There’s a lot of speculation in Washington about what a Trump Administration will do on government spending. Based on his rhetoric it’s hard to know whether he’ll be a big-spending populist or a hard-nosed businessman.

But what if that fight is pointless?

Back in October, Will Wilkinson of the Niskanen Center wrote a very interesting – albeit depressing – article about the potential futility of trying to reduce the size of government. He starts with the observation that government tends to get bigger as nations get richer.

“Wagner’s Law” says that as an economy’s per capita output grows larger over time, government spending consumes a larger share of that output. …Wagner’s Law names a real, observed, robust empirical pattern. …It’s mainly the positive relationship between rising demand for welfare services/transfers and rising GDP per capita that drives Wagner’s Law.

I’ve also written about Wagner’s Law, mostly to debunk the silly leftist interpretation that bigger government causes more wealth (in other words, they get the causality backwards), but also to point out that other policies matter and that some big-government nations have wisely mitigated the harmful economic impact of excessive spending and taxation by having very pro-market policies in areas such as trade and regulation.

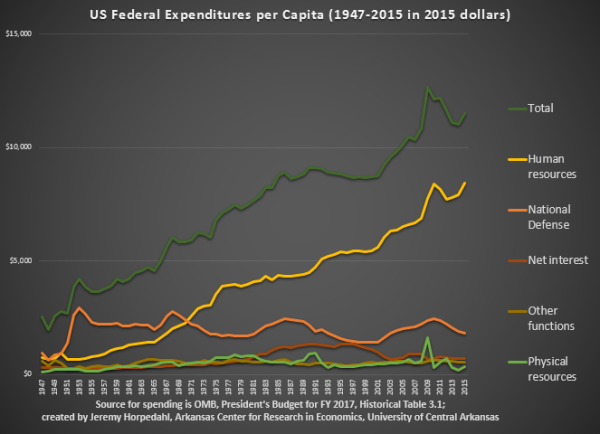

In any event, Will includes a chart showing that there certainly has been a lot more redistribution spending in the United States over the past 70 years, so it certainly is true that the political process has produced results consistent with Wagner’s Law. As America has become richer, voters and politicians have figured out how to redistribute ever-larger amounts of money.

By the way, this data is completely consistent with my recent column that pointed out how defense spending plays only a minor role in America’s fiscal challenge.

But let’s get back to Will’s article. He asserts that Wagner’s Law is bad news for advocates of smaller government.

…free-marketeers tend to insist that the key to achieving higher rates of economic growth is slashing the size of government. After all, it’s true that the private sector is better than government at putting resources to their most productive use and that some public spending crowds out private investment. If you’re really committed to the idea of stronger economic growth through government contraction, you’re pretty much committed to the idea that the pattern behind Wagner’s Law is a sort of fluke—a contingent correlation without any real cause-and-effect basis—and that there’s got to be some workaround or fix.

I don’t particularly agree with his characterization. You can believe (as I surely do) that smaller government would lead to faster growth without having to disbelieve, deny, or debunk Wagner’s Law.

- First, it’s quite possible to have decent growth along with expanding government so long as other policy levers are moving in the right direction. Which is exactly what one Spanish scholar found when examining data for developed nations during the post-World War II period.

- Second, it’s overly simplistic to characterize this debate as government or growth. The real issue is the rate of growth. After all, even France has a bit of growth in an average year. The real issue is whether there could be more growth with a lower level of taxes and spending. In other words, would the rest of the developed world grow faster with Hong Kong-sized government?

All that being said, Will certainly is right in his article when he points out that libertarians and other advocates of smaller government haven’t done a good job of constraining government spending.

He then examines some of the ideas have been proposed by folks on the right who want to constrain spending. Beginning with the starve-the-beast hypothesis.

The idea that it is possible to “starve the beast”—to reduce the size of government by starving the government of tax revenue—springs from this hope. But the actual effect of cutting taxes below the amount necessary to sustain current levels of government spending only underscores the unforgiving lawlikeness of Wagner’s Law. As our namesake Bill Niskanen showed, tax cuts that lead to budget shortfalls don’t lead to corresponding cuts in government spending. On the contrary, financing government spending through debt rather than taxes makes voters feel that government spending is cheaper than it really is, which makes them want even more of it.

Here’s my first substantive disagreement with Will. I’m definitely not in the all-we-have-to-do-is-cut-taxes camp, but I certainly like lower tax rates and I definitely believe that higher taxes would worsen our long-run fiscal outlook.

And I’ve looked closely at the starve-the-beast academic research. Niskanen’s study has some methodological problems and the Romer & Romer study that most people cite when arguing against the starve-the-beast hypothesis actually shows that cutting taxes is somewhat effective so long as tax cuts are durable.

Will then looks at whether it would be effective to end withholding.

…withholding made tax collection cheaper and more reliable. …paying taxes automatically and with a minimum of pain makes it less likely that you’ll be livid about them when you vote. The complaint…is the libertarian/conservative argument against a VAT or national sales tax in a nutshell. It’s the same line of reasoning that leads some libertarians and conservatives to flirt with the idea that we ought to pass a law that requires us to write a single, hugely infuriating check to the IRS each year. The idea is that if voters are really ticked off about taxes, they’ll want lower tax rates. So taxes need to be as salient and painful—i.e., as inefficient and distortionary—as possible.

Will is skeptical of this approach, though I would point out that the one major developed economy that doesn’t have withholding is Hong Kong. And that’s a place that has successfully constrained government spending.

To be sure, the spending restraint could exist for other reasons (such as the spending cap in Article 107 of the jurisdiction’s Basic Law), but the hypothesis that people will want less government if taxes are painful is quite reasonable.

And, by the way, requiring lump-sum payments rather than withholding wouldn’t change the degree to which taxes are distortionary.

