I’ve written (some would say excessively) about the fact that America has too many bureaucrats and that they’re paid too much.

That’s true in Washington. That’s true at the state level. And it’s true for local governments.

But since I’m a big believer in beating a dead horse, let’s revisit this issue. We’ll narrow our focus today and look solely at the issue of retirement benefits for state and local bureaucrats.

Why? Because, as explained by Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute, the unfunded liability for these schemes has mushroomed into a giant $5 trillion problem.

If the Actuarial Standards Board enacts recommendations from its Pension Task Force, actuarial valuations for state and local government pensions will report unfunded liabilities of over $5 trillion and funding ratios of just 39 percent. The public pensions industry will hate it, but those figures are the best available measures of the costs of public employee retirement plans. …That $5.2 trillion is the number most economists would think is most relevant to considering the costs of public sector pensions. …The simple reality is that public pension underfunding is a significant problem that can only really be addressed by increasing contributions or by lower pension benefits, choices that pretty much everyone involved in the pension world would prefer to avoid.

You won’t be surprised to learn that some states are more irresponsible than others.

CNBC reports that Nebraska is the most prudent and Alaska is the worst (politicians can’t resist squandering oil revenue). Several blue states rank poorly (think Illinois, Connecticut, California, and New Jersey), but there also are red states (such as Louisiana and Kentucky) that have made very foolish promises.

In Nebraska, for example, the pension liability amounts to about $386 per person, the lowest in the nation. That compares with Alaska ($19,394 per person: the highest in the country), Illinois ($15,158 per person) and Connecticut ($14,769). The average pension shortfall in 2014 amounted to $4,383.

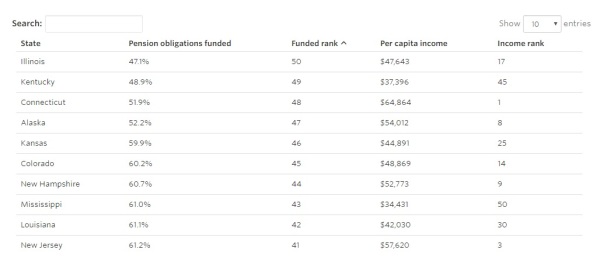

The Wall Street Journal has an interactive table that allows readers to see which states have the biggest shortfall.

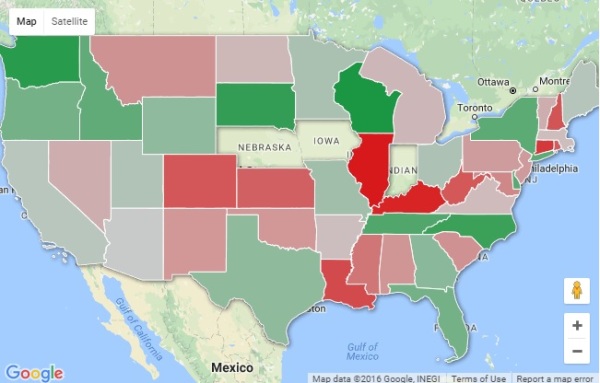

Meanwhile, Governing has an interactive map showing which states have the biggest gaps.

In other words, state and local bureaucrats have been promised a lot of money when they retire.

Much more money than is available.

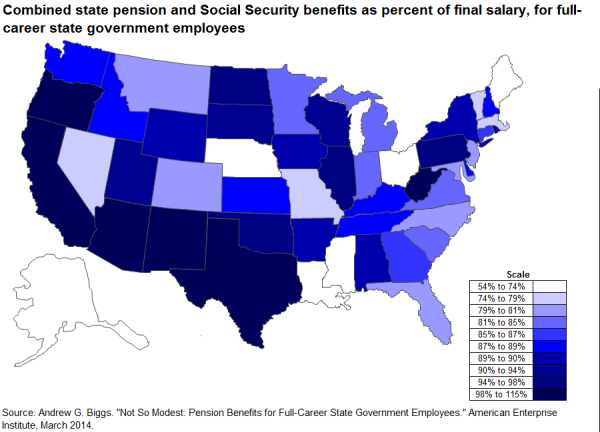

And when you add Social Security benefits to the mix, as Andrew Biggs has calculated, you wind up having lots of bureaucrats enjoying very lavish levels of retirement income.

I tabulated the pension benefits paid to full-career “regular” state government employees (meaning, non-public safety) retiring in 2012. For states in which public employees participated in Social Security, I estimated the Social Security benefit the retiree would be eligible to receive. And finally, I compared total retirement benefits to the worker’s earnings immediately preceding retirement. …Mississippi paying the lowest replacement rate of 54% of final earnings. …West Virginia paid the most generous benefits, equal to 115% of final earnings, followed by New Mexico (113%), Oregon (105%), California (102%) and, yes, conservative Texas (101%).

Here’s a map that accompanied the article.

But maybe big numbers, maps and tables are too abstract.

To give some examples of how this is leading to a fiscal crisis, consider these recent news reports.

