Maybe future events will require a reassessment, but right now the biggest danger to the western world isn’t terrorism. Nor is it climate change. Or Zika. Or even Donald Trump.

The real threat is demographic change.

America’s population profile already has changed, but the future shift will be even more dramatic.

But demographics changes are neither good nor bad. The real problem, as I pointed out last month, is when you combine an aging population with poorly designed entitlement programs.

…even a small welfare state becomes a problem when a nation has a population cylinder. Simply stated, there aren’t enough people to pull the wagon and there are too many people riding in the wagon.

That’s a recipe for a crisis.

Here are some sobering details from a story in Business Insider.

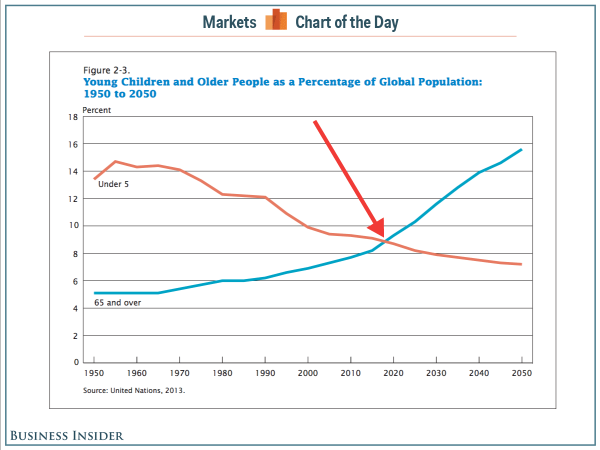

The world is about to see a mind-blowing demographic situation that will be a first in human history: There are about to be more elderly people than young children. …And these two age groups will continue to grow in opposite directions: The proportion of the population ages 65 and up will continue to increase, while the proportion of the population ages 5 and under will continue decreasing. In fact, according to the Census Bureau, by 2050 those ages 65 and up will make up an estimated 15.6% of the global population — more than double that of children ages 5 and under, who will make up an estimated 7.2%. “This unique demographic phenomenon of the ‘crossing’ is unprecedented,” the report’s authors said.

Here’s the chart that accompanied the story.

And as you look at the numbers, keep in mind that entitlement programs mean that a growing population of old people means more spending, while a shrinking number of children means fewer future taxpayers to finance that spending.

Let’s now look at a nation that is the “canary in the coal mine” for why changing demographics is a recipe for fiscal crisis.

A story from The Week highlights the grim demographic outlook for Japan.

Japan is us, and we’re Japan. …Japan has a…serious problem on its hands: The country is literally dying. According to current projections, by 2060 the country will have shrunk by a third, and people over 65 years old will account for 40 percent of the population. Already, the country is selling more adult diapers than infant diapers. To say this is unsustainable is a euphemism. The country is quite simply dying. …Demography is not destiny, exactly, but it is close to it. …the impending collapse can no longer be denied, as is the case in Japan and Germany. …The extinction of a people and culture is always a global tragedy. It’s time for Japan — and the West — to wake up.

A wake-up call is needed. It’s not just Japan. The entire developed world faces a demographic problem.

The good news is that there is an understanding that something needs to change.

The not-so-good news is that many of the responses are misguided. Cheered on by the OECD, Japan has been boosting the value-added tax in hopes of financing an ever-expanding burden of government spending.

That won’t end well.

And I’m not overly enthralled by some of the other proposals.

Why not just pay people to have children? …If you lower the price of something, you will get more of it. Over the past two decades, Japan has spent trillions of dollars on mostly wasteful pork-barrel spending projects. It seems to me that the country would be better off today if that money had been spent on bonuses for second and third children instead.

For what it’s worth, I agree that giving money to parents would have been better than the various Keynesian spending binges (some of which are downright nuts) that have taken place in Japan.

But I’m not confident that child subsidies are an effective or desirable long-run solution to the nation’s demographic situation.

The one option that would work is to reform entitlement programs. Hong Kong’s demographic outlook is even more challenging than Japan’s, yet it is in much better long-run shape because it has a more sensible approach to entitlements, including a private Social Security system.

———

Image credit: Pedro Ribeiro Simões | CC BY 2.0.