my assessment of the plan back in 2010, and I even provided my highly sophisticated analysis at no charge.

I actually gave my assessment of the plan back in 2010, and I even provided my highly sophisticated analysis at no charge.

The Treasury-commissioned report, by contrast, presumably wasn’t free. The taxpayers of Australia probably coughed up tens of thousands of dollars for the study.

But this is a rare case where they may benefit, at least if policy makers read the findings and draw the appropriate conclusions.

Here are some of the highlights that caught my eye, starting with a description of what the Australian government actually did.

The GFC fiscal stimulus involved a mix of new public expenditure on school buildings, social housing, home insulation, limited tax breaks for business, and income transfers to select groups. Stimulus packages were announced and implemented in the December 2008, March 2009 quarters and ran into subsequent quarters.

For what it’s worth, there are strong parallels between what happened in the U.S. and Australia.

Both nations had modest-sized Keynesian packages in 2008, followed by larger plans in 2009. The total American “stimulus” was larger because of a larger population and larger economy, of course, and the political situation was also different since it was one government that did the two plans in Australia compared to two governments (Bush in 2008 and Obama in 2009) imposing Keynesianism in the United States.

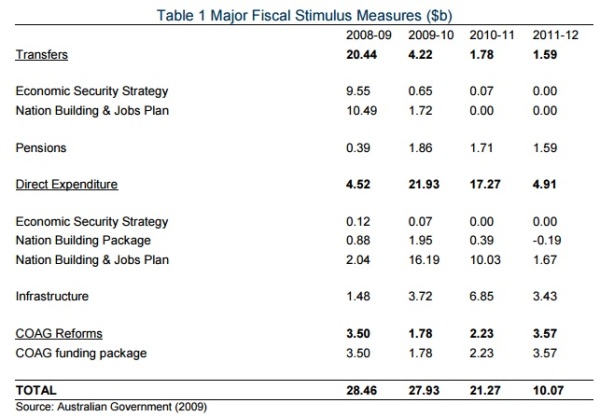

Here’s a table from the report, showing how the money was (mis)spent in Australia.

Now let’s look at the economic impact. We know Keynesianism didn’t work very well in the United States.

And the report suggests it didn’t work any better in Australia.

…fiscal stimulus induced foreign investors to take up newly issued relatively high yielding government bonds whose AAA credit rating further enhanced their appeal. This contributed to exchange rate appreciation and a subsequent competitiveness… Worsened competitiveness in turn reduced the viability of substantial parts of manufacturing, including the motor vehicle sector. …Government spending continued to rise as a proportion of GDP… This put upward pressure on interest rates… this worsened industry competitiveness contributed to major job losses, not gains, in manufacturing and tourism. …In sum, fiscal stimulus was not primarily responsible for saving the Australian economy… Fiscal stimulus later weakened the economy.

Though there was one area where the Keynesian policies had a significant impact.

Australia’s public debt growth post GFC ranks amongst the highest in the G20. Ongoing budget deficits and rising public debt have contributed to economic weakness in numerous ways. …Interest paid by the federal government on its outstanding debt was under $4 billion before the GFC yet could reach $20 billion, or one per cent of GDP, by the end of the decade.

We got a similar result in America. Lots more red ink.

Except our debt started higher and grew by more, so we face a more difficult future (especially since Australia is much less threatened by demographics thanks to a system of private retirement savings).

The study also makes a very good point about the different types of austerity.

…a distinction can be made between “good” and “bad” fiscal consolidation in terms of its macroeconomic impact. Good fiscal repair involves cutting unproductive government spending, including program overlap between different tiers of government. On the contrary, bad fiscal repair involves cutting productive infrastructure spending, or raising taxes that distort incentives to save and invest.

Incidentally, the report noted that the Kiwis implemented a “good” set of policies.

…in New Zealand…marginal income tax rates were reduced, infrastructure was improved and the regulatory burden on business was lowered.

Yet another reason to like New Zealand.

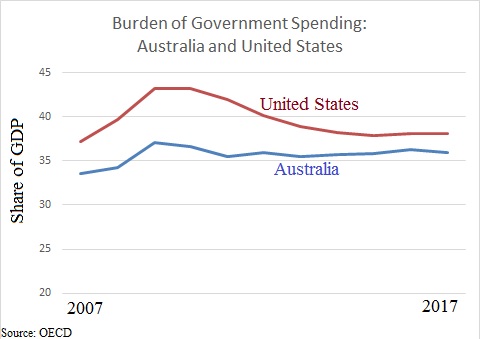

Let’s close by comparing the burden of government spending in the United States and Australia. Using the OECD’s dataset, you see that the Aussies are actually slightly better than the United States.

By the way, it looks like America had a bigger relative spending increase at the end of last decade, but keep in mind that these numbers are relative to economic output. And since Australia only had a minor downturn while the US suffered a somewhat serious recession, that makes the American numbers appear more volatile even if spending is rising at the same nominal rate.

P.S. The U.S. numbers improved significantly between 2009 and 2014 because of a de facto spending freeze. If we did the same thing again today, the budget would be balanced in 2021.