Last year, I explained the theoretical argument against antitrust laws, pointing out that monopoly power generally exists only when government intervenes.

- There’s monopoly power when government takes over a sector of the economy (i.e., air traffic control, Postal Service, Social Security, etc).

- There’s monopoly power when government prohibits or restricts competition in a sector of the economy (cable TV franchises, occupational licensing, etc).

- There’s monopoly power when government subsidizes select participants in a sector of the economy (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, etc).

Now it’s time to consider a real-world example from the private sector and ask whether we should be concerned about monopoly power. AT&T and Time Warner have announced a merger, a step that has triggered lots of hand-wringing by politicians.

But as I explain in this interview for a British news outlet, the expanded company won’t have any power or ability to coerce me, particularly so long as politicians don’t create any “barriers to entry” to hinder the entry of new competitors to the market.

The Skype connection became garbled for a few seconds at the end of the interview, but I think my point about the misuse of antitrust laws was reasonably clear.

Suffice to say that allowing politicians and bureaucrats to have any authority over mergers is a recipe for abuse and corruption as companies try to use antitrust laws to sabotage their competitors.

Let’s see what some experts have written on this topic. And we’ll start by looking at the big picture. Writing for Bloomberg, Professor Tyler Cowen points out that antitrust laws often don’t make sense.

Reading through old cases does not induce great faith in the contemporary usefulness of 19th- and 20th-century antitrust laws. …For instance, the famous suits against Standard Oil, Kodak and Alcoa wouldn’t make sense in today’s globalized economy. …In 1998, the U.S. Justice Department initiated an antitrust suit against Microsoft, partly on the grounds that the company sought to extend its market power to browsers. Few people today think the company’s Internet Explorer browser failed because the government restored competitiveness; Firefox and Google built better software. Yet prosecutors spent years distracting the talent of one of America’s most successful companies, as they had with IBM earlier in a 13-year case dropped in 1982.

And he points out how monopoly power often is created by government intervention and regulation.

…there is a strong case that growing concentration in the hospital market has raised health-care costs. Some major metropolitan areas have only a small number of hospital chains. Part of the problem is that highly regulated environments encourage consolidation and larger firms to deal with compliance costs… Cable television is another area where anti-monopoly remedies might be appropriate, but keep in mind that cable is typically a government-created local monopoly.

Now let’s look at the specific case of the AT&T/Time Warner merger.

Holman Jenkins of the Wall Street Journal is not impressed by those who want government interference. And he shares my disdain for the way influence peddlers in Washington are the big beneficiaries of antitrust laws.

…this week’s proposed merger of AT&T and Time Warner is eliciting opposition that is ferocious, idiotic and almost contentless. …tens of thousands of people in Washington make their living by extracting rents from companies going about their business and trying to adapt to besetting waves of technological and market change. …Unwisely, Silicon Valley mostly sat out 2014’s epic battle over the Obama administration’s desire to impose antique utility regulation on broadband. Its argument: Who cares? Technology will swamp the regulators with broadband ubiquity anyway, so why pick a fight…the Valley’s naïfs may discover they have underestimated the power of bureaucratic perversity and political indifference to things that would actually serve the public good. One way to look at the inevitable torture AT&T is about to undergo at the hands of Washington’s regulators: It will be the first test of the libertarian-optimist theory that technology is more powerful than a bloody-minded bureaucrat.

Last but not least, Paula Dwyer’s Bloomberg column takes a dim view of those who want the heavy foot of government to second guess the invisible hand of the market.

Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, wearing their populist stripes, want regulators to block it outright. …the politicians’ concerns are overblown. …Antitrust, of course, is meant to protect consumers from the higher prices and reduced choices that result when a company has market power. But a merged AT&T and Time Warner are in different industries, and their merger wouldn’t affect ownership concentration. Nor would it result in the loss of a competitor from the market.

And she points out the dismal history of antitrust enforcement.

…think back to 1974 to the original AT&T antitrust case, which also began from a fear of vertical integration. …For sure, AT&T had a monopoly, but it was created and sanctioned by the federal government. All that was needed was a government deregulation order and a green light that it wouldn’t block competitors. Instead, the U.S. sued to break up Ma Bell. …If the U.S. had simply deregulated plain old telephone service, any one of these technologies could have forced AT&T to adjust or disappear. The U.S.’s 1998 antitrust case against Microsoft had much the same fighting-the-last-war problem. …while the Justice Department was fixating on browsers and operating systems, the personal computer was losing market share to laptops, which lost out to tablets and which are now being overtaken by smartphones. While Microsoft was bogged down with the Windows case, which it eventually settled in 2001 on favorable terms to the company, a new generation of tech giants — Google, Facebook, Amazon — took flight. The lesson is that a technology or media conglomerate’s dominance these days is almost certainly transitory.

