If you asked a bunch of Republican politicians for their favorite fiscal policy goals, a balanced budget amendment almost certainly would be high on their list.

This is very unfortunate. Not because a balanced budget amendment is bad, per se, but mostly because it is irrelevant. There’s very little evidence that it produces good policy.

Before branding me as an apologist for big government or some sort of fiscal heretic, consider the fact that balanced budget requirements haven’t prevented states like California, Illinois, Connecticut, and New York from adopting bad policy.

Or look at France, Italy, Greece, and other EU nations that are fiscal basket cases even though there are “Maastricht rules” that basically are akin to balanced budget requirements (though the target is a deficit of 3 percent of economic output rather than zero percent of GDP).

Indeed, it’s possible that balanced budget rules contribute to bad policy since politicians can argue that they are obligated to raise taxes.

Consider what’s happening right now in Spain, as reported by Bloomberg.

Spain’s acting government targeted an extra 6 billion euros ($6.7 billion) a year from corporate tax as it tried to persuade the European Commission not to levy its first-ever fine for persistent budget breaches. …Spain is negotiating with the European Commission over a new timetable for deficit reduction, as well as trying to sidestep sanctions after missing its target for a fourth straight year. Spain is proposing to bring its budget shortfall below the European Union’s 3 percent limit in 2017 instead of this year, Guindos said.

Wow, think about what this means. Spain’s economy is very weak, yet the foolish politicians are going to impose a big tax hike on business because of anti-deficit rules.

This is why it’s far better to have spending caps so that government grows slower than the private sector. A rule that limits the annual growth of government spending is both understandable and enforceable. And such a rule directly deals with the preeminent fiscal policy problem of excessive government.

Which is why we’ve seen very good results in jurisdictions such as Switzerland and Hong Kong that have such policies.

The evidence is so strong for spending caps that even left-leaning international bureaucracies have admitted their efficacy.

I’ve already highlighted how the International Monetary Fund (twice!), theEuropean Central Bank, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have acknowledged that spending caps are the most, if not only, effective fiscal rule.

Here are some highlights from another study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

…the adoption of a budget balance rule complemented by an expenditure rule could suit most countries well. As shown in Table 7, the combination of the two rules responds to the two objectives. A budget balance rule encourages hitting the debt target. And, well-designed expenditure rules appear decisive in ensuring the effectiveness of a budget balance rule (Guichard et al., 2007). Carnot (2014) shows also that a binding spending rule can promote fiscal discipline while allowing for stabilisation policies. …Spending rules entail no trade-off between minimising recession risks and minimising debt uncertainties. They can boost potential growth and hence reduce the recession risk without any adverse effect on debt. Indeed, estimations show that public spending restraint is associated with higher potential growth (Fall and Fournier, 2015).

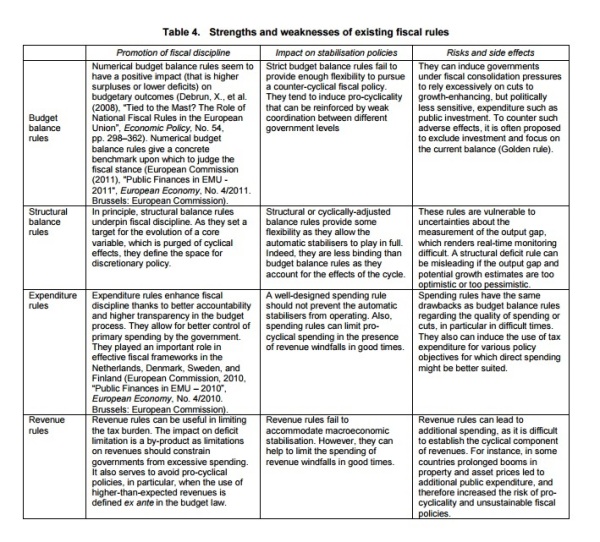

Here’s a very useful table from the report.

As you can see, expenditure rules have the most upside and the least downside.

Though it’s important to make sure a spending cap is properly designed.

Here are some of the key conclusions on Tax and Expenditure Limitations (TELs) from a study by Matt Mitchell (no relation) and Olivia Gonzalez of the Mercatus Center.

The effectiveness of TELs varies greatly depending on their design. Effective TEL formulas limit spending to the sum of inflation plus population growth. This type of formula is associated with statistically significantly less spending. TELs tend to be more effective when they require a supermajority vote to be overridden, are constitutionally codified, and automatically refund surpluses. These rules are also more effective when they limit spending rather than revenue and when they prohibit unfunded mandates on local government. Having one or more of these characteristics tends to lead to less spending. Ineffective TELs are unfortunately the most common variety. TELs that tie state spending growth to growth in private income are associated with more spending in high-income states.

In other words, assuming the goal is better fiscal policy, a spending cap should be designed so that government grows slower than the productive sector of the economy. That’s music to my ears.

And the message is resonating with many other people in Washington who care about good fiscal policy.