Most economic policy debates are predictable. Folks on the left urge higher taxes and bigger government while folks on the right advocate lower taxes and smaller government  (thanks to “public choice” incentives, many supposedly pro-market politicians don’t follow through on those principles once they’re in office, but that’s a separate issue).

(thanks to “public choice” incentives, many supposedly pro-market politicians don’t follow through on those principles once they’re in office, but that’s a separate issue).

The normal dividing line between right and left disappears, however, when looking at whether the welfare state should be replaced by a “universal basic income” that would provide money to every legal resident of a nation.

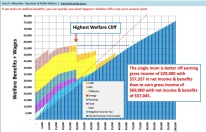

There are some compelling arguments in favor of such an idea. Some leftists like the notion of income security for everybody. Some on the right like the fact that there would be no need for massive bureaucracies to oversee the dozens of income redistribution programs that currently exist.  And since everyone automatically would get a check, regardless of income, lower-income people seeking a better life no longer would face very high implicit tax rates as they replaced handouts with income.

And since everyone automatically would get a check, regardless of income, lower-income people seeking a better life no longer would face very high implicit tax rates as they replaced handouts with income.

But there are plenty of libertarians and small-government conservatives who are skeptical. I’m in this group because of my concern that the net result would be bigger government and I don’t trust that the rest of the welfare state would be abolished. Moreover, I worry that universal handouts would erode the work ethic and exacerbate the dependency problem.

And I have an ally on the other side of the ideological spectrum.

Former Vice President Joe Biden…will push back against “Universal Basic Income,”… UBI is a check to every American adult, but Biden thinks that it’s the job that is important, not just the income. In a blog post…timed to the launch of the Joe Biden Institute at the University of Delaware, Biden will quote his father telling him how a job is “about your dignity. It’s about your self-respect. It’s about your place in your community.”

I often don’t agree with Biden, but he’s right on this issue.

Having a job, earning a paycheck, and being self-sufficient are valuable forms of societal or cultural capital.

By contrast, a nation that trades the work ethic for universal handouts is taking a very risky gamble.

Let’s look at what’s been written on this topic.

In an article for the Week, Damon Linker explores the importance of work and the downside of dependency.

…a UBI would not address (and would actually intensify) the worst consequences of joblessness, which are not economic but rather psychological or spiritual. …a person who falls out of the workforce permanently will be prone to depression and other forms of psychological and spiritual degradation. When we say that an employee “earns a living,” it’s not merely a synonym for “receives a regular lump sum of money.” The element of deserving (“earns”) is crucial. …a job can be and often is a significant (even the primary) source of a person’s sense of self-worth. …A job gives a person purpose, a reason to get up in the morning, to engage with the world and interact with fellow citizens in a common endeavor, however modest. And at the end of the week or the month, there’s the satisfaction of having earned, through one’s own efforts, the income that will enable oneself and one’s family to continue to survive and hopefully even thrive.

Dan Nidess, in a column for the Wall Street Journal, opines about the downsides of universal handouts.

At the heart of a functioning democratic society is a social contract built on the independence and equality of individuals. Casually accepting the mass unemployment of a large part of the country and viewing those people as burdens would undermine this social contract, as millions of Americans become dependent on the government and the taxpaying elite. It would also create a structural division of society that would destroy any pretense of equality. …UBI would also weaken American democracy. How long before the well-educated, technocratic elites come to believe the unemployed underclass should no longer have the right to vote? Will the “useless class” react with gratitude for the handout and admiration for the increasingly divergent culture and values of the “productive class”? If Donald Trump’s election, and the elites’ reactions, are any indication, the opposite is likelier. …In the same Harvard commencement speech in which Mr. Zuckerberg called for a basic income, he also spent significant time talking about the need for purpose. But purpose can’t be manufactured, nor can it be given out alongside a government subsidy. It comes from having deep-seated responsibility—to yourself, your family and society as a whole.

An article in the American Interest echoes this point.

…work, for most people, isn’t just a means of making money—it is a source of dignity and meaning and a central part of the social compact. Simply opting for accelerated creative destruction while deliberately warehousing the part of the population that cannot participate might work as a theoretical exercise, but it does not mesh with the wants and desires and aspirations of human beings. Communities subsisting on UBIs will not be happy or healthy; the spectacle of free public redistribution without any work requirement will breed resentment and distrust.

Writing for National Review, Oren Cass discusses some negative implications of a basic income.

