Over the past few weeks, I’ve written several columns about the 100th anniversary of communism. I’ve looked at that evil ideology’s death toll, and I’ve written about the knaves and fools who defended and promoted communism in the west (included, sad to say, some economists). And I’ve even shared some anti-communist humor to offset the dour material in the other columns.

Let’s continue that series today by looking at the very practical question of what happens when a nation breaks free from communist enslavement?

Professor James Gwartney and Hugo Montesinos from Florida State University analyzed the economic performance of former Soviet Bloc nations (they refer to them as formerly centrally planned – or FCP – countries) over the past 20 years.

The good news is that these countries have been growing, especially if they get decent scores from Economic Freedom of the World.

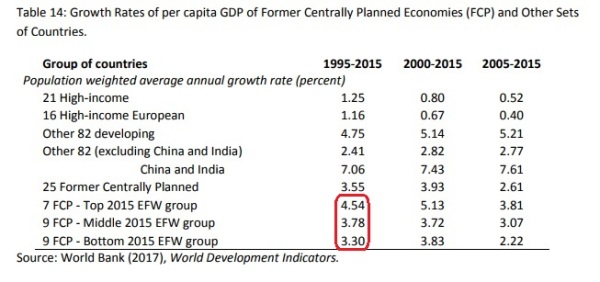

The economic record of the FCP countries during 1995-2015 was impressive. This was particularly true for the seven FCP countries that moved the most toward economic liberalization. The average growth of real per capita GDP of these seven countries exceeded 5 percent during 1995-2015. Real per capita GDP more than doubled in six of the seven countries during the two decades. …While the real GDP growth of the middle group was slower, it was still impressive. The population weighted annual real growth of per capita GDP of the middle group was 3.78 percent.

And to elaborate on the good news, growth rates in FCP nations has been faster than growth rates in rich countries.

But that’s to be expected. Convergence theory tells us that poorer places should grow faster than richer places (at least in the absence of unusual circumstances).

But government policy can be a wild card. As you can see from Table 14 of the report, Gwartney and Montesinos parsed the data and found that the FCP nations that adopted the most pro-market reforms have enjoyed the fastest growth rates, while growth rates were less impressive in the FCP countries with lesser amounts of economic liberalization (relative growth rates highlighted in red below).

The goal, of course, is for FCP nations to catch up with rich nations.

And there has been a decent amount of convergence.

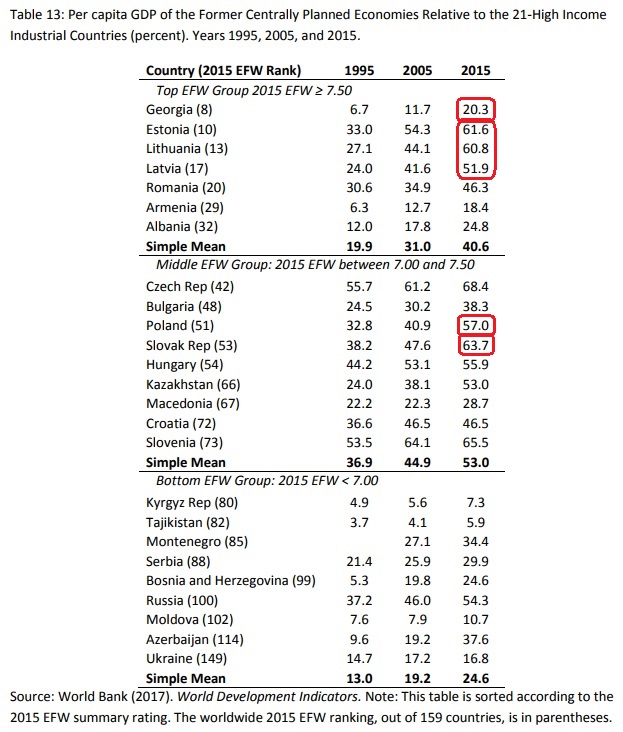

…the relative income increases are impressive. The ratio of the mean per capita GDP of the most economically free group compared to the high-income economies more than doubled, soaring from 19.9 percent in 1995 to 40.6 percent in 2015. The parallel ratio for the middle group increased by approximately 50 percent from 36.9 percent in 1995 to 53.0 percent in 2015. Finally, the ratio for the bottom group increased from 13.0 percent in 1995 to 24.6 percent in 2015, an increase of 90 percent. The largest increases in relative income were registered by Georgia, Lithuania, Latvia, Armenia, Albania, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ratio for each of these countries more than doubled between 1995 and 2015. Note that five of these eight countries are in the group with the highest 2015 EFW ratings.

