If nothing else, Belgian politicians deserve credit for perseverance. One year ago, the nation was considering a “tax shift” that would reduce taxes on labor and increase taxes on consumption.

I pointed out that this didn’t make much sense since it wouldn’t alter the wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. In other words, the government might not take as much when you earned your income, but it would compensate by taking more when you consumed your income, so there would be no improvement in your living standards and therefore no incentive to be more productive and earn more money.

I pointed out that this didn’t make much sense since it wouldn’t alter the wedge between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption. In other words, the government might not take as much when you earned your income, but it would compensate by taking more when you consumed your income, so there would be no improvement in your living standards and therefore no incentive to be more productive and earn more money.

Now the government in Belgium is considering a different “tax shift.” Here are some excerpts from a report in the Financial Times.

The Belgian government is rolling out a “tax shift” policy that Charles Michel, the country’s 40 year-old prime minister, says is aimed…to support people on low to medium incomes by reducing the taxes and social security charges on labour — some of the highest in Europe — and to make up the shortfall by boosting taxes on capital.

I’m underwhelmed by this approach.

Though let’s start with what’s good. The government should be lowering taxes on work. As the article notes, employees in Belgium are treated worse than medieval serfs, who only had to surrender one-third of their output to the Lord of the Manor.

…according to 2015 OECD data, is that an unmarried Belgian worker without children faced the highest “tax wedge” as a proportion of income of any citizen in the 35-country club. It stood at 55.3 per cent, compared with an average of 35.9 per cent. The burden results from a combination of high social security charges and a 50 per cent tax rate kicking in at a relatively low level — around €38,000.

Here’s one of the charts from the article. As you can see, greedy politicians get the lion’s share of the money when a Belgian worker chooses to earn income.

At the risk of understatement, the overall tax burden in Belgium is stifling.

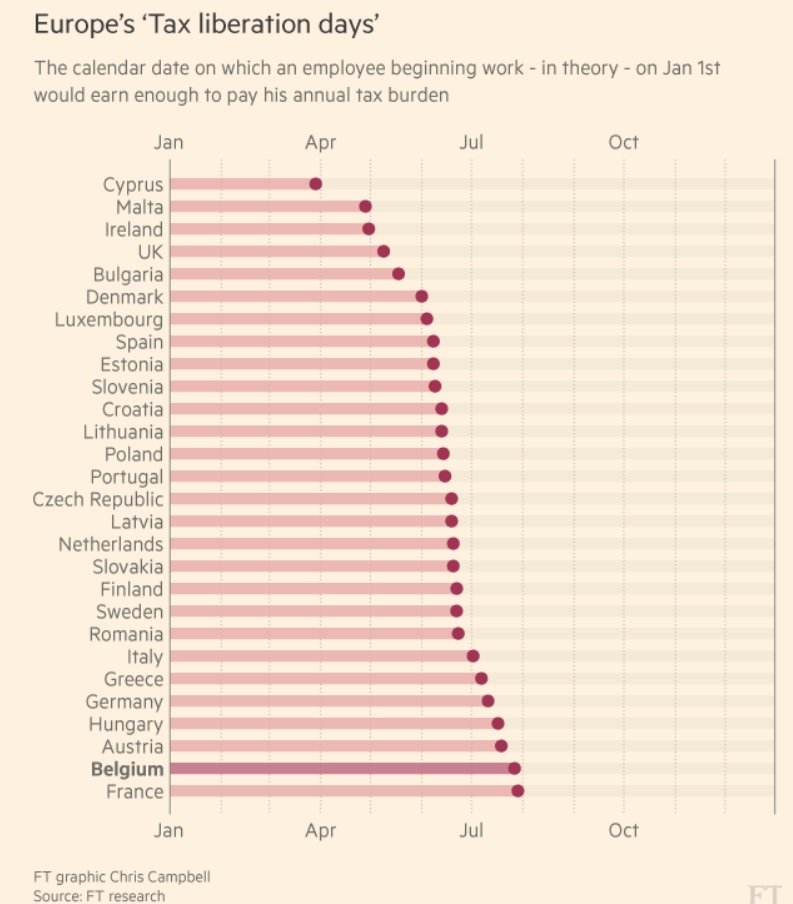

Here’s another chart, this one showing how long European workers must toil before satisfying the tax demands of their governments.

I don’t know if the methodology is similar to the Tax Freedom Day calculations for the United States, and it’s unclear whether this is just a measure of the tax burden on labor income, or whether it also captures other taxes that workers pay (corporate income tax, value-added tax, excise taxes, etc). But it’s clear than Belgian workers have a terrible system.

