It’s time to channel the wisdom of Frederic Bastiat.

There are many well-meaning people who understandably want to help workers by protecting them from bad outcomes such as pay reductions, layoffs, and discrimination.

My normal response is to remind them that the best thing for workers is a vibrant and growing economy. That’s the kind of environment that produces tight labor markets and more investment, both of which then lead to higher pay.

Even statists sort of understand that this is true, but it’s sometimes difficult to get them to grasp the implications. They oftentimes are drawn to specific forms of government intervention, even if you explain that there are adverse unintended consequences.

- Higher minimum wages push marginal workers into joblessness.

- Pro-feminist policies make women less attractive to employers.

- Labor protection laws discourage companies from hiring workers.

Let’s explore this issue further.

In a column for the New York Times, Megan McGrath writes about a big new mining project in a remote part of Australia that “has the potential to create 10,000 jobs.” While that’s obviously good news, she worries that the company “will repeat the mistakes made by companies during the last mining boom by using workplace practices that hurt workers and their families.”

And what are these mistaken “workplace practices”? Apparently, she thinks it is terrible that workers don’t want to move to the outback and instead prefer to continue living in cities and suburbs. So she thinks it is bad that they fly in for multi-week shifts, stay in temporary housing, and then fly back (at company expense) to their homes.

Employees…fly to remote mines from major cities to work weeks at a time, and fly home for several days off before starting the cycle again. These so-called fly-in, fly-out jobs, which offer hefty pay, are widely known here as “fifo.” At the peak of the boom in 2012, …more than 100,000 of these held fifo positions.

Though it seems these workers are making very rational decisions on how to maximize the net benefits of these positions.

…fifo workers in the last boom were young, undereducated men lured by salaries that far surpassed what they could earn for similar work outside the industry — up to $100,000 a year to shift earth and drive trucks. The average full-time mining employee in 2016 earned $1,000 more per week than other Australians.

So what’s the downside? Why are workers supposedly being exploited by these lucrative jobs?

According to McGrath, the mining camps don’t have a lot of amenities.

…fifo life comes at a steep price. The management in many mines controls the transient workers’ schedules — setting times for meals, showers and sleep. The workers often can’t visit nearby towns and recreational facilities such as gyms and swimming pools because of a lack of transportation. Many employees have to share beds. They work 12-hour shifts, seven days a week, up to three weeks at a time.

That doesn’t sound great, but this also explains why the mining companies have to pay a boatload of money to attract workers. This is a well-established pattern that is familiar to labor economists. If working conditions are unpalatable, then employers have to compensate with more remuneration.

But Ms. McGrath doesn’t think workers should get extra cash. She would rather the mining company compensate workers indirectly.

A lot can be done to improve life in the camps. Shorter swings would help workers maintain bonds with their families. More stable living situations, with less sharing of living spaces, would increase a sense of value and belonging. Workers should be encouraged to visit nearby towns to reduce their isolation. The Adani megamine could be in operation for 60 years, experts say. Roads for the mine and the region should be improved so employees can move with their families to existing townships and drive to work.

Of course, she doesn’t admit that she wants workers to get less cash compensation, but that would be the real-world impact of her proposed policies.

She says that the mining companies should “put people ahead of profits.” But that’s a vacuous statement. Projects like this new mine only exist because investors expect to earn a return.  Otherwise, they wouldn’t take the enormous risk of sinking so much capital into such endeavors.

Otherwise, they wouldn’t take the enormous risk of sinking so much capital into such endeavors.

All this new investment is good news for unemployed or under-employed Australians since they’ll now have an opportunity to compete for jobs that pay very well, particularly for workers without a lot of education.

By the way, if workers really valued all the things that are on Ms. McGrath’s list, the company would offer those fringe benefits instead of higher wages. But that’s obviously not the case. The market has spoken.

By the way, I can’t resist pointing out that she also does not understand tax policy. In a sensible system, companies calculate their taxable profit by adding up their total revenue and then subtracting all their costs. What’s left is profit, a slice of which is then grabbed by the government.

But that’s not enough for Ms. McGrath. She apparently believes that mining companies shouldn’t be allowed to subtract many of the costs associated with so-called fifo workers when calculating their annual profit. I’m not joking.

Mining companies are encouraged through tax incentives to use the transient workers. Some costs associated with a fifo worker — meals, transportation and airline tickets — can be claimed as production expenses, helping to lower a company’s tax bill.

I hope the Australian government isn’t dumb enough to buy this argument. Allowing a firm to subtract costs when calculating profit is simply common sense. And if doesn’t matter if those costs reflect fifo costs, investment expenditures, luxury travel, or band costumes.

