Since the House has passed a tax cut and the Senate has passed a tax cut, it’s quite likely that there will be a consensus deal that will be signed into law.

Which makes me happy since any agreement presumably will include a lower corporate tax rate and the elimination of the deduction for state and local income taxes.

But some folks don’t think this is good news.

Writing for U.S. News & World Report, Pat Garofalo argues that taxes should be going up.

The entire bill is premised off the belief that taxes are too high and need to go down, when the opposite is actually true. …the U.S. is, by developed country standards, a very low-tax country. It raises about a quarter of its gross domestic product in revenue at all levels of government, compared to about a third in the rest of the developed world, and well more than 40 percent in some countries. For the last several decades, the U.S. at the federal level alone has raised roughly 18 percent of GDP in taxes, while spending around 20 percent. Sorry, but that just doesn’t cut it. …other countries prove there’s plenty of room to raise more revenue without kneecapping economic growth. …America’s concentration of wealth is such that there’s plenty of room to raise taxes on the rich with nary an economic blip… it is possible, as Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., does all the time, to make a case that, yes, taxes on the middle class will go up, but that the benefits will be more than worth it.

I won’t bother responding to all his inaccurate assertions, but I will give Mr. Garofalo credit for honesty. Unlike a lot of folks on the left, he openly acknowledges that the middle class will have to be pillaged to finance a European-style welfare state. I’ll add him to my list of honest leftists.

But honesty is not the same as accuracy.

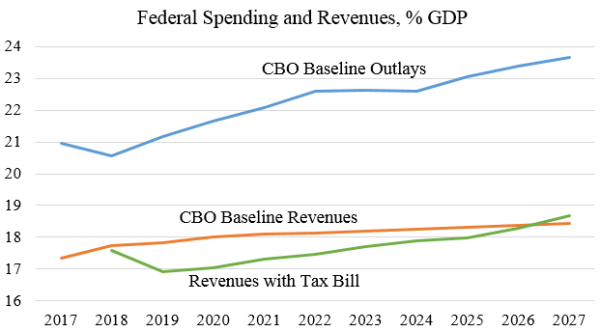

Chris Edwards put together a very helpful chart showing federal taxes and revenues as a share of economic output. As you can see, America’s real fiscal problem is government spending. The tax cut being considered on Capitol Hill only causes a small – and completely temporary – drop in revenues.

This is such good information that it deserves a closer look.

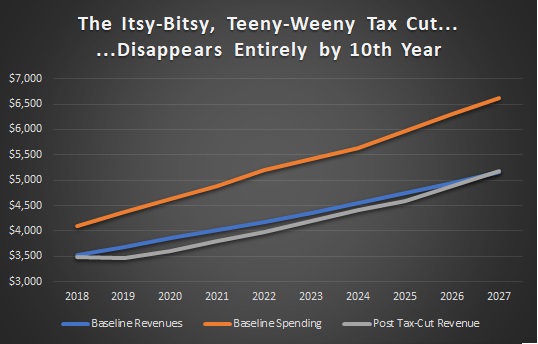

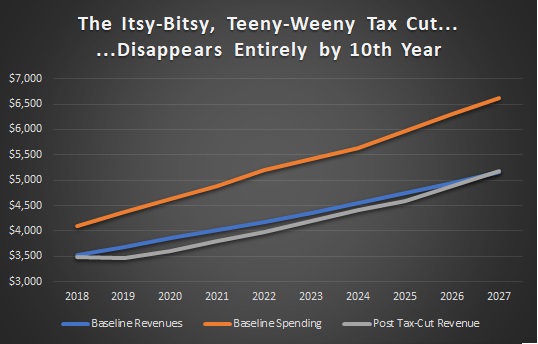

I decided to look at the raw year-to-year numbers. I got the latest 10-year budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office, as well as the 10-year projections for the Senate tax bill from the Joint Committee on Taxation (the House bill’s numbers are very similar, so these figures presumably are a very accurate proxy of any final package).

Let’s start with a look at the annual baseline revenues (blue) and annual baseline spending (orange), along with the annual post-tax cut revenues (grey). As you can see, there’s very little difference in the two revenue lines. There’s some short-run aggregate tax relief, but that quickly begins to shrink. And by the 10th year, the federal government actually will be collecting more revenue!

Some people nonetheless will oppose even a tiny and temporary tax cut. They will claim they want to balance the budget (though oftentimes these are the same people who supported the faux stimulus and wanted the new Obamacare entitlement, so judge for yourself whether they are sincere).

Even in the unlikely event that they are sincere, their complaints don’t make sense since revenues will be higher after 10 years. And that’s not even properly considering the impact of additional economic growth, which would cause tax receipts to grow even faster.

But let’s set that aside and consider what would be necessary to balance the budget over the 10-year budget window. Earlier this year, I calculated that it would be possible to balance the budget and enact a $3 trillion tax cut so long as politicians would simply restrain federal spending so that it grew by 1.96 percent per year.

Based on the most recent numbers (and starting the spending restraint in 2019 rather than 2018), the budget can be balanced if federal spending grows by 2.67 percent annually. Since that’s much faster than what would be necessary to keep pace with inflation (projected to average about 2 percent per year), this wouldn’t require any “harsh” austerity.

By the way, if you want an example of successful multi-year spending restraint, we had a five-year de facto spending freeze from 2009-2014 (yes, those fights over debt limits, sequestration, and government shutdowns produced a big payoff).

Heck, when Clinton was in the White House, overall government spending grew by 3.2 percent annually between 1993 and 1999.

Surely Republicans can beat Bill Clinton’s record, right?

I’ll close by observing that we shouldn’t fixate on balancing the budget in any particular year. It’s much more important to shrink the burden of government spending. And that happens when the private sector grows faster than the federal budget.

To be sure, it’s also a good idea to shrink red ink, at least relative to our ability to finance debt. That happens whenever the private economy grows faster than federal borrowing.

The good news is that spending restraint is the one policy that achieves both goals.