In other words, let the merger proceed. It may be a wise business decision. Or it may be a foolish business decision.

But that outcome should be determined by the preferences of consumers in a competitive marketplace.

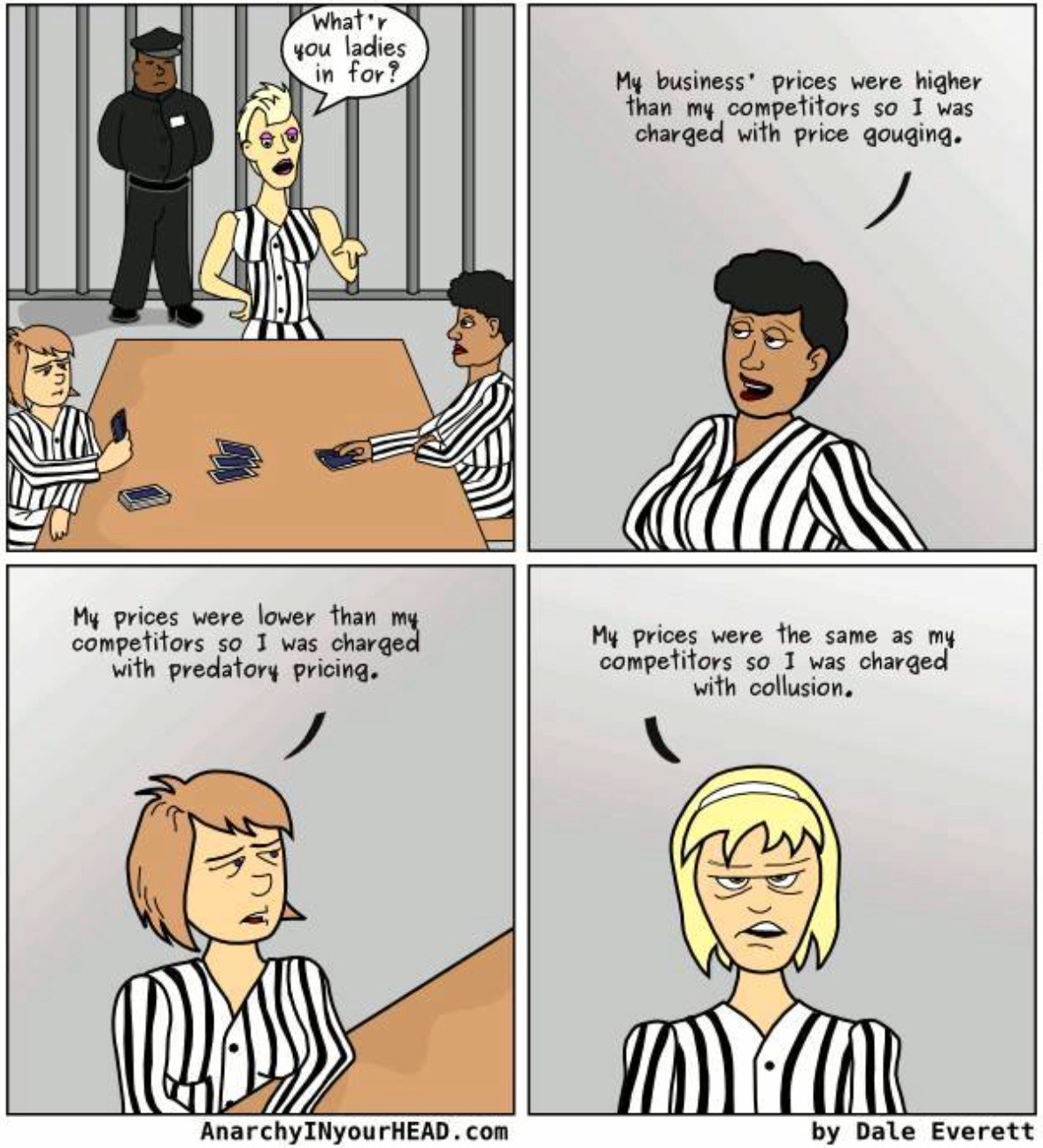

The heavy foot of government shouldn’t play a role. Especially since, as noted by this cartoon, antitrust laws are so broad and vague that companies can get in legal trouble for charging more than their competitors, less than their competitors, and the same as their competitors.

P.S. If this information hasn’t been sufficient to make you skeptical about antitrust laws, then also keep in mind that the European Commission’s tax shakedown of Apple is based on antitrust policy rather than tax policy.