I confess that I’m never sure how best to persuade and educate people about the value of limited government.

- Is it best to make a moral and philosophical case against state coercion?

- Or is it best to make a practical case that a free society produces greater prosperity?

Regular readers presumably will put me in the second camp since most of my columns involve data and evidence on the superior outcomes associated with markets compared to statism.

That being said, I actually don’t think we will prevail until and unless we can convince people that it is ethically wrong to use government power to dictate and control the lives of other people.

So I’m always trying to figure out what motivates people and how they decide what policies to support.

With this in mind, I was very interested to see that nine scholars from five continents (North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Australia), representing six countries (Canada, United States, Argentina, Netherlands, Israel, and Australia) and four disciplines (psychology, criminology, economics, and anthropology), produced a major study on what motivates support for redistribution.

Why do people support economic redistribution? …By economic redistribution, we mean the modification of a distribution of resources across a population as the result of a political process. …it is worthwhile to understand how distributive policies are mapped into and refracted through our evolved psychological mechanisms.

The study explains how human evolution may impact our attitudes, a topic that I addressed back in 2010.

The human mind has been organized by natural selection to respond to evolutionarily recurrent challenges and opportunities pertaining to the social distribution of resources, as well as other social interactions.…For example, it was hypothesized that modern welfare activates the evolved forager risk-pooling psychology — a psychology that causes humans to be more motivated to share when individual productivity is subject to chance-driven interruptions, and less motivated to share when they think they are being exploited by low-effort free riders. Ancestrally, sharing resources that came in unsynchronized, high-variance, large packages (e.g., large game) allowed individuals to buffer each other’s shortfalls at low additional cost.

Here’s how the authors structured their research.

…we propose that the mind perceives modern redistribution as an ancestral game or scene featuring three notional players: the needy other, the better-off other, and the actor herself. …we use the existence of individual differences in compassion, self-interest, and envy as a research tool for investigating the joint contribution of these motivational systems to forming attitudes about redistribution.

And here’s how they conducted their research.

We conducted 13 studies with 6,024 participants in four countries to test the hypothesis that compassion, envy, and self-interest jointly predict support for redistribution. Participants completed instruments measuring their (i) support for redistribution; (ii) dispositional compassion; (iii) dispositional envy; (iv) expected personal gain or loss from redistribution (our measure of self-interest); (v) political party identification; (vi) aid given personally to the poor; (vii) wealthy-harming preferences; (viii) endorsement of pro-cedural fairness; (ix) endorsement of distributional fairness; (x) age; (xi) gender; and (xii) socioeconomic status (SES).

Now let’s look at some of the findings, starting with the fact that personal compassion is not associated with support for coerced redistribution. Indeed, advocates of government redistribution tend to be less generous (a point that I’ve previously noted).

Consider personally aiding the poor—as distinct from supporting state-enacted redistribution. Participants in the United States, India, and the United Kingdom (studies 1a–c) were asked whether they had given money, food, or other material resources of their own to the poor during the last 12 mo; 74–90% of the participants had. …dispositional compassion was the only reliable predictor of giving aid to the poor. A unit increase in dispositional compassion is associated with 161%, 361%, and 96% increased odds of having given aid to the poor in the United States, India, and the United Kingdom. …Interestingly, support for government redistribution was not a unique predictor of personally aiding the poor in the regressions… Support for government redistribution is not aiding the needy writ large—in the United States, data from the General Social Survey indicate that support for redistribution is associated with lower charitable contributions to religious and nonreligious causes (61). Unlike supporting redistribution, aiding the needy is predicted by compassion alone.

But here’s the most shocking part of the results.

The people motivated by envy are often interested in hurting those above them than they are in helping those below them.

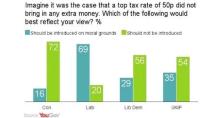

…consider envy. Participants in the United States, India, and the United Kingdom (studies 1a–c) were given two hypothetical scenarios and asked to indicate their preferred one. In one scenario, the wealthy pay an additional 10% in taxes, and the poor receive an additional sum of money. In the other scenario, the wealthy pay an additional 50% in taxes (i.e., a tax increment five times greater than in the first scenario), and the poor receive (only) one-half the additional amount that they receive in the first scenario. That is, higher taxes paid by the wealthy yielded relatively less money for the poor, and vice versa… Fourteen percent to 18% of the American, Indian, and British participants indicated a preference for the scenario featuring a higher tax rate for the wealthy even though it produced less money to help the poor (SI Appendix, Table S3). We regressed this wealthy-harming preference simultaneously on support for redistribution… Dispositional envy was the only reliable predictor. A unit increase in envy is associated with 23%, 47%, and 43% greater odds of preferring the wealthy-harming scenario in the United States, India, and the United Kingdom.

This is astounding, in a very bad way.

It means that there really are people who are willing to  deprive poor people so long as they can hurt rich people.

deprive poor people so long as they can hurt rich people.

Even though I have shared polling data echoing these findings, I still have a hard time accepting that some people think like that.

But the data in this study seem to confirm Margaret Thatcher’s observation about what really motivates the left.

The authors have a more neutral way of saying this. They simply point out that compassion and envy can lead to very different results.

Compassion and envy motivate the attainment of different ends. Compassion, but not envy, predicts personally helping the poor. Envy, but not compassion, predicts a desire to tax the wealthy even when that costs the poor.

Since we’re on the topic or morality, markets, and statism, my colleague Ryan Bourne wrote an interesting column for CapX looking at research on what type of system brings out the best in people.

It turns out that markets promote cooperation and trust.

…experimental work of Herbert Gintis, who has analysed the behaviours of 15 tribal societies from around the world, including “hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, nomadic herders, and small-scale sedentary farmers — in Africa, Latin America, and Asia.” Playing a host of economic games, Gintis found that societies exposed to voluntary exchange through markets were more highly motivated by non-financial fairness considerations than those which were not. “The notion that the market economy makes people greedy, selfish, and amoral is simply fallacious,” Gintis concluded. …Gintis again summarises, “movements for religious and lifestyle tolerance, gender equality, and democracy have flourished and triumphed in societies governed by market exchange, and nowhere else.”

Whereas greater government control and intervention produce a zero-sum mentality and cheating.

…we might expect greed, cheating and intolerance to be more prevalent in societies where individuals can only fulfil selfish desires by taking from, overpowering or using dominant political or hierarchical positions to rule over and extort from others. Markets actually encourage collaboration and exchange between parties that might otherwise not interact. This interdependency discourages violence and builds trust and tolerance. …In a 2014 paper, economists tested Berlin residents’ willingness to cheat in a simple game involving rolling die, whereby self-reported scores could lead to small monetary pay-offs. Participants presented passports and ID cards to the researchers, which allowed them to assess their backgrounds. The results were clear: participants from an East German family background were far more likely to cheat than those from the West. What is more, the “longer individuals were exposed to socialism, the more likely they were to cheat.”

All of which brings me back to where I started.

How do you persuade people to favor liberty if they are somehow wired to have a zero-sum view of the world and they think that goal of public policy is to tear down the rich, even if that hurts the poor?

Though the internal inconsistency of the previous sentence maybe points to the problem. If the poor and the rich are both hurt by a policy (or if both benefit from a policy), then the world clearly isn’t zero-sum. And we now from voluminous evidence, of course, that the world isn’t that way.

But how to convince people, other than making the same arguments over and over again?

P.S. Jonah Goldberg and Dennis Prager both have videos with some insight on this issue.