For what it’s worth, if the government does get pressured into forcing companies to pay tax on these various business expenses, one very safe prediction is that the net effect will be to lower the wages offered to workers. Or, if the mandates, taxes, and regulations reach a certain level, the business will simply close down or new projects will be abandoned.

And those options obviously are not good news for workers.

Let’s now shift from the specific example of fifo workers to the broader issue of labor regulation. What happens if governments listen to people like Ms. McGrath and impose all sorts of rules that prevent flexible labor markets? According to recent scholarly research from three European economists, the consequence is more unemployment.

They start by pointing out that European nations with mandates and red tape have a lot more unemployment (particularly when the economy is weak) than countries with lightly regulated labor markets.

The Great Recession has brought a substantial increase in unemployment in Europe. Overall, unemployment rate in the euro area has grown from 8 percent in 2008 to 12 percent in 2014. The change in unemployment has been very heterogenous. In northern Europe, unemployment did not grow substantially or even fell: in Germany, for example, unemployment rate has actually declined from 7 to 5 percent. At the same time, in Greece unemployment has grown from 8 to 26 percent, in Spain — from 8 to 24 percent, and in Italy — from 6 to 13 percent. Why has unemployment dynamics been so different in European countries? The most common explanation is the difference in labor market institutions that prevents wages from adjusting downward. If wages cannot decline, negative aggregate demand shocks (such as the Great Recession) result in growth of unemployment.

The three economists wanted some way to test the impact of regulation, so they looked at the labor market for immigrants in Italy since some of them work in the formal (regulated) economy and some of them work in the shadow (unregulated) economy.

While this argument is straightforward, it is not easy to test empirically. Cross-country studies of labor markets are subject to comparability concerns. The same problems arise in comparing labor markets in different industries within the same country. In order to construct a convincing counterfactual for a regulated labor market, one needs to study a non-regulated labor market in the same sector within the same country. This is precisely what we do in this paper through comparing formal and informal markets in Italy over the course of 2004-12. We use a unique dataset, a large annual survey of immigrants working in Lombardy carried out by ISMU Foundation since 2004. …Our data cover 4000 full-time workers every year; one fifth of them works in the informal sector. The dataset is therefore sufficiently large to allow us comparing the evolution of wages in the formal and in the informal sector controlling for occupation, skills and other individual characteristics.

And what did they find?

In the absence of regulation, labor markets can adjust. The bad news for workers is that they get less pay. But the good news is that they’re more likely to still have jobs.

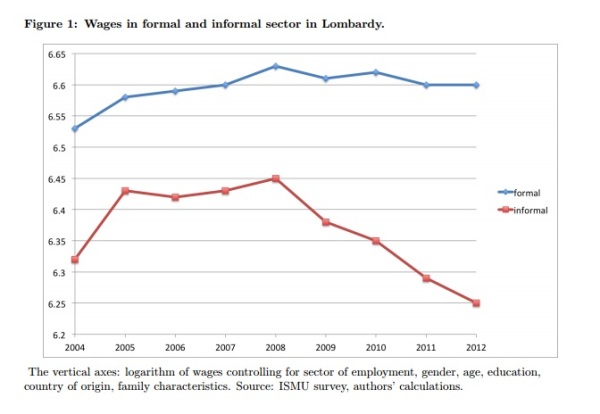

Our main result is presented in Figure 1. We do find that the wage differential between formal and informal sector has increased after 2008. Moreover, while the wages in the informal sector decreased by about 20 percent in 2008-12, the wages in the formal sector virtually did not fall at all. This is consistent with the view that there is substantial downward stickiness of wages in the regulated labor markets. …we find that both before and during the crisis, undocumented immigrants (those without a regular residence permit) are 9 percentage points more likely than documented immigrants to be in the labor force

Here’s the relevant chart from the study.

And here are some concluding thoughts from the study.

…despite the substantial growth of unemployment in 2008-12, the wages in the formal labor market have not adjusted. In the meanwhile, the wages in the unregulated informal labor market have declined substantially. The wage differential between formal and informal market that has been constant in 2004-08 has grown rapidly in 2008-12 from 18 to 35 percentage points. …These results are consistent with the view that regulation is responsible for lack of wage adjustment and increase in unemployment during the recessions.

For what it’s worth (and this is an important point), this helps explain why the Great Depression was so awful. Hoover and Roosevelt engaged in all sorts of interventions designed to “help” workers. But the net effect of these policies was to prevent markets from adjusting. So what presumably would have been a typical recession turned into a decade-long depression.

So what’s the moral of the story? Good intentions aren’t good if they lead to bad results. Which brings me back to my original point about helping workers by minimizing government intervention.

———

Image credit: Alfred Palmer | Public Domain.