Imagine if you had the chance to play basketball against a superstar from the NBA like Stephen Curry.

No matter how hard you practiced beforehand, you surely would lose. For most people, that would be fine. We would console ourselves with the knowledge that we tried our best and relish the fact that we even got the chance to be on the same court as a professional player.

But some people would want to cheat to make things “equal” and “fair.” So they would say that the NBA player should have to play blindfolded, or play while wearing high-heeled shoes.

And perhaps they could impose enough restrictions on the NBA player that they could prevail in a contest.

But most of us wouldn’t feel good about “winning” that kind of battle. We would be ashamed that our “victory” only occurred because we curtailed the talents of our opponent.

Now let’s think about this unseemly tactic in the context of corporate taxation and international competitiveness.

The United States has the highest corporate tax rate in the industrialized world, combined with having the most onerous “worldwide” tax system among all developed nations.

The United States has the highest corporate tax rate in the industrialized world, combined with having the most onerous “worldwide” tax system among all developed nations.

This greatly undermines the ability of U.S.-domiciled companies to compete in world markets and it’s the main reason why so many companies feel the need to engage in inversions.

So how does the Obama Administration want to address these problems? What’s their plan to reform the system to that American-based firms can better compete with companies from other countries?

Unfortunately, there’s no desire to make the tax code more competitive. Instead, the Obama Administration wants to change the laws to make it less attractive to do business in other nations. Sort of the tax version of hobbling the NBA basketball player in the above example.

Here are some of the details from the Treasury Department’s legislative wish list.

The Administration proposes to supplement the existing subpart F regime with a per-country minimum tax on the foreign earnings of entities taxed as domestic C corporations (U.S. corporations) and their CFCs. …Under the proposal, the foreign earnings of a CFC or branch or from the performance of services would be subject to current U.S. taxation at a rate (not below zero) of 19 percent less 85 percent of the per-country foreign effective tax rate (the residual minimum tax rate). …The minimum tax would be imposed on current foreign earnings regardless of whether they are repatriated to the United States.

There’s a lot of jargon in those passages, and even more if you click on the underlying link.

So let’s augment by excerpting some of the remarks, at a recent Brookings Institution event, by the Treasury Department’s Deputy Assistant Secretary for International Tax Affairs. Robert Stack was pushing the President’s agenda, which would undermine American companies by making it difficult for them to benefit from good tax policy in other jurisdictions.

He actually argued, for instance, that business tax reform should be “more than a cry to join the race to the bottom.”

In other words, he doesn’t (or, to be more accurate, his boss doesn’t) want to fix what’s wrong with the American tax code.

So he doesn’t seem to care that other nations are achieving good results with lower corporate tax rates.

I do not buy into the notion that the U.S. must willy-nilly do what everyone else is doing.

And he also criticizes the policy of “deferral,” which is a provision of the tax code that enables American-based companies to delay the second layer of tax that the IRS imposes on income that is earned (and already subject to tax) in other jurisdictions.

I don’t think it’s open to debate that the ability of US multinationals to defer income has been a dramatic contributor to global tax instability.

He doesn’t really explain why it is destabilizing for companies to protect themselves against a second layer of tax that shouldn’t exist.

But he does acknowledge that there are big supply-side responses to high tax rates.

…large disparity in income tax rates…will inevitably drive behavior.

Too bad he doesn’t draw the obvious lesson about the benefits of low tax rates.

Anyhow, here’s what he says about the President’s tax scheme.

The President’s global minimum tax proposal…permits tax-free repatriation of amounts earned in countries taxed at rates above the global minimum rate. …the global minimum tax plan also takes the benefit out of shifting income into low and no-tax jurisdictions by requiring that the multinational pay to the US the difference between the tax haven rate and the U.S. rate.

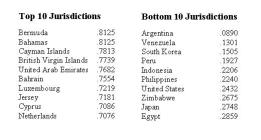

American companies would be taxed by the IRS for doing business in low-tax jurisdictions such as Ireland, Hong Kong, Switzerland, and Bermuda. But if they do business in high-tax nations such as France, there’s no extra layer of tax.

The bottom line is that the U.S. tax code would be used to encourage bad policy in other countries.

Though Mr. Stack sees that as a feature rather than a bug, based on the preposterous assertion that other counties will grow faster if the burden of government spending is increased.

…the global minimum tax concept has an added benefit as well…protecting developing and low-income countries…so they can mobilize the necessary resources to grow their economies.

And he seems to think that support from the IMF is a good thing rather than (given that bureaucracy’s statist orientation) a sign of bad policy.

At a recent IMF symposium, the minimum tax was identified as something that could be of great help.

The bottom line is that the White House and the Treasury Department are fixated at hobbling competitors by encouraging higher tax rates around the world and making sure that American-based companies are penalized with an extra layer of tax if they do business in low-tax jurisdictions

For what it’s worth, the right approach, both ethically and economically, is for American policy makers to focus on fixing what’s wrong with the American tax system.