There’s country-specific data in Table 13 of the report.

And you can see, once again, that the nations with the most economic freedom and enjoying the fastest convergence rates. From the top group, I’ve highlighted both Georgia and the Baltic countries for their impressive results. And I also highlighted Poland and Slovakia from the second group because both countries have converged at a rapid pace thanks to some good policies.

Looking at the bottom group, it’s sad to see Ukraine doing so poorly, but that’s a predictable result given the near-total absence of economic freedom in that unfortunate country.

The obvious moral of the story is that nations will grow faster and generate more prosperity if they follow the recipe of free markets and limited government.

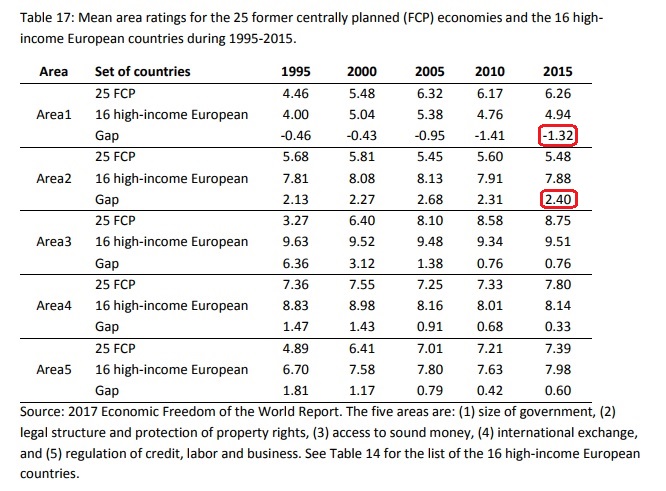

So let’s take a look at that recipe by examining how FCP nations have performed when looking at the various ingredients. More specifically, Economic Freedom of the World looks at five major policy areas: fiscal, trade, money, regulation, and legal.

And it’s that final category (which measures factors such as property rights, the rule of law, and government corruption) where these countries have not done a good job.

…the FCP countries…have a major shortcoming: their legal systems are weak and little progress has been made in this area. Given their historic background, this is not surprising. Under socialism, legal systems are designed to serve the interests of the government. Judges, lawyers, and other judicial officials are trained and rewarded for serving governmental interests. Protection of the rights of individuals and private businesses and organizations is unimportant under socialism.

Here’s some fascinating data from Table 17, which shows how scores for the five major categories have changed over time in both FCP nations and countries from Western Europe. You’ll see that FCP countries have liberalized policy and closed the gap in Area 3 (money), Area 4 (trade), and Area 5 (regulation). And you’ll also see how the FCP nations do a better job in Area 1 (fiscal), which I’ve highlighted in red. But the most startling – and depressing – result in the absence of progress in Area 2 (legal), which is also highlighted in red.

These results, for all intents and purposes, are a much more detailed version of an article I wrote for the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformers in Europe earlier this year.

Unfortunately, even though we have the same diagnosis, we don’t really have an easy solution. In this final excerpt, the authors explain that it’s not that easy to change the culture of a nation’s political class.

It is a major challenge to convert a socialist legal system into one that enforces contracts in an unbiased manner, protects property rights, permits markets to direct economic activity, and operates under rule of law principles. …Economists have provided policy-makers with step by step directions about how to achieve monetary and price stability, liberalized trade regimes, and adopt tax structures more consistent with growth and prosperity. …But, a recipe for developing a sound legal system is largely absent. We know what a sound legal system looks like, but we have failed to explain how it can be achieved.

I don’t even thank socialism deserves the full blame (though it deserves the blame for many bad things). There are many nations in many regions of the world that get very bad scores because of inadequate rule of law and weak property rights. But I fully agree that it’s not easy to fix.

But I’ll close with a very upbeat observation that all of the FCP nations are better off because the Soviet Union collapsed and communism is fading from the world. Liberal socialism may not be good for an economy, but it’s paradise compared to Marxist socialism.