Now for the bad news. Belgian politicians want to cut taxes on workers, but they say they want to compensate by imposing higher taxes on saving and investment.

That’s not a good idea since the productivity – and therefore compensation – of workers is very much linked to the amount of machinery, tools, and technology that’s available. So when politicians increase the tax burden on saving and investment, that reduces an economy’s stock of capital, and workers wind up with less pre-tax income than they would have earned otherwise.

That’s not a good idea since the productivity – and therefore compensation – of workers is very much linked to the amount of machinery, tools, and technology that’s available. So when politicians increase the tax burden on saving and investment, that reduces an economy’s stock of capital, and workers wind up with less pre-tax income than they would have earned otherwise.

Let’s see what Belgium’s government is trying to achieve. Here’s another blurb from the article.

Some changes, including a new financial speculation tax, were driven through last year and there are more to come. One of Mr Michel’s coalition partners, the Flemish Christian Democrats, is even pushing for a French-style wealth tax. …The speculation tax is estimated to bring in only about €20m this year, considerably less than the €34m initially predicted by the government. Also, there is little support for a more comprehensive inheritance tax. To Michel Maus, a tax law professor at Brussels Free University, the government’s efforts so far to increase taxation of capital amount to “window dressing” and “a bit political propaganda”.

I suppose the relative dearth of specific tax hikes on saving and investment is the good news inside the bad news.

Indeed, while the government did impose a tax on “speculation” (and discovered a Laffer Curve-effect when revenues came in below projections), there actually are some proposals to reduce the tax burden on saving and investment. For instance, the government has announced a move to lower the nation’s 33.99 percent corporate tax rate.

Under Minister Van Overtveldt’s current plan, the corporate tax rate would be reduced to 28% in 2017, 24% in 2018 and 20% in 2020, and would ultimately apply to companies of all sizes. At 20%, Belgium’s corporate tax rate would fall just below the EU average and would place the country in a more competitive – but not a leading – position within its peer group. …In addition, the Finance Minister is considering abolishing the Fairness Tax as well as the minimum tax on capital gains on shares, as advocated by the Chamber. The plan also includes a full tax deduction on qualifying dividends received from subsidiaries, as is the case in the Netherlands and Luxembourg, in lieu of the current deduction of 95%.

There are some offsetting tax hikes in this new plan, so this proposal presumably isn’t as good as it sounds, but it’s hard to argue with an initiative that drops the corporate rate by almost 14 percentage points.

So while I don’t like the theoretical concept of a tax shift from labor to capital, the net effect of all the tax changes in Belgium may be positive for the simple reason that the anti-growth part of the shift isn’t happening.

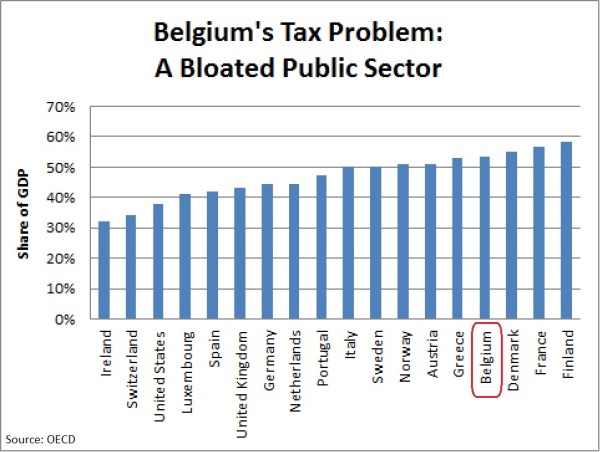

But regardless of what eventually happens, it is unlikely that Belgium will make much long-run progress because the country is burdened by one of the largest public sectors in the world.

Here some data from the OECD on the burden of government spending in Western Europe (and the United States). As you can see, Belgium isn’t as bad as France, but it’s worse than Greece, Sweden, and Italy.

The bottom line is that you can’t have a non-punitive tax system when government is consuming half of what the private sector produces.

So I think I’m semi-happy with what Belgian politicians are doing in the short run (reserving the right to change my mind as more details are unveiled), but I don’t have much long-term hope in the absence of effective reforms to shrink the burden of government spending.

But hope springs eternal. Maybe the government will adopt a Swiss-style spending cap.

P.S. Here’s a story that tells you everything you need to know about Belgium’s bloated public sector.

P.P.S. And if you look at America’s long-run fiscal projections, the problems in Belgium today will be problems in the United States in the not-too-distant future.