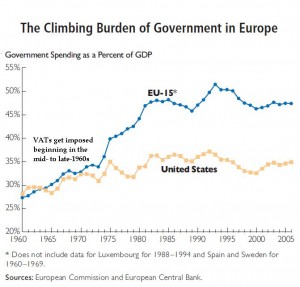

The value-added tax is a very dangerous levy for the simple reason that giving a big new source of revenue to Washington almost certainly would result in a larger burden of government spending.

That’s certainly what happened in Europe, and there’s even more reason to think it would happen in America because we have a looming, baked-in-the-cake entitlement crisis and many  politicians don’t want to reform programs such as Medicare,Medicaid, and Obamacare. They would much rather find additional tax revenues to enable this expansion of the welfare state. And their target is the middle class, which is why they very much want a VAT.

politicians don’t want to reform programs such as Medicare,Medicaid, and Obamacare. They would much rather find additional tax revenues to enable this expansion of the welfare state. And their target is the middle class, which is why they very much want a VAT.

The most frustrating part of this debate is that there are some normally rational people who are sympathetic to the VAT because they focus on theoretical issues and somehow convince themselves that this new levy would be good for the private sector.

Here are the four most common economic myths about the value-added tax.

Myth 1: The VAT is pro-growth

Reihan Salam implies in the Wall Street Journal that taxing consumption is good for growth.

Mr. Cruz has roughly the right idea. He has come out in favor of a growth-friendly tax on consumption… Rather sneakily, he’s calling his consumption tax a “business flat tax,” but everyone knows that it’s a VAT.

And a different Wall Street Journal report asserts there’s a difference between taxing income and taxing consumption.

…a VAT taxes what people consume rather than how much they earn.

Reality: The VAT penalizes all productive economic activity

I don’t care whether proponents change the name of the VAT, but they are wrong when they say that taxes on consumption are somehow better for growth than taxes on income. Consider two simple scenarios. In the first example, a taxpayer earns $100 but loses $20 to the income tax. In the second example, a taxpayers earns $100, but loses $20 to the VAT. In one case, the taxpayer’s income is taxed when it is earned and in the other case it is taxed when it is spent. But in both cases, there is an identical gap between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. The economic damage is identical, with the harm rising as the marginal tax rate (either income tax rate or VAT rate) increases.

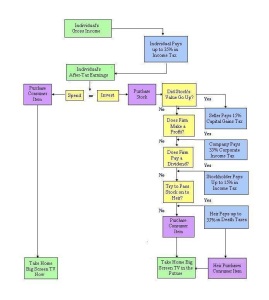

Advocates for the VAT generally will admit that this is true, but then switch the argument and say that there’s pervasive double taxation in the internal revenue code and that this tax bias against saving and investment does far more damage, per dollar collected, than either income taxes imposed on wages or VATs imposed on consumption.

Advocates for the VAT generally will admit that this is true, but then switch the argument and say that there’s pervasive double taxation in the internal revenue code and that this tax bias against saving and investment does far more damage, per dollar collected, than either income taxes imposed on wages or VATs imposed on consumption.

They’re right, but that’s an argument against double taxation, not an argument for taxing consumption instead of taxing income. They then sometimes assert that a VAT is needed to make the numbers add up if double taxation is to be eliminated. But a flat tax does the same thing, and without the risk of giving politicians a new source of revenue.

Myth 2: The VAT is pro-savings and pro-investment

As noted in a recent Wall Street Journal story, advocates claim this tax is an economic elixir.

Supporters of a VAT…say it is better for economic growth than an income tax because it doesn’t tax savings or investment.

Reality: The VAT discourages saving and investment

The superficially compelling argument for this assertion is that the VAT is a tax on consumption, so the imposition of such a tax will make saving relatively more attractive. But this simple analysis overlooks the fact that another term for saving is deferred consumption. It is true, of course, that people who save usually earn some sort of return (such as interest, dividends, or capital gains). This means they will be able to enjoy more consumption in the future. But that does not change the calculation. Instead, it simply means there will be more consumption to tax. In other words, the imposition of a VAT does not alter incentives to consume today or consume in the future (i.e., save and invest).

But this is not the end of the story. A VAT, like an income tax or payroll tax, drives a wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax income. This means, as already noted above, that a VAT also drives a wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption – and this is true for current consumption and future consumption. This tax wedge means less incentive to earn income, and if there is less total income, this reduces both total saving and total consumption.

Again, advocates of a VAT generally will admit this is correct, but then resort to making a (correct) argument against double taxation. But why take the risk of a VAT when there are very simple and safe ways to eliminate the tax bias against saving and investment.

