When I tell journalists and politicians that the European fiscal situation is worse today than it was immediately prior to the crisis, they don’t believe me. What about all the spending cuts, they ask? What about the draconian austerity? And the Troika-imposed fiscal restraint?

I tell them it’s mostly been a mirage. It turns out that “austerity” in Europe is simply another way of saying massive tax increases. National governments have boosted tax burdens substantially, but there hasn’t been much spending restraint.

I tell them it’s mostly been a mirage. It turns out that “austerity” in Europe is simply another way of saying massive tax increases. National governments have boosted tax burdens substantially, but there hasn’t been much spending restraint.

This is a topic I spoke about yesterday at a conference in Prague, which was hosted by the European Conservatives and Reformers bloc of the European Parliament.

My panel’s topic was “Current Challenges to the Transatlantic Partnership” and I focused on economic stagnation and fiscal crisis.

Regarding economic stagnation, I pointed out that there’s very little growth in Europe and substandard growth in the United States.

Regarding economic stagnation, I pointed out that there’s very little growth in Europe and substandard growth in the United States.

By itself, that’s a problem but not a crisis.

The crisis (or at least what I argue is a looming crisis) is that Europe’s fiscal situation is worse today than it was when last decade’s fiscal chaos began.

To put this in concrete terms, I crunched the data for both the “eurozone” nations (those using the common currency) and for the overall European Union.

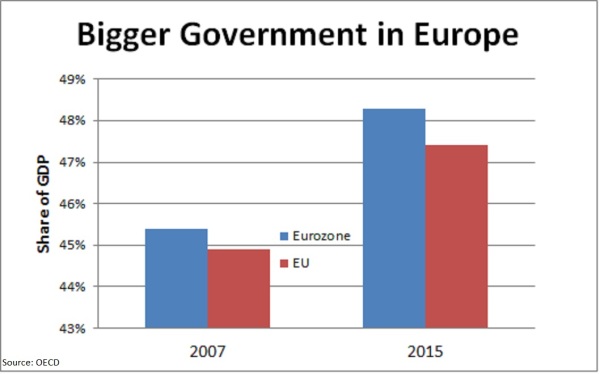

And here are the numbers showing how the burden of government spending has increased in Europe between 2007 and 2015.

At the risk of stating the obvious, there hasn’t been any overall spending restraint on the other side of the Atlantic. This is the chart I will now share with politicians and journalists (as well as anyone else) who is under the illusion that there have been big spending cuts in Europe.

But just as slow growth is a problem rather than a crisis, the same can be said about bigger government. Yes, a larger fiscal burden saps an economy’s vitality and weakens national competitiveness, but it presumably doesn’t by itself produce a crisis.

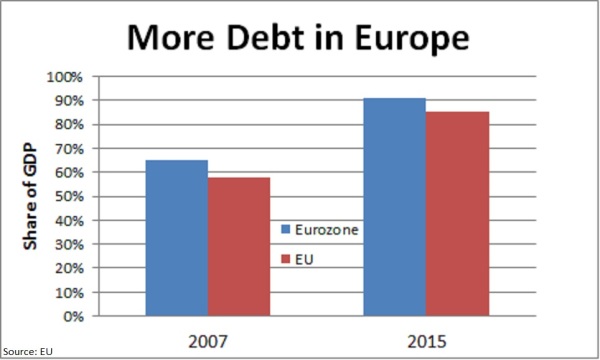

The crisis, at least if last decade is any indication, materializes when investors decide they don’t want to buy a nation’s government debt because they fear they won’t get repaid (i.e., a default). And that happens when a nation’s debt level is perceived to have reached an unsustainable level when compared to the ability of that country’s economy to generate enough output to support that debt.

And I suspect it’s just a matter of time before Europe experiences another such crisis. Here are the numbers, both for euro-using nations as well as the entire European Union, showing that government debt is substantially higher today than it was at the dawn of last decade’s meltdown.

I should point out that there’s no reason why a crisis need occur. If European governments copied Switzerland and put in place some sort of spending cap (a good one that ensures that the burden of government expanded slower than the private sector), then red ink quickly would fall and investors would be much less fearful of a default.

Unfortunately, all the pressure is in the other direction. Indeed, to the limited degree there was any spending restraint after the last crisis, it has largely evaporated.

A story in the New York Times from two years ago illustrates why the mess in Europe is so intractable.

The reporters who authored the story were correct that there was disagreement between Germany and other nations.

…many of the largest European countries are now rebelling against the German gospel of belt-tightening and demanding more radical steps to reverse their slumping fortunes.

But they naively reported that there were genuine cutbacks and they also believed the silly Keynesian argument that smaller government somehow reduces growth.

…eurozone nations buckled under to German demands to slash budget deficits and roll back public services, and then watched in dismay as unemployment rates shot into the double digits and growth collapsed.

In any event, Europe’s self-styled elite decided on a return to the types of bad policy that led to last decade’s fiscal crisis.

Now, France, Italy and the European Central Bank have coalesced into a bloc against Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany, and they are insisting that Berlin change course. …France, which has in modern times been Germany’s indispensable partner in European crisis management, is now in near revolt, and President François Hollande has joined forces with Mr. Renzi, who has presented an expansionary 2015 budget that will cut taxes despite pressure from Brussels to meet deficit targets. Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank, has pressed Germany to temper its insistence on budgetary discipline and to spend more on public works to stimulate the eurozone economy. The French have cheered him on

For what it’s worth, I would have been on Merkel’s side if she was actually pushing for meaningful spending restraint.

But that was not the case. She myopically focused on fiscal balance rather than the size of government, which is bad enough since higher taxes are always the first (and second, and third, …) resort of politicians. But to make matters worse, her motives have always been suspect because of fears that she’s mostly concerned about protecting German banks that foolishly lent a lot of money to profligate governments.

Though that presumably shouldn’t be a major concern today since the European Central Bank is now buying lots of government bonds as part of 1) a foolish experiment in monetary Keynesianism, and 2) an indirect bailout of dodgy governments. Any banks with competent management will have used this opportunity to sell their holdings so the risk of sovereign defaults is borne by the general public.

But let’s set aside speculation on Merkel’s motives. All that really matters is that government in Europe is now bigger and more expensive, with lots of additional red ink. And the European Central Bank is helping to build the house of cards even higher.

This won’t end well, though I very much hope my fears are misplaced.

P.S. Anybody who wants to argue that Europe’s fiscal problems can be solved with higher taxes first needs to explain this set of charts.