America’s main long-run retirement challenge is our pay-as-you-go Social Security system, which was created back when everyone assumed we would always have a “population pyramid,” meaning relatively few retirees and lots of workers.

But as longevity has increased and fertility has decreased, the population pyramid increasingly looks like a cylinder. This helps to explain why the inflation-adjusted shortfall for Social Security is now about $37 trillion (and if you include the long-run shortfalls for Medicare and Medicaid, the outlook is even worse).

But as longevity has increased and fertility has decreased, the population pyramid increasingly looks like a cylinder. This helps to explain why the inflation-adjusted shortfall for Social Security is now about $37 trillion (and if you include the long-run shortfalls for Medicare and Medicaid, the outlook is even worse).

But Social Security is not the only government-created retirement problem. State and local governments have “defined benefit” pension systems for their bureaucrats, which means that their bureaucrats, when they retire (often at an early age), are entitled to receive monthly checks for the rest of their lives based on formulas devised by each state (based on factors such as years employed in the bureaucracy, pay levels, contributions, etc).

Unlike Social Security (which has a make-believe Trust Fund), these pension systems are supposed to be “funded” in the proper sense, which means that money supposedly is set aside and invested every year so that there will be a big nest egg that can be used to pay benefits to future retirees.

At least that’s how it’s supposed to work in theory. In reality, politicians like promising big retirement benefits to government bureaucrats, but they oftentimes aren’t willing to actually set aside the money needed to fund the nest egg. After all, it’s more fun to spend the money appeasing other interest groups (state and local bureaucrats don’t approve of underfunding, but their retirement benefits generally are seen as a contractual obligation, so they don’t have much incentive to lobby for honest accounting).

The net result is that every retirement system for state government workers is underfunded. How far in the red? That’s a hard question to answer because you have to make long-run assumptions about the investment earnings of the various pension funds.

But the answer is going to be a big number regardless of methodology. According to a new report from the American Legislative Exchange Council, the shortfall is enormous.

When state pension funds are examined through the lens of a more realistic valuation, pension funding gaps are revealed to be much larger than reported in official state financial documents. This report totals state-administered plans’ assets and liabilities and finds nationwide total unfunded liabilities to be $5.59 trillion. The nationwide funding level is a mere 35 percent, which is one percentage point lower than two years ago. Combined across all states, the price tag for unfunded pension liabilities is now $17,427 for every man, woman and child in the United States. …Taxpayers are on the hook for the legal obligation to cover the promised benefits of traditional, defined-benefit pension plans. …When unfunded pension liabilities are viewed as shared debt placed on each individual, Alaska, where each resident is on the hook for a staggering $42,950, tops the list. Ohio and Illinois follow for the highest per person unfunded pension liabilities.

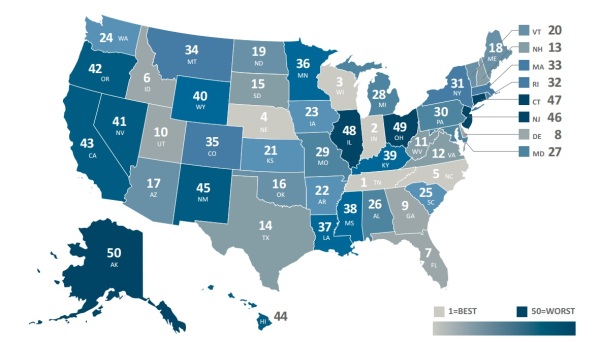

Here’s a map from the report. It’s bad news if your state is dark blue. And if your state is gray, your burden is relatively low.

Though keep in mind that these numbers are not adjusted for state income.

Louisiana, Mississippi, and Kentucky get bad scores, but they probably are in even deeper trouble that lower-ranked states like California and New Jersey where per-capita income is higher (yes, the cost of living is lower in those southern states, but that doesn’t matter since the relevant comparison is per-capita income vs per-capita pension liabilities.

but they probably are in even deeper trouble that lower-ranked states like California and New Jersey where per-capita income is higher (yes, the cost of living is lower in those southern states, but that doesn’t matter since the relevant comparison is per-capita income vs per-capita pension liabilities.

The ALEC report is more pessimistic than other estimates, but that’s because they use more cautious assumptions about the potential investment earnings of the various pension funds that manage money for state and local bureaucrats.

