During the election, Donald Trump promised a big package of infrastructure spending, twice as much new spending as Hillary Clinton was proposing.

During his victory speech the night of the election, he doubled down on this approach, promising that more infrastructure spending would be one his first priorities.

This sounds like bad news for advocates of limited government. And it may turn out to be bad news. Though if you look at what the Trump campaign actually proposed, there’s a lot of wiggle room.

I will work with Congress to introduce the following broader legislative measures and fight for their passage within the first 100 days of my Administration: …American Energy & Infrastructure Act. Leverages public-private partnerships, and private investments through tax incentives, to spur $1 trillion in infrastructure investment over 10 years. It is revenue neutral.

In other words, it’s possible that President-Elect Trump might give us an Obama-style stimulus scheme. Or he may take a radically different approach by removing roadblocks that hinder more private-sector involvement.

And my colleague Chris Edwards points out that the private sector already does most of the heavy lifting when it comes to infrastructure spending.

Hillary Clinton says that “we are dramatically underinvesting” in infrastructure and she promises a large increase in federal spending. Donald Trump is promising to spend twice as much as Clinton. …But more federal spending is the wrong way to go. …let’s look at some data. There is no hard definition of “infrastructure,” but one broad measure is gross fixed investment in the BEA national accounts. …The first thing to note is that private investment at about $3 trillion was six times larger than combined federal, state, and local government nondefense investment of $472 billion. Private investment in pipelines, broadband, refineries, factories, cell towers, and other items greatly exceeds government investment in schools, highways, prisons, and the like. …if policymakers want to boost infrastructure spending, they should reduce barriers to private investment.

This is very helpful and interesting data. And one of the obvious conclusions is that the types of infrastructure that historically are the responsibility of the private sector (pipelines, cell towers, etc) are handled much more efficiently than those (highways, mass transit, etc) that have been monopolized by governments.

Trump presumably intends his infrastructure plan to focus on the latter type of infrastructure, so let’s consider three simple rules to help guide an effective approach for transportation.

1. More private-sector involvement

A key principle for good infrastructure policy is to harness the efficiency of the private sector.

Why? Because, as Lawrence McQuillan of the Independent Institute argues, governments naturally are inefficient and incompetent at building and managing infrastructure.

Government authorities view maintenance solely as a cost, rather than as an investment that can increase future revenues. As a result, roads remain riddled with potholes, bridges crumble, airports are overcrowded, water is contaminated, and we have classrooms with mold and falling ceilings. Moreover, without a profit motive, repairs are seldom done in a timely manner or at lowest cost. Instead of assets being owned and controlled by people who understand the economics of the industry and have the technical knowledge to operate and repair them efficiently, politicians (the majority of whom appear to be lawyers these days) and bureaucrats control them. This guarantees waste, inefficiency and cronyism, such as the greenlighting of white-elephant projects that are driven by politics rather than economics.

But there is some good news.

Chris Edwards explains that the private sector is taking a larger role.

Before the 20th century, for example, more than 2,000 turnpike companies in America built more than 10,000 miles of toll roads. And up until the mid-20th century, most urban rail and bus services were private. With respect to railroads, the federal government subsidized some of the railroads to the West, but most U.S. rail mileage in the 19th century was in the East, and it was generally unsubsidized. The takeover of private infrastructure by governments here and abroad in the 20th century caused many problems. Fortunately, most governments have reversed course in recent decades and started to hand back infrastructure to the private sector. …Short of full privatization, many countries have partly privatized portions of their infrastructure through public-private partnerships (“PPPs” or “P3s”). PPPs differ from traditional government contracting by shifting various elements of financing, management, maintenance, operations, and project risks to the private sector. …Unfortunately, the United States “has lagged behind Australia and Europe in privatization of infrastructure such as roads, bridges and tunnels,” notes the OECD. More than one fifth of infrastructure spending in Britain and Portugal is now through the PPP process, so this has become a normal way of doing business in some countries. Canada is also a leader in using PPP for major infrastructure projects.

2. Less involvement from Washington

To the extent that government must be involved, another important principle is to let state and local governments handle infrastructure.

That’s what I argued back in 2014.

…the Department of Transportation should be dismantled for the simple reason that we’ll get better roads at lower cost with the federalist approach of returning responsibility to state and local governments. …Washington involvement is a recipe for pork and corruption. Lawmakers in Congress – including Republicans – get on the Transportation Committees precisely because they can buy votes and raise campaign cash by diverting taxpayer money to friends and cronies. …the federal budget is mostly a scam where endless streams of money are shifted back and forth in leaky buckets. This scam is great for insiders and bad news for taxpayers. Washington involvement necessarily means another layer of costly bureaucracy. And this is not a trivial issues since the Department of Transportation is infamous for overpaid bureaucrats.

For a more detailed explanation, Professor Edward Glaeser of Harvard has some devastating analysis in an article for City Journal.