A story from the Las Vegas Review-Journal:

Nevadans should brace for reduced services, higher taxes or both — the necessary consequence of the Public Employee Retirement System of Nevada (PERS) having badly missed its investment target last year…PERS has now missed its target over the past five, 10, 15, 20 and 25 years — suggesting that another taxpayer-rate hike is on its way. Remarkably, this shortfall has occurred even though markets have nearly tripled from their 2009 lows, and currently sit at or near all-time highs. Nevada’s soaring pension costs — ranked third-highest in the nation at 9.8 percent of own-source revenue, according to 2013 data from the Public Plans Database — aren’t just due to overly optimistic investment assumptions, however. Another factor is the extraordinarily generous nature of the benefits.

A column from the Orange County Register:

…in the world of public sector pensions – among the biggest institutional investors in global markets – politicians…pretend they can count on big investment returns every year, while disregarding warning signs, mounting debts and increasingly unsustainable pension systems. We’re seeing the latest pension fund returns come in, and almost uniformly, it was a terrible year for states – and thus taxpayers. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the largest U.S. public pension fund, logged a paltry annual return of 0.6 percent. …CalPERS is currently only 76 percent funded, a figure that will inevitably drop given the latest weak returns.

A report from the Portland Tribune:

Oregon’s major business groups want lawmakers to start dealing with rising public pension costs as early as the session that opens Feb. 1. Although those costs start to kick in with the 2017-19 budget cycle — 18 months away — advocates say it’s not too early to whittle down an unfunded liability projected at $18 billion over the next few decades. …projected increases in contributions to PERS, which covers about 95 percent of Oregon’s public workers, will eat deeply into what they can spend over the next several two-year budget cycles. Cheri Helt, co-chair of the Bend-La Pine School Board, says pension costs will jump from the current 16 percent of payroll to 20 percent in 2017-19, and to 25 percent in the cycle afterward. …Jamie Moffitt, vice president and chief financial officer for the University of Oregon, says rising pension costs will eat up 40 percent — about 2 percentage points — of the 5.5 percent average annual increase in tuition.

An editorial about New Jersey in the Wall Street Journal:

New Jersey’s Senate president is in a Brando-like fight with government unions that he says are trying to extort or bribe legislators into doing their bidding. …At issue is the woefully underfunded state pension system. The teachers union wants to put a measure on the November ballot to amend the state constitution to require quarterly state pension payments of increasing amounts. …government unions have so much political sway over politicians that they often call the shots on their own pensions and benefits. …New Jersey’s public pensions are underfunded to the tune of $82 billion. Thomas Healey of the state’s bipartisan Pension and Health Benefit Study Commission notes that pensions and health care now eat up 11% of New Jersey’s budget, and without reform this will grow to 28% by 2025. …The pension commission has proposed reforms—including a shift to a hybrid retirement plan that includes features more akin to a 401(k)—but unions have blocked them. They now want voters to rewrite the state constitution so pension reform would be all but impossible.

A column about the corrupt system in Illinois:

Illinois’s government, says [Gov.] Rauner, “is run for the benefit of its employees.” Increasingly, it is run for their benefit when they retire. Pension promises [are] unfunded by at least $113 billion… The government is so thoroughly unionized (22 unions represent almost all government employees), that “I can’t,” Rauner says, “turn on a light switch without permission.” He exaggerates, somewhat, but the process of trying to fire someone is a career, not an option. …high-tax Illinois will continue bleeding population and businesses, but with one contented cohort — the Democratic political class, for whom the system is working quite well.

The crux of the problem is that most state and local governments have “defined-benefit” plans for bureaucrats, which means that taxpayers are on the hook to provide retiring bureaucrats a specific amount of benefits (not just retirement income, but other goodies such as health care) based on formulas that count years in the workforce, highest salary levels, and other factors. That may not sound totally unreasonable, but politicians realize they can buy votes by cutting deals with government unions and providing retirement benefits that are extremely generous, especially compared to what’s available for workers in the private sector.

But that’s simply one part of the problem. The other part of the problem is the employers with defined-benefit plans (usually referred to as “DB plans”) are supposed to set aside money in investment funds so that there’s a growing pool of assets that can be used to pay for the lavish benefits promised to the bureaucracy. But as we’ve already learned, politicians often are reluctant to take this step. They like committing lots of future money to bureaucrats, but when putting together annual budgets, they generally can buy more votes by allocating money to things like schools and roads rather than depositing money into a pension fund.

So the net result is that there’s a big unfunded liability, meaning that the amount that politicians have promised to give bureaucrats is larger than what’s set aside in the pension funds. And to make matters worse, the pension funds usually have dodgy accounting (they assume the investments will earn more money than is realistic). Which is why the actual shortfall is about $5.2 trillion, as noted above.

Given this ticking time bomb, some of you may be wondering why the title says there’s a libertarian quandary. Surely the answer is to cauterize this fiscal wound with immediate cuts and to avoid an even bigger long-run disaster by shifting newly hired bureaucrats to a defined-contribution system such as IRAs or 401(k)s. This type of reform automatically eliminates any liability for taxpayers since retirement benefits for bureaucrats would be solely a function of contributions to retirement accounts and the investment performance of those funds (most state and local bureaucrats also are part of the Social Security system).

