Donald Trump is, to be charitable, a rather unique and colorful presidential candidate. He seems incapable of letting a day pass without doing something that makes the political establishment shudder with disdain.

Since I’m not a fan of the status quo in Washington, I have no objection to ruffling the feathers of DC insiders. That being said, it’s important to look at why Trump elicits such hostility.

- Is he upsetting the establishment because he intends to cut back on thepervasive nest-feathering and lucrative cronyism of Washington?

- Or is he upsetting the establishment simply by, well, being a jerk?

The bottom line is that the enemy of your enemy isn’t always your friend.

In other words, my ideal candidate almost surely would be hated by the crowd in DC, but the hostility would be based on the candidate’s agenda to shrink the size and scope of the federal government, not because the candidate makes offensive and/or controversial statements.

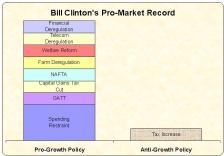

Heck, I’d be willing to forgive a certain amount of distasteful behavior in a politician if that was the price of getting a genuine reformer. For what it’s worth, I’m even willing to tolerate a politician’s misbehavior if he simply allows good reform to happen, which is why I now have a certain after-the-fact fondness for Bill Clinton’s presidency.

if that was the price of getting a genuine reformer. For what it’s worth, I’m even willing to tolerate a politician’s misbehavior if he simply allows good reform to happen, which is why I now have a certain after-the-fact fondness for Bill Clinton’s presidency.

As a policy wonk, I don’t spend much time wondering whether Trump is a good or stable person. I’m more focused on the policies he would push (or simply allow) if he wound up in the White House.

On that basis, I’m not brimming with optimism. Here’s some of what I wrote for the U.K.-based Guardian, when asked to share my assessment about the possible economic policy agenda of a Trump Administration. I start by saying we are in uncharted territory.

Normal presidential candidates put forth proposals that usually have been vetted by policy experts. They also generally have track records from their time as elected officials. …Trump is not a normal candidate.

I then point out that Trump is all over the map on policy.

…his views on major economic issues are eclectic. He promises a big tax cut, but it’s probably not very serious since he has no concomitant plan to restrain the growth of government spending. He threatens to impose steep tariffs, which would risk triggering a trade war, but he claims protectionism would merely be a stick to extort concessions from trading partners. ….He makes noises about potentially defaulting on debt but then pivots and says the debt can be financed by printing money. …either approach causes angst among most economists.

My conclusion (which is nothing more than a guess) is that the overall burden of government would increase with Trump in the White House.

With all this uncertainty about what Trump really believes, it’s impossible to guess which policies will change and how the economy would be impacted. For what it’s worth, libertarians generally fear that Trump ultimately would govern as a left-leaning populist.

By the way, this is also why I was not a fan of Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain, or Mitt Romney.

Simply stated, non-ideological Republicans (whether pseudo-populists like Trump or career politicians) don’t challenge the conventional wisdom of Washington. And that generally results in a go-along-to-get-along approach to policy, which means continued growth of government.

Which is why I’ve pointed out that Democrats in the White House sometimes result in less damage.

By the way, my jaundiced assessment of Trump does not imply that Hillary Clinton is any better. She also has personal foibles that – in a normal society – would disqualify her from holding public office.

And I also wrote for the Guardian about her approach to economic policy, which is basically the same direction as Bernie Sanders but at a slower pace.

…she would move public policy incrementally to the left. Some tax increases, but not giant tax increases. Some new regulations, but not complete government takeovers of industry. A bigger burden of government spending, but not turning America into Greece. An increase in the minimum wage, but not up to $15 an hour. More subsidies for higher education, but not an entitlement for everyone. And some restrictions on trade, but no sweeping reversal of the pro-trade consensus that has existed since the second world war.

In other words, become Greece at 55 miles per hour rather than Bernie’s desire to become Greece at 90 miles per hour.

———

Image credit: Gage Skidmore | CC BY-SA 2.0.