I’m not the biggest fan of Paul Krugman in his role as a doctrinaire advocate of leftist policy (he used to be within the mainstream and occasionally point out the risks of government intervention in his former role as an academic economist).

It’s not just that he believes in big government. He also has an unfortunate habit of misinterpreting (the charitable explanation) data when advocating higher taxes and more spending.

- In 2015, he cherry-picked job numbers to make it seem as if Obama’s policies were producing good employment data.

- Earlier that year, Krugman asserted that America was outperforming Europe because our fiscal policy was more Keynesian,

yet the data showedthat the United States had bigger spending reductions and less red ink.

yet the data showedthat the United States had bigger spending reductions and less red ink. - In 2014, he asserted that a supposed “California comeback” in jobs somehow proved my analysis of a tax hike was wrong, yet only four states at the time had a higher unemployment rate than California.

- And here’s my favorite: In 2012, Krugman engaged in the policy version of time travel by blaming Estonia’s 2008 recession on spending cuts that took place in 2009.

As you can see, he’s not exactly a paragon of sound thinking and careful analysis.

But there must be a blue moon in the forecast because the New York Timescolumnist has an accurate criticism of Donald Trump’s tax plan.

Before sharing Krugman’s critique, here’s the position of the Trump campaign, which asserts that the World Trade Organization has rigged the rules against America by allowing nations to give rebates to exporters so that there is no value-added tax (VAT) on good and services sold to consumers in other nations.

…there is a more subtle tax problem pulling US corporations offshore. It relates to the unequal treatment of the US income tax system by the World Trade Organization (WTO). …While the US operates primarily on an income tax system, all of America’s major trading partners depend heavily on a “value-added tax” or VAT system. Under current rules, the WTO allows America’s trading partners to effectively create backdoor tariffs to block American exports and backdoor subsidies to penetrate US markets. Here’s how this exploitation works: VAT rates are typically between 15% and 25%. …Under WTO rules, any foreign company that manufactures domestically and exports goods to America (or elsewhere) receives a rebate on the VAT it has paid. This turns the VAT into an implicit export subsidy. At the same time, the VAT is imposed on all goods that are imported and consumed domestically so that a product exported by the US to a VAT country is subject to the VAT. This turns the VAT into an implicit tariff on US exporters over and above the US corporate income taxes they must pay. Thus, under the WTO system, American corporations suffer a “triple whammy”: foreign exports into the US market get VAT relief, US exports into foreign markets must pay the VAT, and US exporters get no relief on any US income taxes paid. The practical effect of the WTO’s unequal treatment of America’s income tax system is to give our major trading partners a 15% to 25% unfair tax advantage in international transactions.

In the wonky jargon of public finance, VATs are said to be “border adjustable.” And here’s Krugman’s caustic observation about the above argument.

I’ve been writing about Donald Trump’s claim that Mexico’s value-added tax is an unfair trade policy, which is just really bad economics. …a VAT has the same effects as a sales tax. Now, nobody thinks that sales taxes are an unfair trade practice. …Trump wasn’t saying ignorant things off the top of his head: he was saying ignorant things fed to him by his incompetent economic advisers. …Should we be reassured that Trump wasn’t actually winging it here, just taking really bad advice? Not at all.

I don’t know whether it’s fair to criticize Trump’s economic advisers (after all, are they the ones who developed this position, or were they simply told to justify what Trump was saying?), but I certainly agree with Krugman that other nations don’t gain a trade advantage simply because they have a VAT.

Here’s some of what I wrote about this issue earlier this year.

For mercantilists worried about trade deficits, “border adjustability” is seen as a positive feature. But not only are they wrong on trade, they do not understand how a VAT works. …Under current law, American goods sold in America do not pay a VAT, but neither do German-produced goods that are sold in America. Likewise, any American-produced goods sold in Germany are hit be a VAT, but so are German-produced goods. In other words, there is a level playing field. The only difference is that German politicians seize a greater share of people’s income. So what happens if America adopts a VAT? The German government continues to tax American-produced goods in Germany, just as it taxes German-produced goods sold in Germany. …In the United States, there is a similar story. There is now a tax on imports, including imports from Germany. But there is an identical tax on domestically-produced goods. And since the playing field remains level, protectionists will be disappointed. The only winners will be politicians since they have more money to spend.

If you want more information, I also discuss the trade impact of a VAT in this video.

So, yes, Krugman is right. At least on this particular issue.

Actually, he’s even right about another part of his column, when he pointed out that if a VAT is supposedly good for competitiveness, then this should give New York (with a high sales tax) an advantage over Delaware (with no sales tax). As Krugman points out, this is absurd.

…nobody thinks that sales taxes are an unfair trade practice. New York has fairly high sales taxes; Delaware has no such tax. Does anyone think that this gives New York an unfair advantage in interstate competition?

Indeed, the answer to Krugman’s rhetorical question is that lots of people recognize that Delaware has the advantage. This is why politicians in many states (especially those with punitive sales taxes) are pushing for the so-called Marketplace Fairness Act in hopes of forcing merchants in states like Delaware to become deputy tax collectors for states like New York (this would be an odious expansion of extraterritorial tax powers for state governments).

I don’t want to get all wonky, but this fight revolves around whether consumption taxes should be levied where goods and services are sold (the origin-based approach) or whether the taxes should be collected based on where the consumer lives (the destination-based approach). High-tax governments prefer the latter because they want to make it difficult for their residents to shop where the tax burden is lower.

By the way, politicians in Europe and elsewhere impose destination-based VATs for the same reason. They don’t like tax competition. So that’s yet another reason (above and beyond the fact that they are money machines for big government) to dislike the VAT.

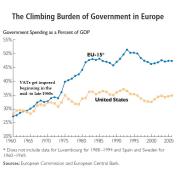

By the way, politicians in Europe and elsewhere impose destination-based VATs for the same reason. They don’t like tax competition. So that’s yet another reason (above and beyond the fact that they are money machines for big government) to dislike the VAT.

I suspect, incidentally, that Krugman favors destination-based consumption taxes over origin-based systems, so even though he’s right about VATs and trade, he probably compensates by being wrong on an issue that really matters.