Greece has confirmed that a nation can spend itself into a fiscal crisis.

And the Greek experience also has confirmed that bailouts exacerbate a fiscal crisis by enabling more bad policy, while also rewarding spendthrift politicians  and reckless lenders (as I predicted when Greece’s finances first began to unravel).

and reckless lenders (as I predicted when Greece’s finances first began to unravel).

So now let’s look at a third question: Can a country tax itself to death? Greek politicians are doing their best to see if this is possible, with a seemingly endless parade of tax increases (so many that even the tax-loving folks at the IMF have balked).

At the very least, they’ve pushed the private sector into hospice care.

Let’s peruse a couple of recent stories from Ekathimerini, an English-language Greek news outlet. We’ll start with a rather grim look at a very punitive tax regime that is aggressively grabbing money from taxpayers with arrears.

Tax authorities have confiscated the salaries, pensions and assets of more that 180,000 taxpayers since the start of the year, but expired debts to the state have continued to rise, reaching almost 100 billion euros, as the taxpaying capacity of the Greeks is all but exhausted. In the month of October, authorities made almost 1,000 confiscations a day from people with debts to the state of more than 500 euros. In the first 10 months of the year, the state confiscated some 4 billion euros.

But the Greek government is losing a race. The more it raises taxes, the more people fall behind.

in October alone, the unpaid tax obligations of households and enterprises came to 1.2 billion euros. Unpaid taxes from January to October amounted to 10.44 billion euros,

which brings the total including unpaid debts from previous years to almost 100 billion euros (99.8 billion), or about 55 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. The inability of citizens and businesses to meet their obligations is also confirmed by the course of public revenues, which this year have declined by more than 2.5 billion euros. The same situation is expected to continue into next year, as the new tax burdens and increased social security contributions look set to send debts to the state soaring.

The fact that revenues have declined should be a glaring signal to politicians that they are past the revenue-maximizing point on the Laffer Curve.

But the government probably won’t be satisfied until everyone in the private sector is in debt to the state.

There are now 4.17 million taxpayers who owe the state money. This means that one in every two taxpayers is in arrears to the state, with 1,724,708 taxpayers facing the risk of forced collection measures. Of the 99.8 billion euros of total debt, just 10-15 billion euros is still considered to be collectible.

Here’s another article from Ekathimerini that looks at how Greece is doubling down on suicidal fiscal policy.

Greece is defying the prevalent trend among the world’s industrialized nations for reducing tax rates in order to boost investment and competitiveness… According to the report, in contrast to the majority of OECD member states, Greece has raised taxes and social security contributions as government policy is geared toward reaching fiscal targets, even though this inevitably harms the crisis-hit country’s competitiveness.

It’s hard to think of a tax that Greek politicians haven’t increased.

Greece…is also the only one among them that increased taxes on labor and corporate profits. …eight OECD member states reduced rates in 2017 on an average of 2.7 percent…,

in stark contrast to Greece, which…has the highest corporate tax rates in the OECD compared to 2008. Many countries also offered breaks and reductions on income tax, …also cutting social contributions in 2015-2016. Not so Greece, which in 2016 raised both, thereby increasing the overall burden on low-income earners by 1.5 percent. Greece was also the only country in the OECD to raise value-added tax rates in 2016.

And what was accomplished by all these tax increases? Less tax revenue and recession. That’s a lose-lose scenario by almost any standard.

…in the 2014-2015 period, 25 of the 32 countries for which data is available recorded an increase in tax-to-GDP levels. The report…mentions Greece as an exception to this trend as well, noting that the country was in recession in that two-year period.

Even an establishment outlet like the U.K.-based Financial Times has noticed.

Unemployment is at 23 per cent and 44 per cent of those aged 15-24 are out of work. More than a fifth of Greeks get by without basics such as heating or a telephone connection. …Sweeping new taxes imposed across the economy have already left communities scrabbling to survive. …this year will bring €1bn worth of new taxes on cars, telecoms, television, fuel, cigarettes, coffee and beer… New taxes have eroded disposable incomes still further. Value added tax has increased to 24 per cent on food, disproportionately hurting the poor, for whom living costs represent a far higher proportion of income. Most detested is the Enfia property levy, which brings in €2.65bn a year – roughly €650 from each of Greece’s four million households. …recent direct taxes like the new estate tax have affected households that have seen their income decline greatly during the crisis. The rise of VAT, meanwhile, only adds to the cost of life of poor families.” …this month, new levies will mean the taxes paid by his business will jump 29 per cent.

Interestingly, the article acknowledges that profligate politicians created the mess, while also noting that the Greek people also deserve blame.

…blame is laid on the politicians who spent the 27 years of Greece’s EU membership before the crisis loading the country with debt to fund increased defence expenditure, more public sector jobs and higher pension and other social benefit payments. …“The Greek people should be blamed. We voted for these people,” he concludes.

The problem, of course, is that Greek voters don’t show any interest in now voting for politicians who will clean up the mess. Simply stated, too many people in the country are living off the government.

In other words, even though it’s mathematically possible to fix the problems, the erosion of societal capital suggests that Greece may have reached the point of collapse.

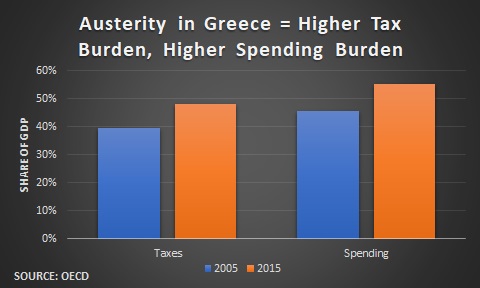

From a fiscal perspective, this chart from OECD data confirms that policy is getting worse rather than better. Measured as a share of economic output, taxes and spending have both become a bigger burden over the past 10 years.

What makes this chart especially depressing is that economic output is lower today than it was in 2005, which means that the problem isn’t so much that annual tax receipts and spending level are climbing, but rather that the private economy is declining.

Let’s close with an additional look at the moribund Greek economy and a discussion of how the bailouts have made a bad situation even worse.

The Wall Street Journal editorialized on the impact of ever-higher taxes and a still-stifling bureaucratic business environment.

…the bailout is not in fact working, if you think the goal should be to restore Athens to sound public finances and to offer Greeks economic hope for the future. The European Commission’s autumn forecast predicts eurozone economic growth of 2.2% this year, the fastest in a decade. But Greece is falling further behind. …Investment has collapsed in the country, to 11% of GDP last year from 26% of GDP in 2007. …The bailouts are creating a dangerous situation in which the government has enough cash to meet its debts but no one else in Greece can thrive.

And here’s the scary part. What happens when there’s another global recession? The already-bad numbers in Greece will get even worse. Not a pleasant thought.

P.S. If you want to know why I’m not optimistic about Greece’s future, how can you expect good policy from a nation that subsidizes pedophiles and requires stool samples to set up online companies? I’d be more hopeful if Greek politicians instead had learned some lessons from Slovakia or Latvia.