Back in 2013, when I was still doing a “question of the week” column, I suggested that Australian was the best option for those contemplating a new home in the event of some sort of Greek-style fiscal collapse in the United States.

I pointed out that America wasn’t in any immediate danger, though I can understand why some people are interested in the question since our long-run outlook is rather grim.

Anyhow, I picked Australia for several reasons, including its geographic position (no unstable welfare states on the border, which is why I didn’t select Switzerland), its private social security system (unfunded liabilities are small compared to the $44 trillion shortfall in America’s government-run system), and its relatively high level of economic freedom.

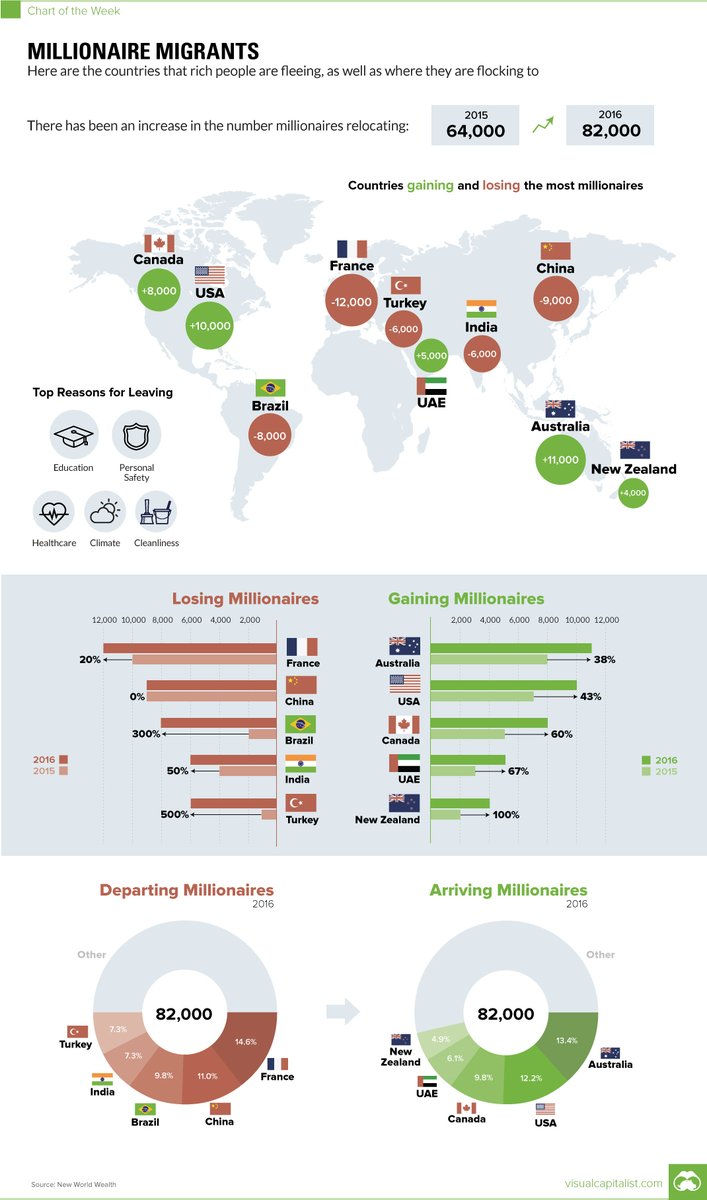

I’m not the only person to notice that Australia is a good place to live. A recent Bloomberg column noted that millionaires are moving Down Under.

They’re all going to the land Down Under. Australia is luring increasing numbers of global millionaires, helping make it one of the fastest growing wealthy nations in the world… Over the past decade, total wealth held in Australia has risen by 85 percent compared to 30 percent in the U.S. and 28 percent in the U.K., aided by the fact that Australia has gone 25 years without a recession. As a result, the average Australian is now significantly wealthier than the average American or Briton. …At the end of 2016 individuals held about $192 trillion of wealth worldwide…, with 13.6 million millionaires holding $69 trillion of this. There were 522,000 multi-millionaires, having net assets of $10 million or more.

The number of millionaires moving to Australia is especially impressive when looking at global data.

Here’s a map showing the nations with the most incoming and outgoing rich people (h/t: Steve Hanke). Maybe it’s because there’s no death tax in Australia, but it’s remarkable that a nation with less than one-tenth the population of the United States manages to attract more millionaires.

But not everybody is cheerful about Australia’s economic position.

I’m currently in Brisbane for a couple of speeches. I spoke earlier today about how market-oriented jurisdictions grow much faster over the long run when compared to nations with statist economic policy.

But I don’t want to focus on my remarks (much of which will be old news to regular readers). Instead, let’s look at the some of the information in a speech by Professor Tony Makin of Griffith University.

Two of his slides caught my attention. Let’s start with a depressing look at how Australia has declined in the global competitiveness rankings put together each year by the World Economic Forum.

This is not a good trend.

That being said, I think Economic Freedom of the World is a more accurate measure and it shows that Australia (whether looking at its absolute score or its relative ranking) has suffered only a small decline.

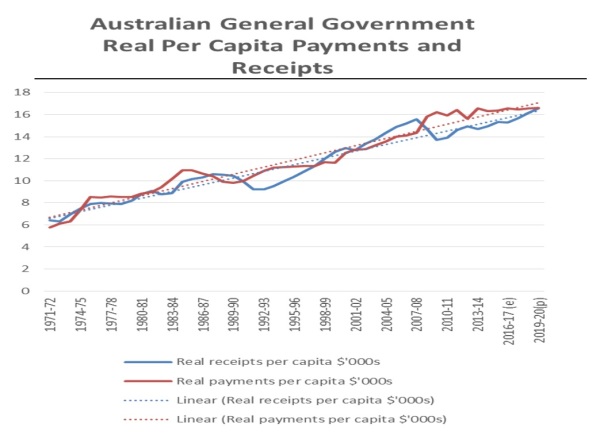

Here’s another chart that is depressing as well. It shows that the per-capita burden of taxes and spending has continuously increased even after adjusting for inflation.

To be fair, the numbers aren’t quite as bad when looking at taxes and spending as a share of gross domestic product.

Nonetheless, the trend isn’t favorable, which is a point I made back in 2014.

None of this changes my view that Australia is still a good choice for emigrating Americans. But it does leave me worried about whether it will still be the top choice in 10 years or 20 years.

For what it’s worth, the main recommendation in my speech was for Australia to adopt a spending cap, similar to the ones that exist in Hong Kong and Switzerland. I also should have suggested sweeping decentralization since the government actually is open to that idea.

P.S. One of the most disappointing things about Australia is that the country’s foreign aid bureaucrats are trying to bribe/coerce Vanuatu’s government into adopting an income tax.

P.P.S. Professor Makin was the author of the report I recently cited about the failure of Australia’s Keynesian spending binge.

———

Image credit: Chris Samuel | CC BY 2.0.