Yes, that is the answer, but the quandary (to add to my collection) is whether the federal government should force, or even encourage, this type of reform. Don’t state and local governments, after all, have the right to make stupid decisions?

Writing for the Wall Street Journal, Ed Bachrach argues that Uncle Sam should limit these suicidal policies.

The pensions of states and local governments are, collectively, trillions of dollars in the hole. This debt is crippling budgets and will dump an enormous burden on future generations. Yet state and local politicians have proven that they cannot, or will not, solve the problem. The federal government ought to step in. But how? Instead of bailing out these pensions, Congress should pass a law allowing states and local governments to reduce promised benefits—something that is now illegal under some states’ statutes or constitutions. …Many pensions allow retirement at age 55; states and local governments could mandate that benefits cannot be drawn until age 65. Payments could be capped at 150% of the median income in the local jurisdiction. Automatic cost-of-living increases that now exceed expected inflation could instead be tied to increases in the median income. …Local governments must also be required to terminate their defined-benefit plans. These should be replaced with defined-contribution plans, like 401(k)s or 403(b)s… Rep. Devin Nunes (R., Calif.) proposed withholding federal aid to government entities that don’t accurately report pension funding. That would be a step forward but would not solve the problem of underfunding.

I obviously agree that there should be no bailouts, but I’m still not convinced that Washington should mandate good policy by state and local governments.

Federalism means the freedom to adopt good policy…but also the leeway to commit fiscal suicide.

Though Andrew Biggs points out that the part about accurate reporting certainly sounds reasonable.

Congress has a tremendous opportunity to require state and local government employee pension plans to accurately disclose their multi-trillion dollar unfunded liabilities. …For years, economists and government agencies like the Congressional Budget Office have called for so-called “fair market valuation,” which both more accurately calculates the value of public pension liabilities and accurately tells those plans that taking more investment risk doesn’t make their plans cheaper. …there’s legislative language already written: Rep. Devin Nunes’s Public Employee Pension Transparency Act (PEPTA), which has a number of Congressional co-sponsors including House Speaker Paul Ryan, would require state and local plans to accurately disclose their liabilities using fair market valuation. The federal government would respect state and local rights by not forcing any changes to how pensions are funded, but Nunes’s plan would require that state and local governments to tell the public – including people thinking of purchasing municipal bonds – how much they really owe to their pensions.

P.S. By the way, advocates of limited government don’t experience many victories, but there actually was a very good reform of the pension system for federal bureaucrats during the Reagan years. Yes, federal bureaucrats are still over-compensated, but it’s not nearly as bad as it used to be. Yet another example of how Reaganomics was a success.

P.P.S. Shifting to bad news (or laughable news), the hacks in California tried to argue that lavish pensions for bureaucrats boost the economy. Andrew Biggs does a great job of debunking this nonsense.

The California Public Employee Retirement System (CalPERS) issued a report in July claiming that its benefit payments to retired government employees in 2013-2014 “supported 104,974 jobs throughout California and generated more than $15.6 billion in additional economic output.” …To reduce pension benefits for public employees, the study implies, would harm the overall California economy. …This study is nothing short of propaganda that wouldn’t get a passing grade in a freshman economics course. …the CalPERS study lacks one important component, called “counting both sides of the equation.” It needs to count economic costs as well as economic benefits. …CalPERS doesn’t create money out of thin air. Every single dollar of CalPERS benefits comes from a dollar that taxpayers or government employees contributed to the program or from the interest earned on those contributions.

Sounds like the bureaucrats at CalPERS should be working for the Congressional Budget Office.

P.P.P.S. The focus of this column is on the inherent instability of defined-benefit pension plans for bureaucrats, but let’s not lose sight of the fact that the underlying issue is that bureaucrats are ripping off taxpayers. Here are some blurbs from aReason report by Eric Boehm on how this scam works in California.

If public service truly is a sacrifice, then join me in shedding a tear for the 20,900 public workers in California who pulled down more than $100,000 in retirement benefits during 2015. …Leading the way for 2015 was Michael Johnson. The former Solano County administrator received a $388,407 pension last year. …Rounding out the top three are Stephen Maguin, a former Los Angeles County Sanitation District general manager who pulled down $340,811 in 2015 and Joaquin Fuster, a former UCLA professor who got a pension worth $338,412 last year. …Curtis Bowden, a former member of the California Highway Patrol…retired all the way back in 1947, which means he’s been collecting pension checks for 68 years, after working just 5.3 years for the state. He got $24,800 from CalPERS in 2015.

Wow, I’m not sure what’s more impressive, Getting an annual pension of nearly $400K after being a country bureaucrat or working for just a bit over five years and getting 68 years worth of retirement checks?

Seems like both of them should be part of the Bureaucrat Hall of Fame.