Myth 3: The VAT is pro-trade.

My normally sensible friend Steve Moore recently put forth this argument in the American Spectator.

…a better way to do this…is through a “border adjustable”…tax, meaning that it taxes imports and relieves all taxes on exports. …The guy who gets this is Ted Cruz. His tax plan…would not tax our exports. Cruz is right when he says this automatically gives us a 16% advantage.

Reality: The protectionist border-adjustability argument for a VAT is bad in theory and bad in reality.

For mercantilists worried about trade deficits, “border adjustability” is seen as a positive feature. But not only are they wrong on trade, they do not understand how a VAT works. Protectionists seem to think a VAT is akin to a tariff. It is true that the VAT is imposed on imports, but this does not discriminate against foreign-produced goods because the VAT also is imposed on domestic-produced goods.

Under current law, American goods sold in America do not pay a VAT, but neither do German-produced goods that are sold in America. Likewise, any American-produced goods sold in Germany are hit be a VAT, but so are German-produced goods. In other words, there is a level playing field. The only difference is that German politicians seize a greater share of people’s income.

So what happens if America adopts a VAT? The German government continues to tax American-produced goods in Germany, just as it taxes German-produced goods sold in Germany. There is no reason to expect a VAT to cause any change in the level of imports or exports from a German perspective. In the United States, there is a similar story. There is now a tax on imports, including imports from Germany. But there is an identical tax on domestically-produced goods. And since the playing field remains level, protectionists will be disappointed. The only winners will be politicians since they have more money to spend.

I explain this issue in greater detail in this video, beginning about 5:15, though I hope the entire thing is worth watching.

Myth 4: the VAT is pro-compliance

There’s a common belief, reflected in this blurb from a Wall Street Journal report, that a VAT has very little evasion or avoidance because it is self enforcing.

…governments like it because it tends to bring in more revenue, thanks in part to the role that businesses play in its collection. Incentivizing their efforts, businesses receive credits for the VAT they pay.

Reality: Any burdensome tax will lead to avoidance and evasion and that applies to the VAT.

I’m always amused at the large number of merchants in Europe who ask for cash payments for the deliberate purpose of escaping onerous VAT impositions. But my personal anecdotes probably are not as compelling as data from the European Commission.

To give an idea of the magnitude, here are some excerpts from a recent Bloomberg report.

Over the next two years, the Brussels-based commission will seek to streamline cross-border transactions, improve tax collection on Internet sales… In 2017, the EU plans to propose a single European VAT area, a reform of rates and add specifics to its anti-fraud strategy. …“We face a staggering fiscal gap: the VAT revenues are 170 billion euros short of what they could be,” EU Economic Affairs and Tax Commissioner Pierre Moscovici said. “It’s time to have this money back.”

For what it’s worth, the Europeans need to learn that burdensome levels of taxation will always encourage noncompliance.

Though, to be fair, much of the “tax gap” for the VAT in Europe exists because governments have chosen to adopt “destination-based” VATs rather than “origin-based” VATs, largely for the (ineffective) protectionist reasons outlined in Myth 3. And this creates a big opportunity to escape the VAT by classifying sales as exports, even if the goods and services ultimately are consumed in the home market.

P.S. At the risk of being wonky, it should be noted that there are actually two main types of value-added tax. In both cases, businesses collect the tax, and the tax incidence is similar (households actually bear the cost), but there are different collection methods. The credit-invoice VAT is the most common version (ubiquitous in Europe, for instance), and it somewhat resembles a sales tax in its implementation, albeit with the tax imposed at each stage of the production process. The subtraction-method VAT, by contrast, relies on a tax return sort of like the corporate income tax. The Joint Committee on Taxation has a good description of these two systems.

Under the subtraction method, value added is measured as the difference between an enterprise’s taxable sales and its purchases of taxable goods and services from other enterprises. At the end of the reporting period, a rate of tax is applied to this difference in order to determine the tax liability. The subtraction method is similar to the credit-invoice method in that both methods measure value added by comparing outputs (sales) to inputs (purchases) that have borne the tax. The subtraction method differs from the credit-invoice method principally in that the tax rate is applied to a net amount of value added (sales less purchases) rather than to gross sales with credits for tax on gross purchases (as under the credit-invoice method). The determination of the tax liability of an enterprise under the credit-invoice method relies upon the enterprise’s sales records and purchase invoices, while the subtraction method may rely upon records that the taxpayer maintains for income tax or financial accounting purposes.

P.P.S. Another wonky point is that the effort by states to tax Internet sales is actually an attempt to implement and enforce the kind of “destination-based” tax regime mentioned above. I explain that issue in this presentation on Capitol Hill.