State Budget Solutions uses a more reasonable valuation to determine the unfunded liabilities of public pension plans. Given that many plans’ assumed rates of return are too high and invite risk, State Budget Solutions uses a more prudent rate of return, rather than the loftiest goals of money managers. This study uses a rate of return based on the equivalent of a hypothetical 15-year U.S. Treasury bond yield. …. State Budget Solutions is not alone in calling attention to the flawed accounting practices of state agencies. A recent study released by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, Pension Debt: United States Public Employee Pension Systems, also suggests that states use unrealistically high rates of return to discount their pension liabilities. The study found that pension debt totals $4.8 trillion, a finding similar to this report.

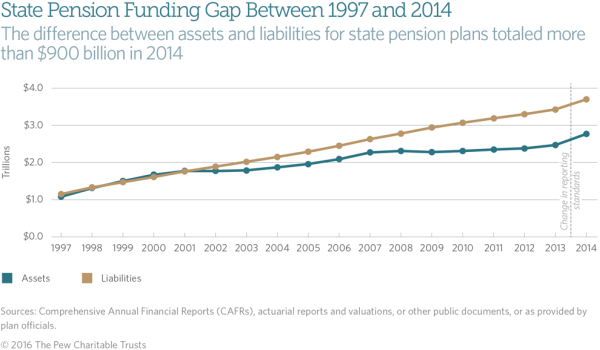

A new study from Pew isn’t nearly as pessimistic, but it still shows a huge gap.

The nation’s state-run retirement systems had a $934 billion gap in fiscal year 2014 between the pension benefits that governments have promised their workers and the funding available to meet those obligations. …This brief focuses on the most recent comprehensive data from all 50 states and does not reflect the impact of weaker investment performance in fiscal 2015, which averaged 3 percent. Performance has been even weaker in the first three quarters of fiscal 2016. …Total pension debt is expected to be over $1 trillion for state plans, an increase of more than 10 percent from fiscal 2014. When combined with the shortfalls in local pension systems, this estimate reaches more than $1.5 trillion for fiscal 2015 and will likely remain close to historically high levels as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

Here’s a visual from the report showing how the fiscal outlook for state pension systems has deteriorated over the past 15-plus years.