Will then turns his attention to the ‘supply-side” argument about lower tax rates.

Supply-siders generally present two scenarios, and neither helps reduce the size of government. One: If the tax cuts pushed by ticked-off taxpayers create supply-side stimulus and increase rather than decrease revenue, there’s no downward pressure on spending. …But it doesn’t make government smaller. Two: If tax cuts aren’t self-funding and simply leave a hole in the budget, the beast (as Niskanen showed) does not therefore get starved. Instead, spending feels cheap, the beast grows even more, and the tax bill gets shifted to the future.

Since I’ve already addressed the starve-the-beast issue, I’ll simply note that self-financing tax cuts (which do exist, though only in rare cases) are only possible if there’s a big uptick in growth and/or compliance. And to the extent that the revenue feedback is due to growth, that will mean that the burden of government spending will fall relative to the size of the private sector even if actual outlays stay the same.

Maybe I’m insufficiently libertarian, but I’ll take that outcome every day of the week. Heck, I’m willing to let the government get bigger so long as the private sector gets to grow at a faster pace.

Now we get to Will’s main point. He suggests that maybe libertarians shouldn’t be so fixated on the size of government.

…well-funded and well-organized attempts “to convince voters to reduce their demand for the services financed by federal spending” so far have all failed. It’s time to consider the possibility that there’s no convincing them. …If we look at the world, what we see is that when people get richer, they want more welfare state. Maybe there’s nothing much we can do about that. …When people get richer, they want more welfare state. You can want Americans to get continuously wealthier and also want the government to consume a smaller share of national economic output, but there’s very little reason to think you can have both of those things. That is what the world is telling us.

To the extent that Will is simply making a prediction about the likelihood of continued government expansion, I assume (and fear) he’s right.

But to the degree he’s arguing that we should meekly acquiesce to that outcome, then I’ll strongly disagree. I may lose the fight against big government, but I intend to go down swinging.

Interestingly, Will and I may not actually disagree. This passage points out that it’s a good idea to fight against ineffective programs and to support entitlement reform.

…accepting that it’s probably not possible to shrink government would have a transformative effect on right-leaning politics. We would focus on figuring out the best ways to match receipts to outlays… You start to accept that spending cuts are ultimately more about optimizing the composition and effectiveness of spending than about the overall level of spending or its rate of growth. This doesn’t mean not fighting like hell to slash nonsense programs, or not prioritizing reforms to make entitlement programs fiscally sustainable, or not trying to balance budgets from the spending side, or not trying to minimize the rate of spending growth. This just means that you do it all knowing that the rate of spending growth isn’t going to go negative unless you hit a recession, a debt crisis, or end a major war.

And, most important, this passage also highlights the desirability of a policy to “minimize the rate of spending growth.”

Gee, I think I know someone who relentlessly argues in favor of that approach.  Indeed, this guy is so fixated on that policy that he even created a “Rule” to give the concept more attention.

Indeed, this guy is so fixated on that policy that he even created a “Rule” to give the concept more attention.

I can’t remember his name right now, but I’m sure he’s a swell guy.

More seriously (and to echo the point I made above), it would be a libertarian victory to have government grow slower than the productive sector of the economy. To be sure, obeying my rule (which actually does happen every so often) doesn’t mean we’ll soon reach the libertarian Nirvana of the “night watchman” state set forth in the Constitution.

But the real fiscal fight in America is whether government is becoming a bigger burden, relative to the private economy, or whether its growth is being constrained so that it’s becoming a smaller burden.

Will closes with a very sensible point about not overlooking the other policy areas where government is hindering prosperity (though that doesn’t require us to give up on the very practical quest to limit the growth of government).

Giving up on the quixotic quest to…falsify Wagner’s Law would also lead us to…focus our energy on removing regulatory barriers to economic participation, innovation, and growth.

And his concluding passage is correct, but too pessimistic.

This is just a conjecture. But when…the United States—where the freedom-as-small-government philosophy is most powerfully promoted and most widely accepted—has lost ground in economic freedom year after year for nearly two decades, it’s a conjecture worth taking very seriously.

Yes, he’s right that overall economic freedom has declined during the Bush-Obama years.

But what about the fact that overall economic freedom increased during the Reagan–Clinton years? And what about the fact that we achieved a five-year nominal spending freeze even with Obama in the White House?

In other words, there’s no need to throw in the towel. I may not be overflowing with optimism about whether we ultimately succeed in sufficiently constraining the growth of government, but I feel very confident that it’s a worthwhile fight.

P.S. While I disagree with a few of Will’s points, I think his article is very worthwhile. Moreover, a consensus on restraining the growth of government would be an excellent outcome to the debate he has triggered.

But I can’t resist being a bit more critical about something Noah Smith wrote about Will’s article. In his Bloomberg column discussing the hypothesis that libertarians should focus less on (or perhaps even give up on) the battle against government spending, he has a passage that is designed to lure readers into thinking that small government is associated with economic deprivation.

…a stark fact — the richer a country is, the more its government tends to spend. …Today, the top spenders include countries such as France, Denmark and Finland, while the small-government ranks include Sudan, Nigeria and Bangladesh.

Sigh.

It’s true that the burden of government spending is much higher in France, Denmark, and Finland than in Sudan, Nigeria, and Bangladesh, but let’s take a look at the overall data from Economic Freedom of the World.

France (#57), Denmark (#21), and Finland (#20) are all much more market-oriented than Sudan (unrated, but would have an awful score), Nigeria (#113), and Bangladesh (#121). Smith’s argument is akin to me saying that government-built roads cause economic misery because that’s how they do it in the hellhole of North Korea.

More important, he either ignores or is unaware of the research showing that nations such as France, Denmark, and Finland became rich when government spending was very small. Sigh, again.