It’s very hard to be optimistic about Japan. I’ve even referred to the country as a basket case.

But my concern is not that the country has been mired in stagnation for the past 25 years. Instead, I’m much more worried about the future. The main problem is that Japan has the usual misguided entitlement programs that are found in most developed nations, but has far-worse-than-usual demographics. That’s not a good long-term combination.

As I repeatedly point out in my speeches and elsewhere, a modest-sized welfare state can be sustained in a nation with a population pyramid. But even a small welfare state is a challenge for a country with a population cylinder. And it’s a crisis for a jurisdiction such as Japan that will soon have an upside-down pyramid.

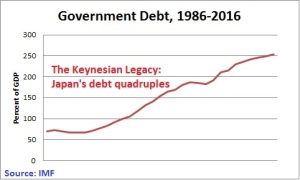

To make matters worse, Japanese politicians don’t seem overly interested in genuine entitlement reform. Instead, most of the discussion (egged on by the tax-free bureaucrats at the OECD) seems focused on how to extract more money from the private sector to finance an ever-growing public sector. But the icing on the cake of bad policy is that Japanese politicians are addicted to Keynesian economics. For two-plus decades, they’ve enacted one “stimulus package” after another. None of these schemes have succeeded. Indeed, the only real effect has been a quadrupling of the debt burden.

But the icing on the cake of bad policy is that Japanese politicians are addicted to Keynesian economics. For two-plus decades, they’ve enacted one “stimulus package” after another. None of these schemes have succeeded. Indeed, the only real effect has been a quadrupling of the debt burden.

The Wall Street Journal shares my pessimism. Here’s some of what was stated in an editorial late last year.

Japan is in recession for the fifth time in seven years, and the…Prime Minister who promised to end his country’s stagnation is failing at the task. …Mr. Abe’s economic plan consisted of three “arrows,” starting with fiscal spending and monetary easing. The result is a national debt set to hit 250% of GDP by the end of the year. The Bank of Japan is buying bonds at a $652 billion annual rate, a more radical quantitative easing than the Federal Reserve’s. …The third arrow, structural economic reform, offered Japan the only hope of sustained economic growth. …But for every step Mr. Abe takes toward reform, one foot remains planted in the political economy of Japan Inc. In April 2014, Mr. Abe acquiesced to a disastrous three percentage-point increase in the value-added tax, to 8%, pushing Japan into its first recession on his watch. More recently, he has pushed politically popular but economically ineffectual spending measures on child care and help for the elderly. …only 25% of the population now believes Abenomics will improve the economy. Reality has a way of catching up with political promises.

You might think that even politicians might learn after repeated failure that big government is not a recipe for prosperity.

But you would be wrong.

Notwithstanding the fact that Keynesian economics hasn’t worked, Japanese politicians are doubling down on the wrong approach.

According to a report from Bloomberg, American Keynesians (when they’re notbusing giving bad advice to Greece) are telling Japan to dig a deeper hole.

Paul Krugman urged Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to…expand fiscal stimulus to revive the economy.

Reuters filed a similar report.

U.S. economist Paul Krugman said on Tuesday he advised Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to…boost fiscal spending… Krugman’s advice was the same as that which fellow U.S. economist Joseph Stiglitz gave Abe last week.

Indeed, there apparently was a consensus for bigger government.

Every one of the economists that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has invited here for a series of meetings with policymakers has recommended that Japan let loose government spending… When Abe asked why consumer spending has remained feeble since the 2014 consumption tax increase, the U.S. academic suggested the answer lies in expectations that fiscal stimulus will end. …Abe’s government…appears to be seeking to rally the G-7 for aggressive fiscal policy.

So why did the Japanese government create an echo chamber of Keynesianism?

Perhaps because politicians want an excuse to buy votes with other people’s money.

With an upper house election looming in July, ruling coalition lawmakers also are eager to dole out massive public spending.

And it appears that Japanese politicians are happy to take advice when it’s based on their spending vice ostensibly being a fiscal virtue.

That’s not too shocking, but the Keynesian scheme that’s being prepared is a parody even by Krugmanesque standards.

Japan’s government is considering handing out gift certificates to low-income young people in a supplementary budget for fiscal 2016 as consumer spending remains sluggish on a slow wage recovery, the Sankei Shimbun newspaper reported Thursday. Government officials believe certificates for purchasing daily necessities would lead to spending, unlike cash handouts which could be saved… The additional fiscal program would follow a similar measure for seniors and the ruling coalition would use it to gain voter support before the Upper House election expected in July, the daily said.

Maybe the politicians will succeed in buying votes, but they shouldn’t expect better economic performance. Giving people gift certificates won’t alter incentives to work, save, and invest (the behaviors that actually result in more economic output).

Indeed, on the margin these handouts may lure a few additional people out of the labor force.

The plan is foolish even from a Keynesian perspective. Since money is fungible, do these people really think gift certificates will encourage more spending that cash handouts?

By the way, another reason to be pessimistic about Japan is that there apparently aren’t any politicians who understand economics. Or at least there aren’t any that want good policy. The opposition party isn’t opposed to Keynesian foolishness. Instead, it’s leader is only concerned about who gets the goodies.

Katsuya Okada, the leader of the main opposition Democratic Party of Japan, said in parliamentary debate in January. “Elderly people are not the only ones who are suffering. Among the working generation, only a limited number of people are feeling the fruit of Abenomics.”

The bottom line is that Japan will become another Greece at some point. I’m not smart enough to know whether that will happen in five years or twenty-five years, but barring a radical reversal in government policy, the nation is in deep long-run trouble.

———

Image credit: victorpalmer | Pixabay License.