…even if it could work, it should be rejected on principle. A UBI would redefine the relationship between individuals, families, communities, and the state by giving government the role of provider. It would make work optional and render self-reliance moot. An underclass dependent on government handouts would no longer be one of society’s greatest challenges but instead would be recast as one of its proudest achievements. Universal basic income is a logical successor to the worst public policies and social movements of the past 50 years. These have taken hold not just through massive government spending but through fundamental cultural changes that have absolved people of responsibility for themselves and one another, supported destructive conduct while discouraging work, and thereby eroded the foundational institutions of family and community that give shape to society. …Those who work to provide for themselves and their families know they are playing a critical and worthwhile role, which imbues the work with meaning no matter how unfulfilling the particular task may be. As the term “breadwinner” suggests, the abstractions of a market economy do not obscure the way essentials are earned. A UBI would undermine all this: Work by definition would become optional, and consumption would become an entitlement disconnected from production. Stripped of its essential role as the way to earn a living, work would instead be an activity one engaged in by choice, for enjoyment, or to afford nicer things. …Work gives not only meaning but also structure and stability to life. It provides both socialization and a source of social capital. It helps establish for the next generation virtues such as responsibility, perseverance, and industriousness. …there is simply no substitute for stepping onto the first rung. A UBI might provide the same income as such a job, but it can offer none of the experience, skills, or socialization.

Tyler Cowen expresses reservations in his Bloomberg column.

I used to think that it might be a good idea for the federal government to guarantee everyone a universal basic income, to combat income inequality, slow wage growth, advancing automation and fragmented welfare programs. Now I’m more skeptical. …I see merit in tying welfare to work as a symbolic commitment to certain American ideals. It’s as if we are putting up a big sign saying, “America is about coming here to work and get ahead!” Over time, that changes the mix of immigrants the U.S. attracts and shapes the culture for the better. I wonder whether this cultural and symbolic commitment to work might do greater humanitarian good than a transfer policy that is on the surface more generous. …It’s fair to ask whether a universal income guarantee would be affordable, but my doubts run deeper than that. If two able-bodied people live next door to each other, and one works and the other chooses to live off universal basic income checks, albeit at a lower standard of living, I wonder if this disparity can last. One neighbor feels like she is paying for the other, and indeed she is.

In a piece for the City Journal, Aaron Renn also comments on the impact of a basic income on national character. He starts by observing that guaranteed incomes haven’t produced good outcomes for Indian tribes.

…consider the poor results from annual per-capita payments of casino revenues to American Indian tribes (not discussed in the book). Some tribes enjoy a very high “basic income”—sometimes as high as $100,000 per year— in the form of these payments. But as the Economist reports, “as payment grows more Native Americans have stopped working and fallen into a drug and alcohol abuse lifestyle that has carried them back into poverty.”

And he fears the results would be equally bad for the overall population.

Another major problem with the basic-income thesis is that its intrinsic vision of society is morally problematic, even perverse: individuals are entitled to a share of social prosperity but have no obligation to contribute anything to it. In the authors’ vision, it is perfectly acceptable for able-bodied young men to collect a perpetual income while living in mom’s basement or a small apartment and doing nothing but play video games and watch Internet porn.

Jared Dillian also looks at the issue of idleness in a column for Bloomberg.

I do not like the idea of a universal basic income. Its advocates fundamentally misunderstand human nature. What they do not realize about human beings is that for the vast majority of them, a subsistence level of income is enough — and those advocates are blind to the corrosive effects that widespread idleness would have on society. If you give people money for doing nothing, they will probably do nothing. …A huge controlled experiment on basic income has already been run — in Saudi Arabia, where most of the population enjoys the dividends of the country’s oil wealth. Saudi Arabia has found that idleness leads to more political extremism, not less. We have a smaller version of that controlled experiment here in the U.S. — for example, the able-bodied workers who have obtained Social Security Disability Insurance payments and are willing to stay at home for a piddling amount of money. …the overarching principle is that people need work that is worthwhile, for practical and psychological reasons. If we hand out cash to anyone who can fog a mirror, I figure we are about two generations away from revolution.

By the way, it’s not just American Indians and Saudi Arabians that are getting bad results with universal handouts.

Finland has been conducting an experiment and the early results don’t look promising.

The bottom line is that our current welfare system is a dysfunctional mess. It’s bad for taxpayers and recipients.

Replacing it with a basic income probably would make the system simpler, but at a potentially very high cost in terms of cultural capital.

That’s why I view federalism as a much better approach. Get Washington out of the redistribution racket and allow states to compete and innovate as they find ways to help the less fortunate without trapping them in dependency.