The most pressing problem with federal infrastructure spending is that it is hard to keep it from going to the wrong places. We seem to have spent more in the places that already had short commutes and less in the places with the most need. Federal transportation spending follows highway-apportionment formulas that have long favored places with lots of land but not so many people. …Low-density areas are remarkably well-endowed with senators per capita, of course, and they unsurprisingly get a disproportionate share of spending from any nationwide program. Redirecting tax dollars across jurisdictions is rarely fair—and it isn’t right, either, that poorer, lower-density regions should subsidize New York’s subway and airports. Washington’s involvement also distorts infrastructure planning by favoring pet projects. The Recovery Act set aside $8 billion for high-speed rail, for instance, despite the fact that such projects would never be appropriate for most of moderate-density America. California was lured down the high-speed hole with Washington support… Detroit’s infamous People Mover Monorail would never have been built without federal aid. Alaska’s $400 million Gravina Island bridge to nowhere was a particularly notorious example of how Congress abuses transportation investment. As the Office of Management and Budget noted, during the Bush years, highway funding was “not based on need or performance and has been heavily earmarked.”

3. Sensible cost-benefit analysis

Our third principle is that infrastructure should only be built if it makes sense. In other words, do the benefits exceed the costs?

In the private sector, the profit motive automatically generates that type of calculation.

With government, that effort becomes much more challenging.

Professor Michael Boskin at Stanford explains the problem in a column for the Wall Street Journal.

…a huge pot of additional money earmarked for infrastructure, on top of the recently passed $305 billion five-year highway bill, is sure to unleash a mad scramble in Congress to secure funds for the home turf. The logrolling and pork will get ugly without far tighter cost-benefit tests and oversight. …Most federal infrastructure spending is done by sending funds to state and local governments. For highway programs, the ratio is usually 80% federal, 20% state and local. But that means every local district has an incentive to press the federal authorities to fund projects with poor national returns. We all remember Alaska’s infamous “bridge to nowhere.” In other words, if a local government is putting up only 20% of the funds, it needs the benefits to its own citizens to be only 21% of the total national cost. Yet every state and every locality has potential infrastructure needs that it would like the rest of the country to pay for. That leads to the misallocation of federal funds and infrastructure projects that benefit the few at the cost of the many. …taxpayers generally don’t notice all the fiscal cross-hauling, sending their money to Washington to be sent back in leaky buckets to local jurisdictions. Since we all reside in a state and locality, it’s an inefficient negative sum game with complex cross-subsidies. If these local projects are so good, why aren’t citizens willing to finance the projects locally?

And don’t forget government infrastructure always is more expensive – sometimes far more expensive – than politicians first promise. Chris Edwards has the details.

Federal infrastructure projects often suffer from large cost overruns. Highway projects, energy projects, airport projects, and air traffic control projects have ended up costing far more than promised. When both federal and state governments are involved in infrastructure, it reduces accountability. That was one of the problems with the federally backed Big Dig highway project in Boston, which exploded in cost to five times the original estimate. U.S. and foreign studies have found that privately financed infrastructure projects are less likely to have cost overruns.

The challenge, of course, is getting governments to produce honest cost-benefit analysis. Bureaucrats respond to the people who control their jobs and control their pay. So if politicians want to squander more money, it’s quite likely that bureaucrats will concoct the numbers needed to justify the expansion of government.

To cite a high-profile example, I caught the IMF making up numbers to justify infrastructure boondoggles, even though that politically driven analysis contradicted the work of the bureaucracy’s professional economists.

Let’s finish with two additional points.

First, advocates of more infrastructure spending act like there’s some national crisis.

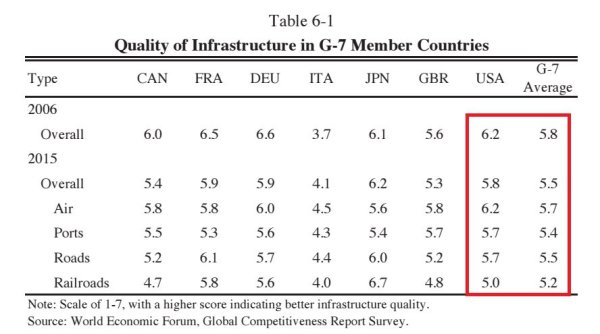

But if this is true, why does the United States get relatively high scores from the World Economic Forum?

Second, let’s consider the example of Japan. That nation has been stuck in a multi-decade period of stagnation, with very little expectation of an economic turnaround. But if infrastructure spending was some sort of elixir, that economy should be booming.

…a look at ailing Japan, which has spent over $6.3 trillion since 1981 on truly impressive bridges and bullet trains, suggests infrastructure isn’t always a cure for economic woes.

The bottom line is that Donald Trump should not follow the business-as-usual approach of simply dumping more money into a system that almost always produces poor results.