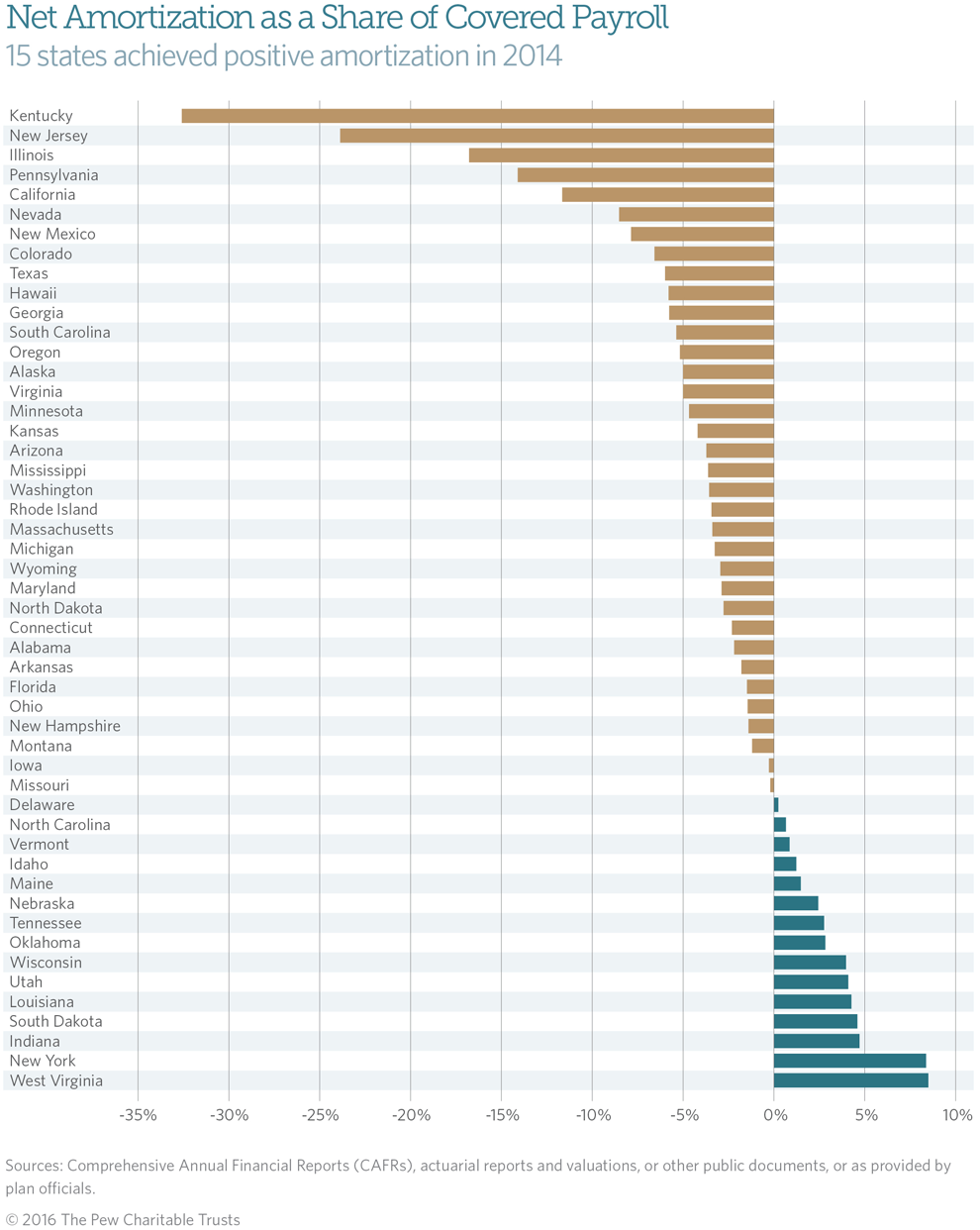

Equally troubling, most states are heading in the wrong direction.

…this brief shows that 15 states currently follow policies that meet the positive amortization benchmark—exceeding 100 percent of needed funding—and can be expected to reduce pension debt in the near term. The remaining 35 states fell short; those performing the worst on this measure typically had the largest unfunded pension liabilities.

Here’s the chart from the study. As you can see, Kentucky, New Jersey, and Illinois are falling deeper into the red at the fastest rate.

Kudos to New York and West Virginia, by the way, for being the most aggressive in trying to address long-run problems.

Moody’s Investor Services also has a new report on pension shortfalls. Here are some of the highlights, or perhaps lowlights would be a more appropriate word.

Total US state aggregate adjusted net pension liabilities (ANPL) totaled $1.25 trillion, or 119% of revenue in fiscal 2015, Moody’s Investors Service says in a new report. The results, based on compliance with new GASB 68 accounting rules, set a new ANPL baseline and are poised to rise for the next two fiscal years as market returns fall below annual targets. “The median return for public pension plans in FY 2016 was 0.52% compared to an average assumed investment return of 7.5%,” Moody’s Vice President — Senior Credit Officer Marcia Van Wagner says. “We project that aggregate state ANPL will grow to $1.75 trillion in FY 2017 audits.” Moody’s new report also introduces a new “Tread Water” benchmark, which measures whether states’ annual contributions to their pensions are enough to keep the unfunded net liability from growing. …there were several states whose pension contributions were notably below the Tread Water mark, including Kentucky (Aa2 stable), New Jersey (A2 negative), Illinois (Baa2 negative), and Texas (Aaa stable). …The states with the highest pension burdens — measured as the largest three-year average ANPL as a percent of state governmental revenue — were consistent with previous years. Illinois topped the list with pension liabilities at 280% of total governmental revenue, followed by Connecticut (Aa3 negative) at 209%, Alaska (Aa2 negative) at 179%, Kentucky at 162%, and New Jersey at 157%.

Wow! It doesn’t matter what report you look at, or what methodology is being used: Illinois, New Jersey, and Kentucky are a big mess (Alaska’s numbers also are awful, but the state – within certain limits – can use energy tax revenues to cover much of its shortfall).

So what’s the solution to all this mess? As I noted a couple of months ago when sharing other grim numbers about state pension systems, the answer is to, 1) stop promising excessive benefits to bureaucrats (and stop giving them excessive pay as well), and 2) switch to “defined contribution” plans so that workers have their own piles of money and the underfunding problem automatically disappears.