George Santayana was certainly was right when he wrote, “Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” Consider, for instance, the foolish American politicians who want to rejuvenate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and other forms of housing subsidies even though we’re still dealing with the havoc of the last government-created housing bubble.

Though when Italian politicians fail to learn to from history, do it on a bigger and bolder scale.

We’ll start by going back a couple of millennia. Larry Reed of the Foundation for Economic Education tells the story of how Ancient Rome disintegrated thanks to the welfare state.

More than 2,000 years before America’s bailouts and entitlement programs, the ancient Romans experimented with similar schemes. The Roman government rescued failing institutions, canceled personal debts, and spent huge sums on welfare programs. The result wasn’t pretty. …these expensive rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul efforts were major factors in bankrupting Roman society. They inevitably led to even more destructive interventions. Rome wasn’t built in a day, as the old saying goes — and it took a while to tear it down as well. Eventually, when the republic faded into an imperial autocracy, the emperors attempted to control the entire economy.

In reading Larry’s article, I learned about many awful politicians from ancient times.

But if I had to identify the Roman version of Barack Obama, Larry makes a persuasive case that it would be Tiberius Gracchus.

By 133 BC, the up-and-coming politician Tiberius Gracchus…passed a bill granting free tracts of state-owned farmland to the poor. Additionally, the government funded the erection of their new homes and the purchase of their farming tools. …Tiberius, incidentally, also passed Rome’s first subsidized food program, which provided discounted grain to many citizens. Initially, Romans dedicated to the ideal of self-reliance were shocked at the concept of mandated welfare, but before long, tens of thousands were receiving subsidized food, and not just the needy. Any Roman citizen who stood in the grain lines was entitled to assistance.

Sure enough, more and more Romans over time learned that it was more fun to ride in the wagon rather than pull it.

…at its peak, a third of Rome took advantage of the program. It became a hereditary privilege, passed down from parent to child. Other foodstuffs, including olive oil, pork, and salt, were regularly incorporated into the dole. The program ballooned until it was the second-largest expenditure in the imperial budget, behind the military.

So what’s the moral of this story?

Larry’s article shows that my Theorem of Societal Collapse has a long history.

The Roman experience teaches important lessons. As the 20th-century economist Howard Kershner put it, “When a self-governing people confer upon their government the power to take from some and give to others, the process will not stop until the last bone of the last taxpayer is picked bare.” Putting one’s livelihood in the hands of vote-buying politicians compromises not just one’s personal independence, but the financial integrity of society as well. The welfare state, once begun, is difficult to reverse and never ends well. Rome fell to invaders in 476 AD, but who the real barbarians were is an open question. …Maybe the real barbarians were those Romans who had effectively committed a slow-motion financial suicide.

In any event, Italy slipped into the dark ages.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that Italy also helped Europe recover from the dark ages. There was no unified nation at the time, but city states such as Genoa and Venice became major trading hubs.

Indeed, private money actually first evolved in the Italian city states.

Over several hundred years, modern Italy came into being, and that occurred during a period when government was constrained. Indeed, it’s worth noting that there wasn’t an income tax until the 1860s.

And Italy had less redistribution than the United States as late as 1930.

So there was a period where government was reasonably small and Italy enjoyed some degree of prosperity.

Unfortunately, once modern-era welfare-state programs were adopted, growth was negatively impacted. And now it’s disappeared entirely, as noted in an article by Alessio Terzi for Bruegel.

Italy…is the only EU member state, together with Greece, where real GDP is now below its 2000 level. …Moreover, Italy’s longstanding vulnerabilities such as its mammoth public debt – second only to Greece’s in GDP terms – …could easily derail the recovery.

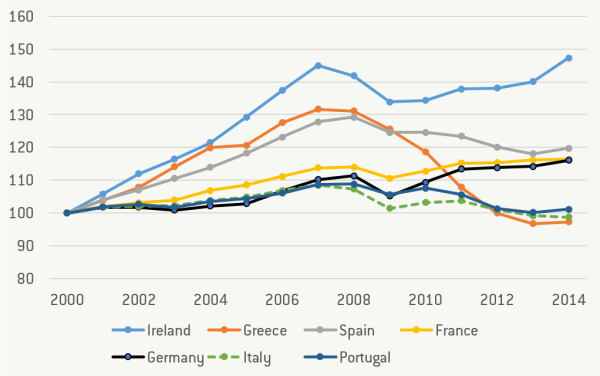

Here’s a very depressing chart (if you’re Italian, or even if you merely care about Italy) showing that economic output today is lower than it was in 2000.

The only silver lining to this bad news is that the Italians presumably have less reason to be upset than the Greeks.

Sure, both nations have enjoyed zero growth in the 21st Century, but the Greeks went through an illusory period where they thought they had growth.

So it probably is even more painful to them now that they’ve taken a tumble.

By the way, Alessio’s article actually speculates that Italy may be poised for an economic rebound.

I hope that’s correct, and the article does mention a few reforms, but I’m not overly optimistic.

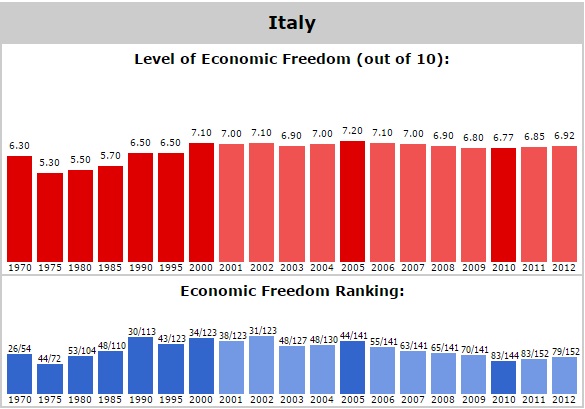

Check out the country’s ranking from Economic Freedom of the World.

As you can see, Italy ranks only 79 out of 152.

To be sure, that means there’s a lot of room to climb. But does anyone expect Italy to become Switzerland on the Mediterranean?

Heck, at least one Italian region is so dour about the nation’s outlook that it’s petitioning to be annexed by Switzerland!

Italy’s lowest grade in Economic Freedom of the World is for fiscal policy. And since government spending consumes a bit more than half the nation’s economic output, you can understand why there’s so little activity in the private sector.

Especially when you consider that excessive government spending results in punitive tax policy.

Here’s another reason to be pessimistic. Italy’s demographic profile is terrible. I’ve previously explained that even a nation with a medium-sized welfare state is in deep trouble if its population profile begins to resemble a cylinder rather than a pyramid.

Well, that’s happening to Italy, except it has a large welfare state rather than a medium-sized one.

So there’s not much reason for hope.

P.S. Allow me to rephrase something. I wrote above that “Italy’s demographic profile is terrible.” That’s not actually accurate. There’s nothing a priori wrong with women deciding to have fewer children. And it’s unambiguously good news that people are living longer. What I should have written is that Italy’s long-run fiscal outlook is terrible. And the reason for that grim situation is the combination of demographics and redistribution programs.

P.P.S. As a general rule, demographics is destiny. At least in most advanced nations. The exceptions are jurisdictions such as Hong Kong and Singapore. By the way, both have aging populations and extremely low birthrates (Singapore in last place out of 224 nations and Hong Kong third from the bottom). But because they have very low levels of redistribution, both jurisdictions are well positioned to deal with changing demographics.